broom / brooms

With this next project, I wanted to continue to explore the power of place based materials in their local communities. An idea I had was to reach out to all of my peers who had recently relocated to Vancouver. I wanted to make them something of consequence — something that came from this land, and something that was special to them.

I sent out a google form to those nine individuals with a couple of simple questions:

<<Please list three objects / tools that are the most valuable or important to you in your home? (For example: something you use to prepare food or to clean with — something you use every day or that you would use everyday if you had it. please no electronics! thanks!)>>

and

<<Is there anything from the above list that you had at your last home but did not come with you to Canada? Something that you find you are missing?>>

I assured them a surprise for their participation (sorry guys, it’s coming I promise), and anxiously awaited their responses. In hindsight, it was a bit presumptuous to assume that nine unique actors would provide me with one single object I could fabricate to accommodate them all. Through conversations with mentorship and peers, it became clear that I needed to reevaluate my approach. If I wanted to provide an offering of place, to hopefully provide a caring gesture in that spirit, I would have to decide for myself what the appropriate choice object would be.

I thought making a piece of pottery, or possibly something carved by hand from wood, but did not feel that was quite right. I found myself on one of the Gulf Islands for reading week and was reminded of an old foe of mine — scotch broom.

“Scotch broom is an invasive woody shrub. It was first introduced to southern Vancouver Island in the 1850’s, and now grows prolifically throughout southwestern British Columbia. Broom is most often found in open areas such as meadows, forest clearings, roadsides and hydro corridors.

Broom changes the chemistry of the soil around it so that other plants can’t grow there. It spreads and grows quickly, creating dense monocultures. Broom is a particularly serious threat to the biodiversity of the Gulf Islands, eliminating native plant communities that birds, butterflies and othe ranimals rely on for habitat. Broom is also particularly flammable, increasing the fire hazard of a property.”

“Scotch broom is an invasive woody shrub. It was first introduced to southern Vancouver Island in the 1850’s, and now grows prolifically throughout southwestern British Columbia. Broom is most often found in open areas such as meadows, forest clearings, roadsides and hydro corridors.

Broom changes the chemistry of the soil around it so that other plants can’t grow there. It spreads and grows quickly, creating dense monocultures. Broom is a particularly serious threat to the biodiversity of the Gulf Islands, eliminating native plant communities that birds, butterflies and other animals rely on for habitat. Broom is also particularly flammable, increasing the fire hazard of a property.”

