For project 1 semester 2, I conducted a workshop in the second week of the class, Transformative Storytelling for Social Justice. I sent out the following prompt the week before class to prepare for the workshop:

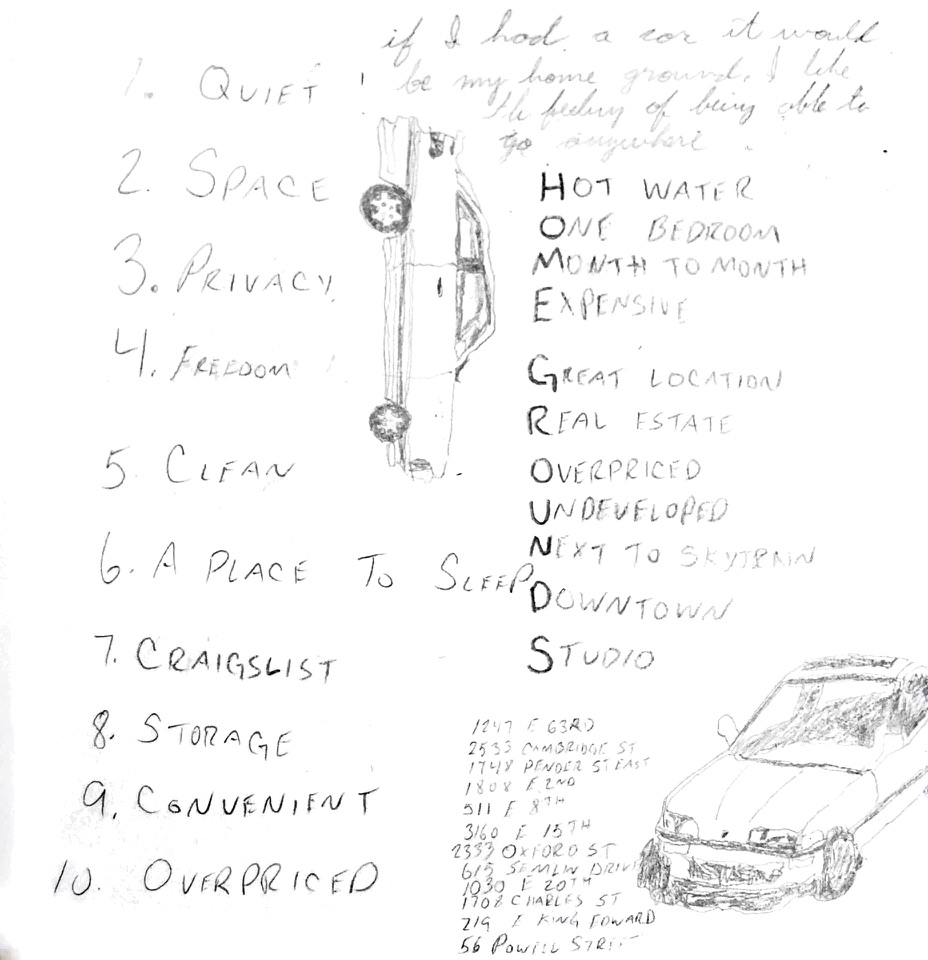

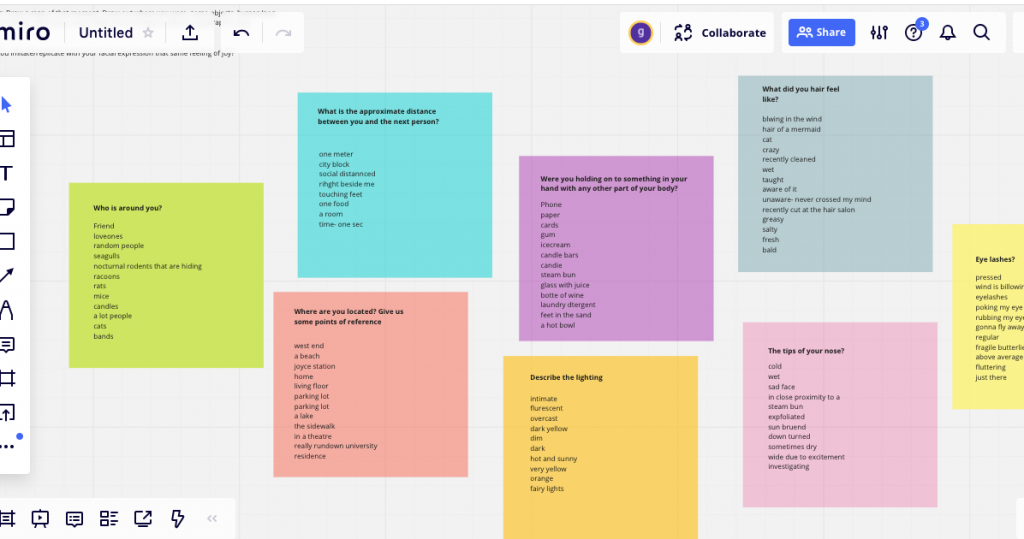

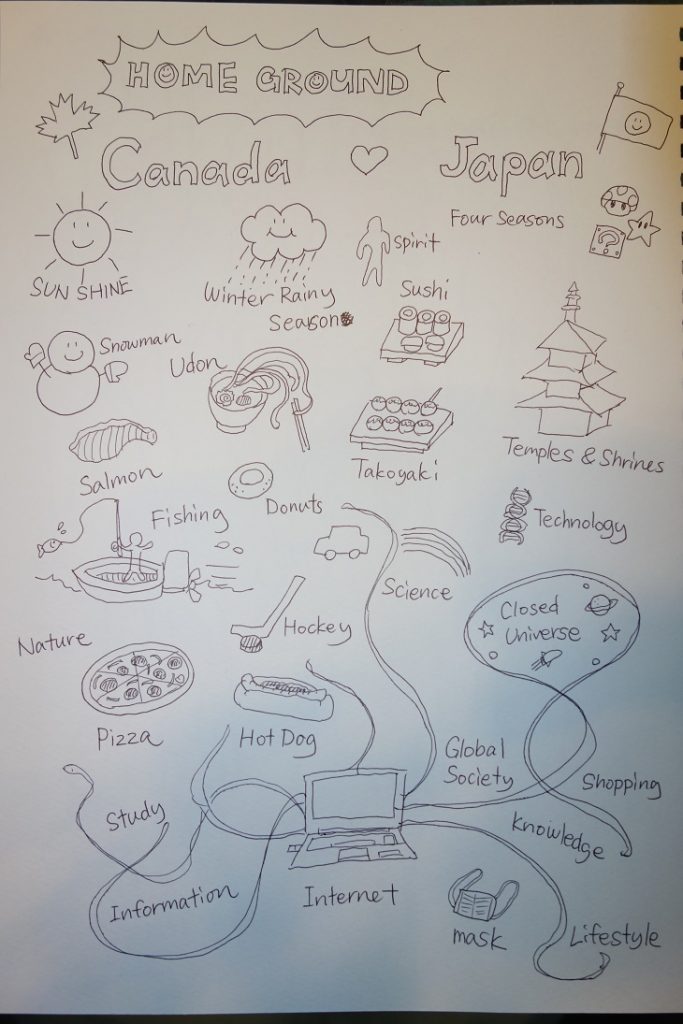

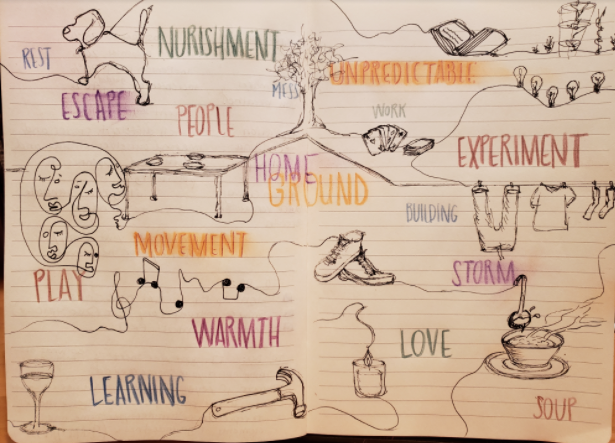

“Next week we will come together to think about our home grounds, where we come from and the way in which we bring our unique experience to collective gathering and sharing spaces. We will inquire together how we carve space for our own voices and make room for other diverse and divergent ways of knowing and being. For now, for this weekend, I’d like you to think about what makes your “home ground”, whatever that means to you. Think of 10 keywords. Write them out on a piece of paper. Fill that page up with doodles and marks to represent or consider your home and elements of groundedness. There is no right way to do this. There is certainly no right interpretation of home ground. Looking forward to talking more about this next week!”

