A personal investigation of object and artifact and its role in connecting to home and place.

There is a point to a design practice, when I think we all establish a boundary of how much we share of ourselves and our lives. Yet it is those very experiences, the ones where we become vulnerable to life, that make us strong designers. Whether that vulnerability it is to others, to ourselves, or to the ethereal workings of thought, that openness gives ways to a greater understanding of the world around us.

My brother has long suffered with addiction and mental health issues, and during an attempted visit at the beginning of this year, I ended up needing to take him the the hospital. This was his second time he needed hospitalization in three days. I witnessed active prejudice and stigma against him, and the treatment he received was rough and un-compassionate. I wasn’t able to gain access as a visitor, was having a difficult time getting information from staff, and was trying to find a way to bring him some peace and get him to stay where he was safe.

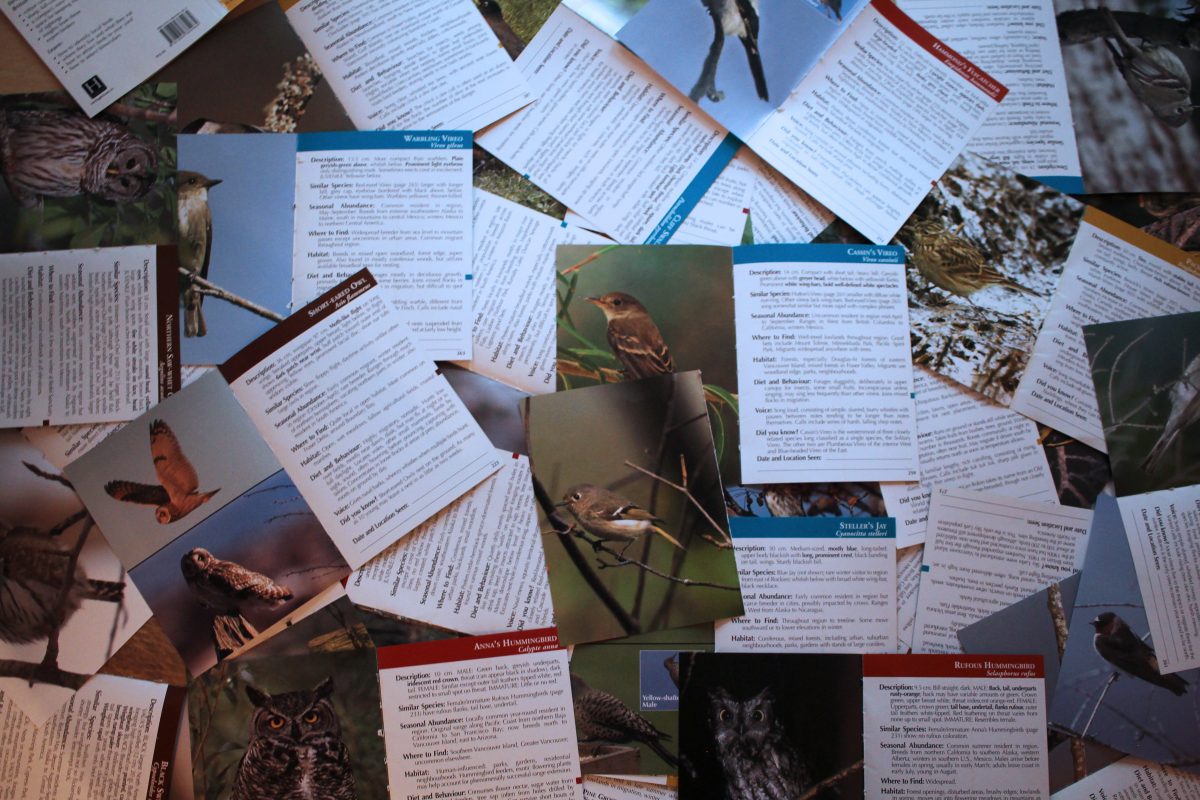

My brother is an avid bird-watcher and so I thought that bringing him a book of birds would ease some of his anxiety and he would also know I was thinking of him. Sadly, they never gave him the book and he was later transferred to a hospital in Victoria without informing me. I took the book back from the hospital, now with a stamp of the stigma and poor treatment of a vulnerable person I loved. My attempt of a small comfort was now labeled “patient transferred, unknown sender” in a brown paper bag.

I returned to my studio and began to dismantle the book. Carefully, deliberately removing bindings and glue, I took each page apart until I was surrounded by sheets of birds. The act of dismantling to begin again with something new, to redefine the object, and to exert some energy and emotions.

I began to fold the pages into birds, initially as an act of helplessness, then meditation, and as time went on, a series of small blessings for my brother to find his way home safely. The act of making became a form of healing and processing my emotions. It was a form of communication both to myself and to my brother.

I was reminded of the pigeons I used to watch from my balcony in Sweden. Grey iridescence, they moved through the sky, circling back and forth, back and forth until the found their way home. In a situation that felt out of my hands, each little pigeon I folded became a blessing for my brother, sick and lost within himself, to find his own way too.

It was within this act of making, these small transformations of shapes before me, that I began to realize that in my attempt to connect artifact to home, I had begun a conversation with the materials before me. That the act of making had become multifaceted. It had become an act of meditation, of conjuring up past memories, and as a way to connect both to myself and to my brother. There was a heightened significance to my material, and this connection, this communication was what gave this act meaning.

What began as an investigation of object and artifact and its role in connecting to home and place gradually developed into something much more. As a designer and artist, I took the act of something painful and personal and put my energy into the materials and act of making. It became a source of healing. By placing significance on the object and the act of care that was deemed insignificant by the healthcare system, I was able to process some pain and helplessness that I felt in the experience of being a sibling of someone with addiction navigating help and support.