– Islands Trust Conservancy Website, British Columbia

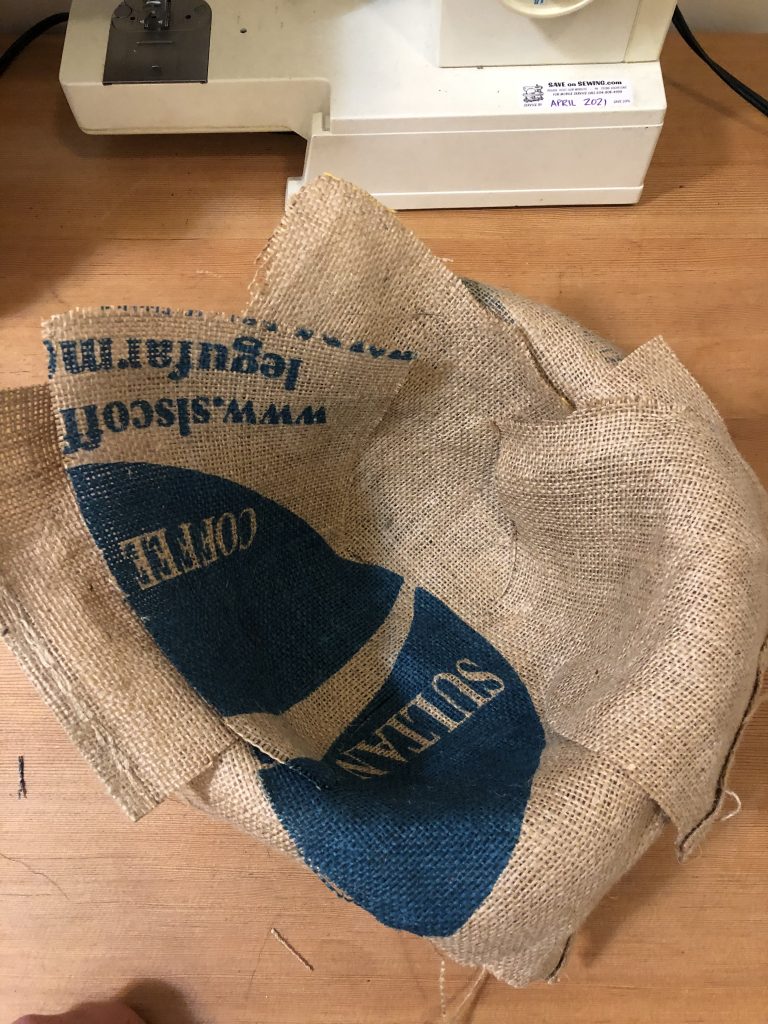

This spindly, opportunistic invasive plant is everywhere on the Gulf Islands. It was brought over with the European colonizers to these lands because of its quite lovely yellow blossoms; however it has seeded itself uncontrollably on this land, along with many other invasive plant species. Scotch broom’s namesake comes from a traditional use for the plant (or so I’ve read) as a material for broom making. I’ve been curious to try this for myself, and was glad to have another reason to clear out some of the broom from the orchard on Piers Island, so we collected several branches to begin drying them out for the experiment.

Scotch broom hanging to dry, top right

Shortly after, we received an email that the Piers Island Invasive Species Committee was having a Valentine’s themed invasive species removal party! What luck! We threw on some thick garden gloves, grabbed the big clippers, and headed back to the orchard to really tackle it. Over the years, tree skirts have been cleared to open up the communal spaces to light and grass, leaving way for gorse and broom to fill in. They are so established in parts of the island that they have to yearly remove the plants, and burn the roots, only to have to repeat again annually. They are too aggressive to be eliminated entirely, maintenance of the problem is the best that can be done, otherwise they will claim all unshaded open land.

removing the invasive species party!