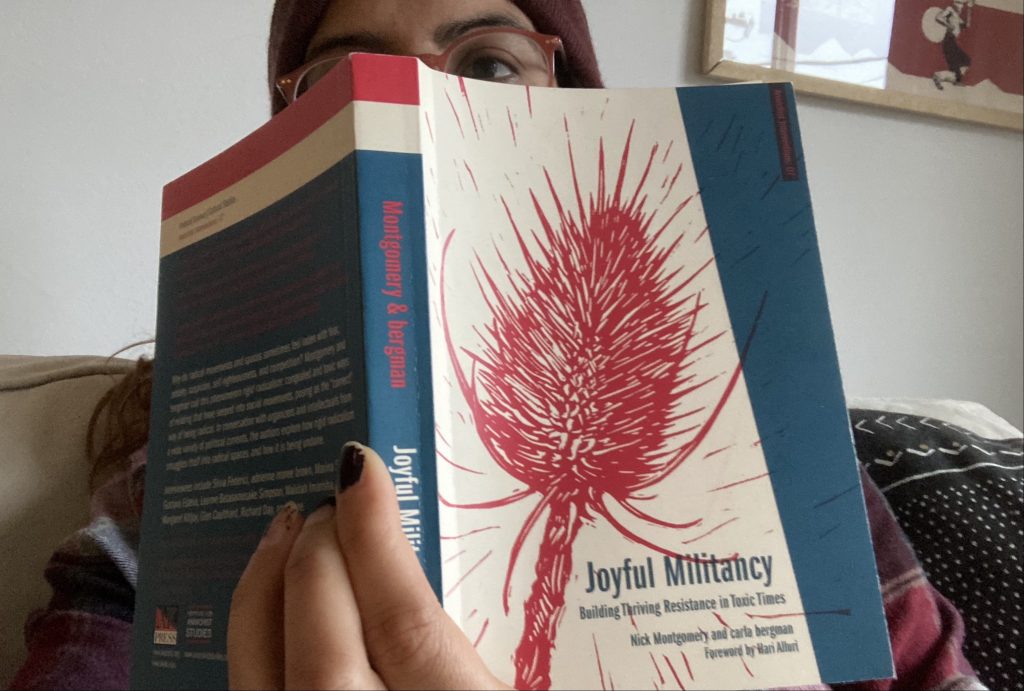

I formulated the workshop as an extension of the last couple of exploration from last semester and guided by the book, Joyful Militancy and Judith Butler’s writing on performativity.