gorse and broom in the field

burn pile of mostly gorse and scotch broom

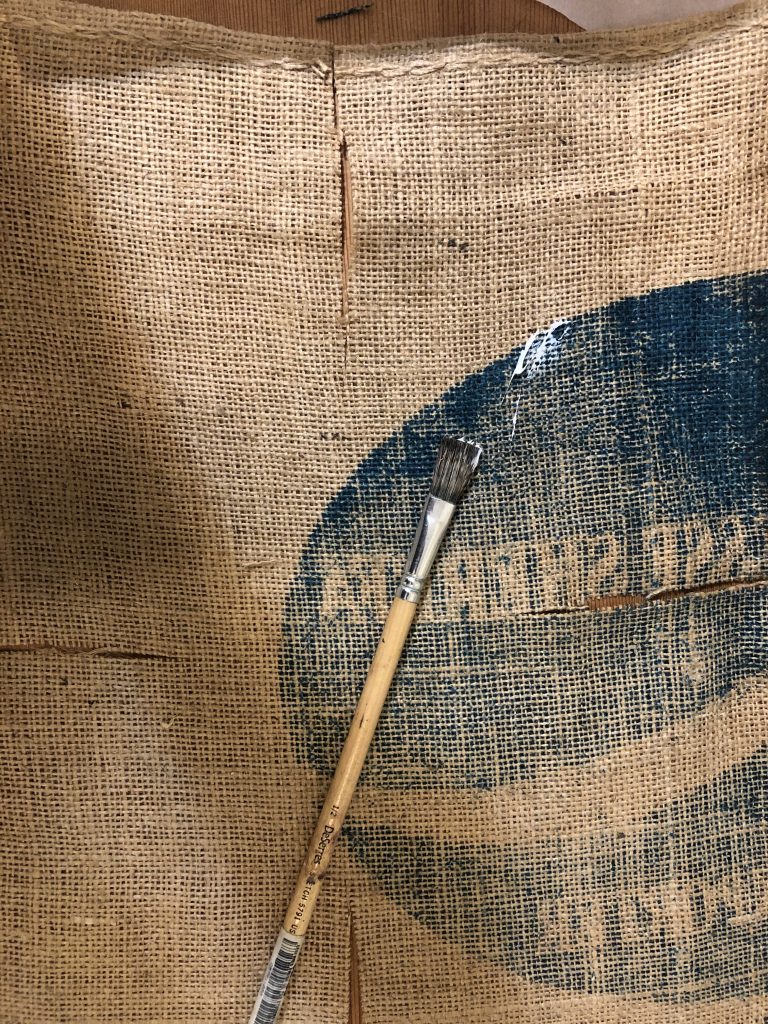

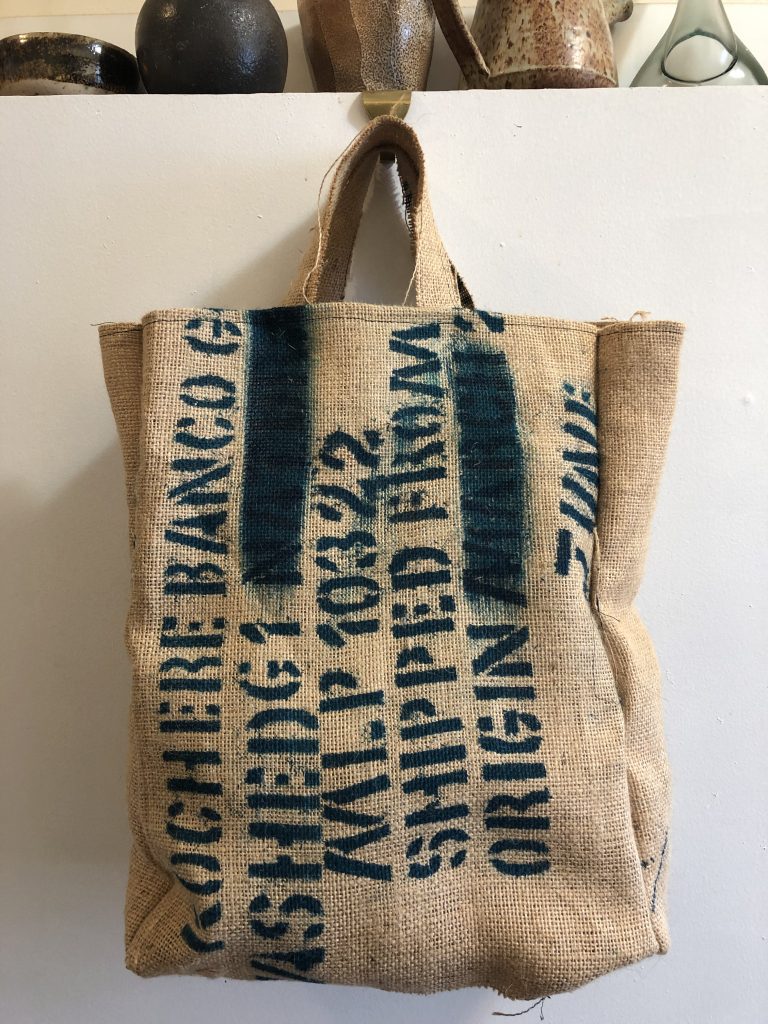

Talking to the organizer of the event, Charlotte, a full-time resident on the island, it came up that I was interested in exploring the opportunities to use invasive plants as a material in my practice. Immediately she began to suggest that I sell the brooms in the Piers Island Gallery (known colloquially as the PIG) and offered that it would be great to offer the brooms as an example to fellow islanders of the potentials of the material and an incentive to remove it.

This conversation struck a chord, as I realized the potential of such a project on such a small community of Piers Island. It’s a good place to start such a relational exercise, especially since that particular place means so much to me as I continue to deepen my relationships with its residents, traditions, and natural beauty.

Pulling and cutting away at the blackberry, scotch broom, and gorse (the latter being undoubtedly the most aggressively thorny of the bunch), I began to think of how pulling invasive species that were brought over amidst colonialism was akin to pulling out it’s continued spread on the native landscapes that remain (somewhat) untouched. It’s a satisfying mantra when you’re knee deep in thorns with a sore back. Also the towering burn pile of plants at the end of the day, along with coffee and chocolates, made it a satisfying exercise in more ways than one.