Transportive exercise to set the mood

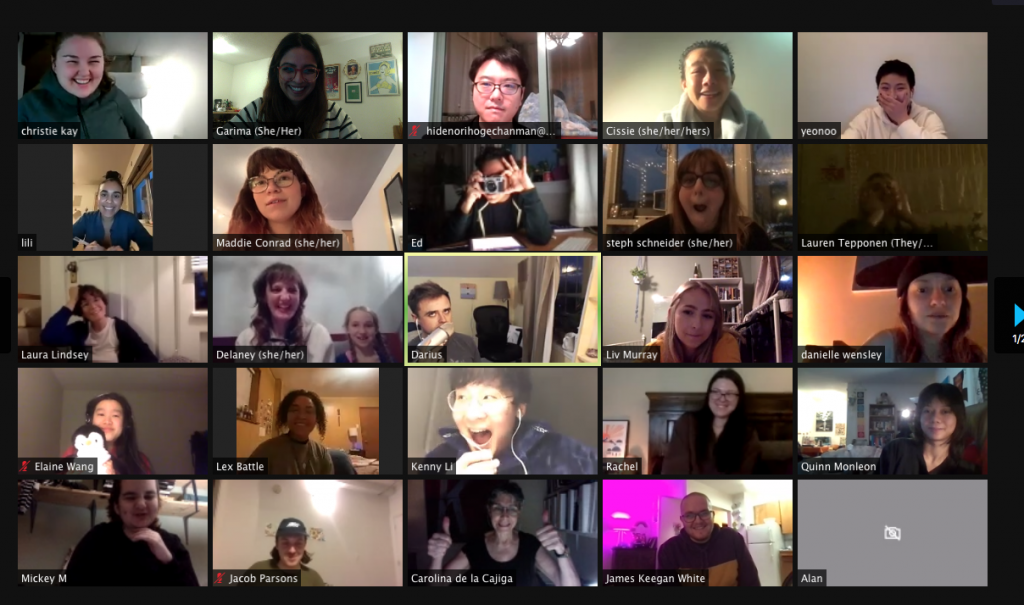

I started the workshop with Joy activity that I had tried with the studio class last semester. The Joy exercise transports people to a place of joy, setting the stage for the subsequent activities. Joy as a methodology is mentioned in both Pleasure Acitivism and Joyful Militatncy. Both books refer to Audre Lorde’s description of the erotic as a synonym for joy. According to Lorde, the erotic is “ a grave responsibility projected from within each of us, not to settle for the convenient, the shoddy, the conventionally expected nor the merely safe.” Joy is also the capacity to be fully present in the moment and with ourselves (Montgomery and bergman). Joy also comes from fostering affinities and relationships which lends to forming, per-forming collectives. It felt to important to start a class on social justice in a way that centred joy as a practice and collective performance to be able to take on the heaviness of the engagement to follow.

Part II- Cartography Workshop

The trajectory of the workshop

- moves people inwards first,

- then outward to invite people in,

- then to move outward together.

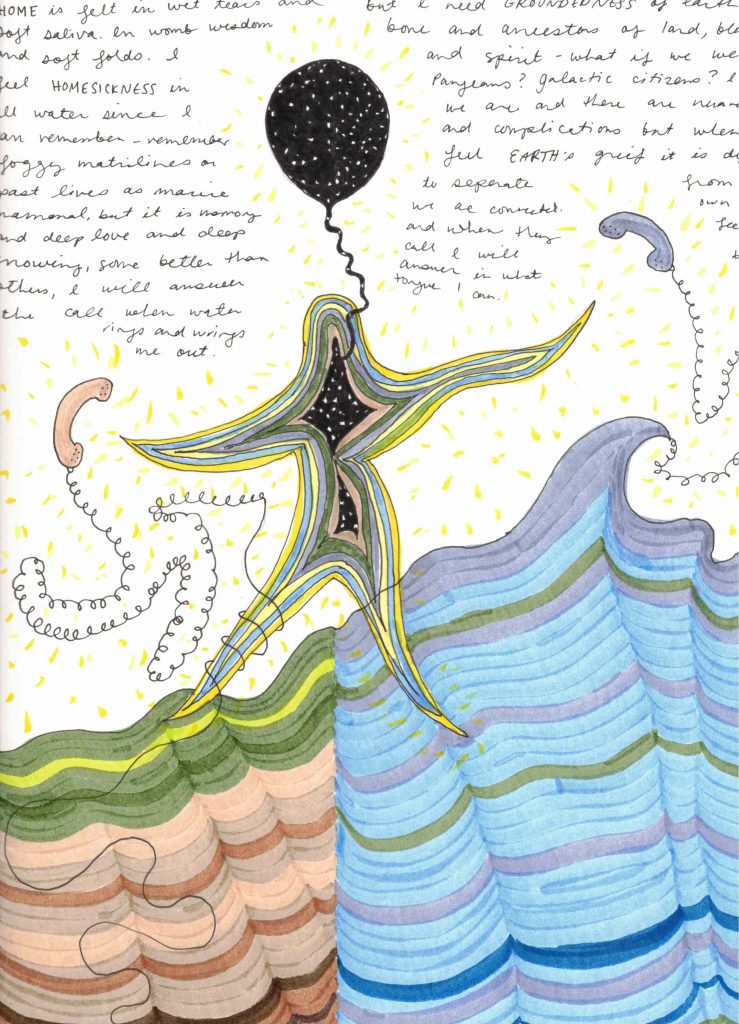

The cartography workshop was designed to explore the role of performativity in how we share individual identities and build collective ones. The guiding question for the workshop sought to inquire how we define our home ground, that is to recognize those elements in our lives that make us feel a sense of belonging, rootedness and groundedness. The importance of this question rests in the assumption that to be open to diverse opinions, we must first feel at rest with our own sense of self and identification to groundedess or home.

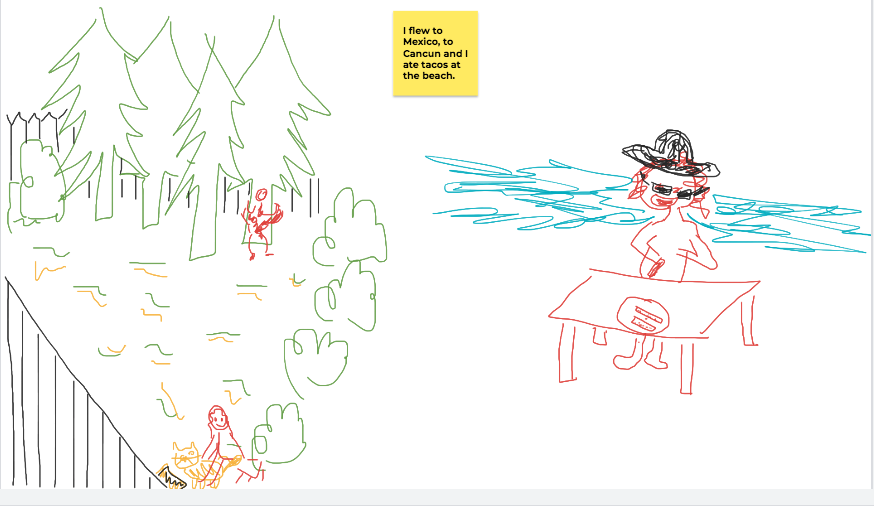

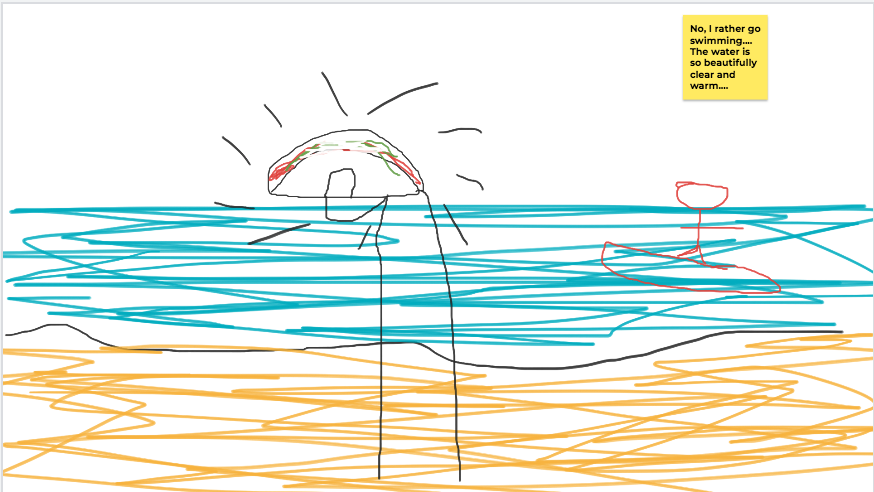

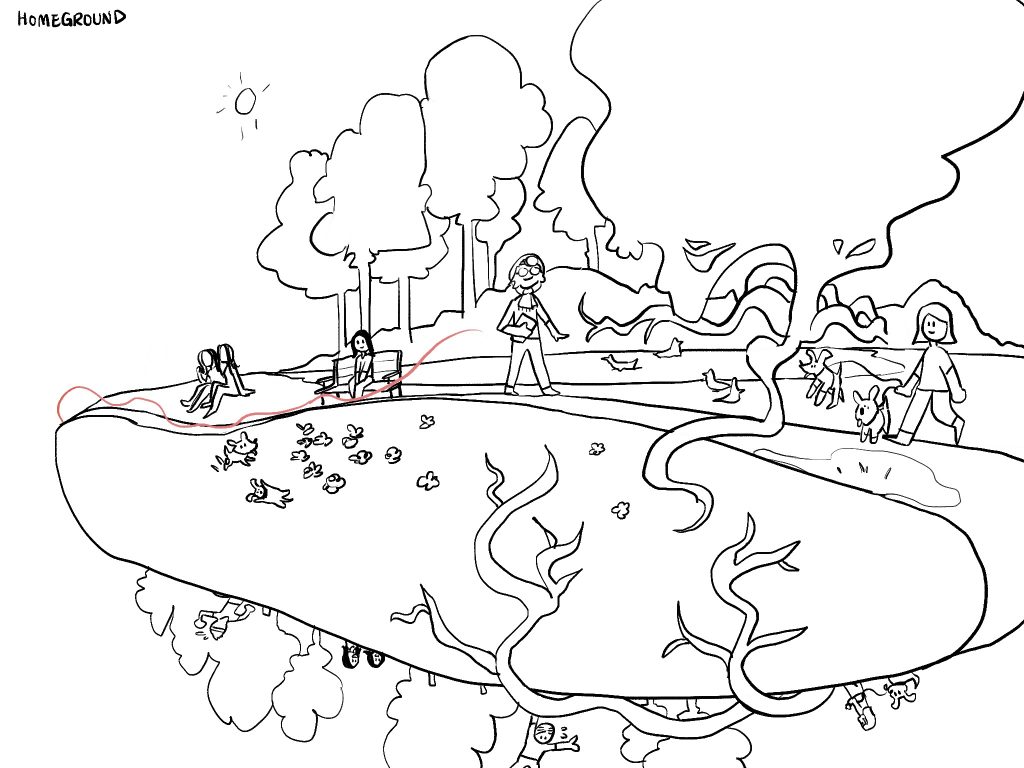

People were asked to describe their home ground to a group of 3 people. The listeners were prompted to draw the narrator’s home ground while it was being described. The narrator would then ask the listeners to jump to the narrator’s home ground, drawing themselves and describing what they are doing in this new place. Here a performance begins through which all the participants move through each other’s home grounds imagining, empathizing with each other’s personal narrative and space. In the last part of this exercise, the participants connect all the homeground stories together by travelling as a collective from one homeground to the others bridged with threads of imagined and performed narratives.

Construction of identity- performing the personal with the collective

As they created the second narrative through which the listeners were invited into the narrator’s home ground as well as the third narrative that brought all the stories together, a performativity became evident.

To describe performativity, performing subjects according to Judith Butler are “involved in a movement of continuous construction and reconstruction of their identity, that relies on internal mechanisms as much as on relationship with others, with the social and intersubjective dimension, in terms of gender, race, culture, and so on. (Dalmaso, 2018)”. I witnessed moments when participants were placing themselves in other’s stories by imagining where they fit in. The were situating themselves in this imaginary place, finding spaces where their identities aligned with others as well as stretching to an extent those pre-constructed boundaries of comfort that would otherwise keep their identities bound. One listener clearly felt comfortable at a narrator’s backyard as they spent a lot of time in their own backyard planting their garden. Another participant had never hitchhiked before but in this imaginary exercise he was keen on performing with the other as a wandering hitchhiker.