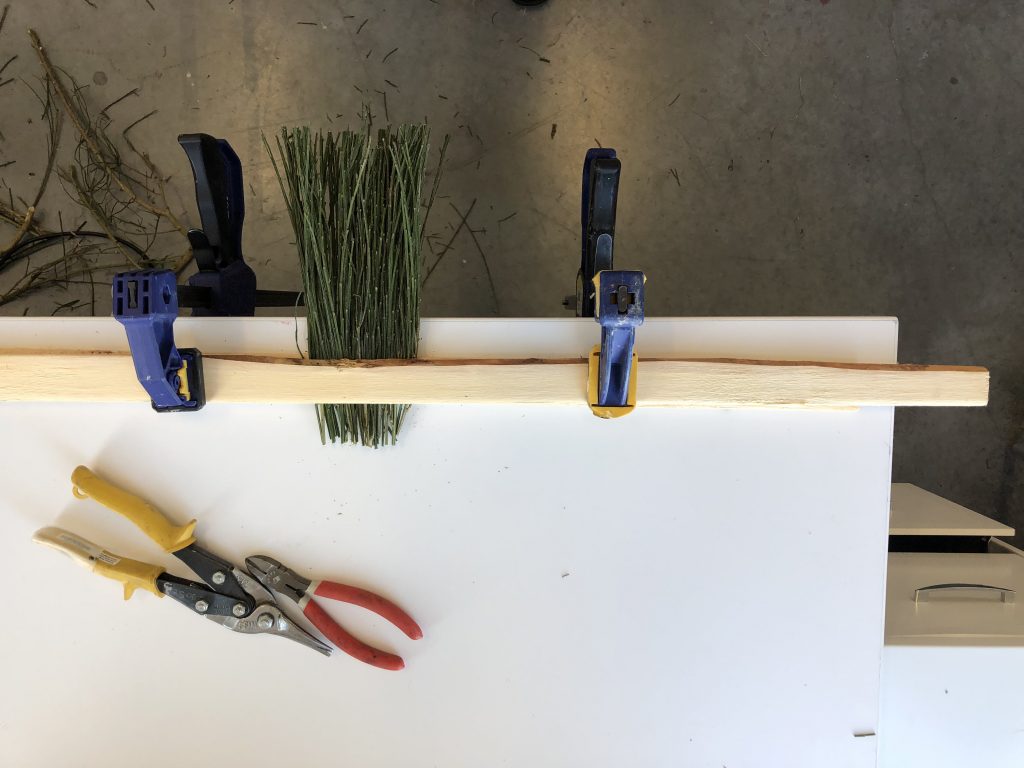

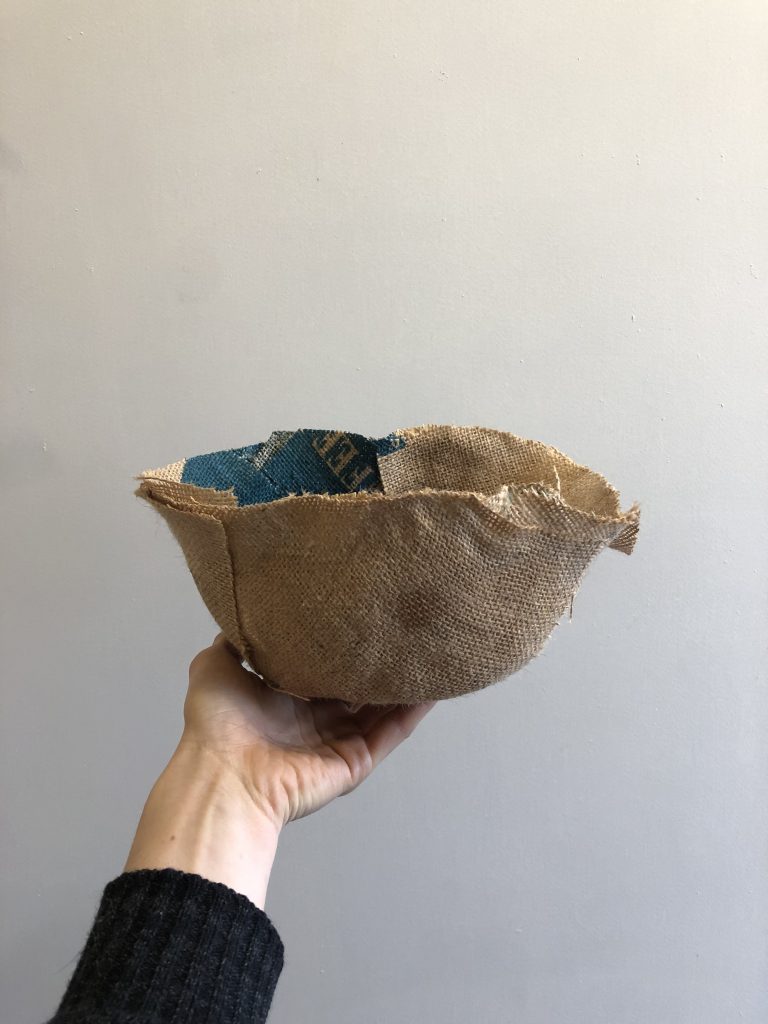

I made a prototype of a broom before it had dried with cotton string, just to see how it would go. Though a crude representation of what I hoped to create, I was happy with the potential.

The broom is taking much longer to dry out completely, so I’ve had to make the first half with still green material. I’m going to wait on the rest until it is brown and dry, to compare the pliability and difference in resistance. I’m looking forward to seeing how that goes!

This experience went a different way than I planned, but I am eager to make more brooms, keep up the relationships with the islanders, and the conversations about place based materials. Particularly with communities who recognize how those materials can serve a greater service to the land and it’s inhabitants.