In the context of social justice within which this workshop was hosted, performativity, particularly collective performativity can be perceived as a political act. Butler recognizes that acting collectively on the one hand displaces people in a way – our identities become interconnected with those of others by which we relinquish parts of our own identities (Soderback 2018). Meanwhile, in Dalmaso’s interpretation of Judith Butler’s notion of performativity, “performativity is understood as the power to virtually engender the conditions of its own political action, and, through this very process, start to realize it (Dalmaso, 2018)”. Grounded in Butler’s notion of performaitivity, this activity facilitated a performance of collectively moving through home ground stories as way to engender and realize a pluriversal collectivity, which in my opinion is a political act.

I found Butler’s words emerging in the collective performance that took place in this activity that brought together people from all different backgrounds and geographic locations:

“Obligations to those who are far away, as well as to those who are proximate, cross linguistic and national boundaries and are only possible by virtue of visual or linguistic translations, which include temporal and spatial dislocations,” Butler writes.35 To approach the other in their alterity, and to summon a sense of solidarity that compels us to act across differences, we have to disrupt and displace our own spatiotemporal orientation, which is to say that we have to “lean out,” dislodging ourselves in a mode of ec-statis and exposure. This requires “being at once both there and here, and, [End Page 36] in different ways, accepting and negotiating the multilocality and cross temporality of ethical connections we might rightly call global.”36– Butler

Absurd and Humorous Performances to fabricate plural realities

Some of the collective stories made up in the workshop breakout rooms stood out to me for their absurd and humorous narrative arcs. It made me think of the following conversation:

Words from the Keep it in the Ground (at the Indigenous Environmental Network ), Dallas Goldooth who talks about the role of performativity and humour in activism.

“Put it in terms of theater: we’ve constructed these identities, these masks that we doent realize are fucking hilarious masks and whether it’s the…a mask of what is a man or a mask of what is an acitvist, an anarchist, radical or mask of a feminist– they’re all masks that when you start breaking it down, like, look, those are actually fabrications that are quite funny and absurd. Maybe not necessarily funny but absurd in ways. Its an absurd fabrication of our social conscience–we are fabricating our reality. And we can’t help but do that. It’s ingrained in who we are ’cause we’re self aware, and so, in the process of being self-aware, we create these…we’re fabricating these identities.( Pleasure Activism- The Power to Make Light, Adrienne Marie Brown in conversation with Dallas Goldtooth)

Home Ground Prep

1. scenery

2. foods

3. spirit

4. friends

5. internet

6. situation

7. color

8. weather

9. travel

10. birds

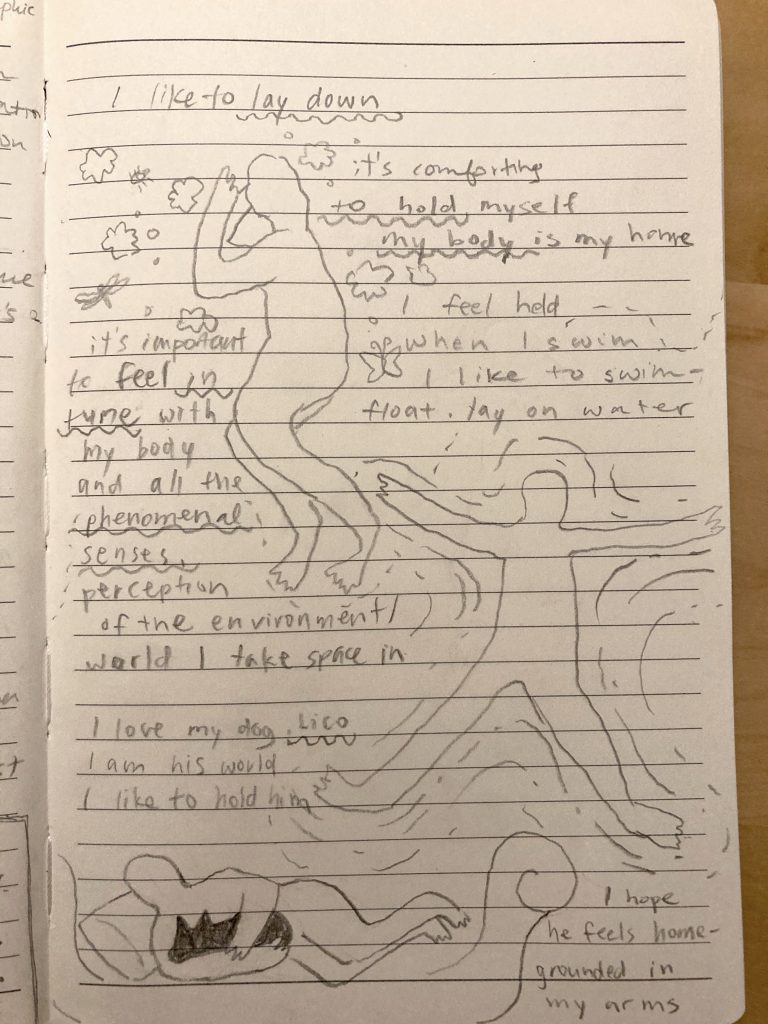

TS No way! having a sense of home in your body is really important. It is the one thing that should truly belong to you.

I also really love floating on top of the water. If you tilt your head back and your ears are under the water you can hear the movement of the whole body of water, it feels like you are connected to everything, supported by every molecule and moving/ swaying/ bobbing in tandem with all the matter that surrounds you.

My favourite local body of water to float in is Sasamat Lake. It gets really warm in the middle of summer and is just big enough that you can swim out the the middle of the lake without being too far from shore and when you lie back and look up all you can see is sky. In August last summer I went out with a friend and we swam out at around 8:30. The sunset made all the clouds the most beautiful mix of peach and orange and they were streaked all the way across the sky. This is a treasured memory for me.

Can we meet Lico in class sometime?

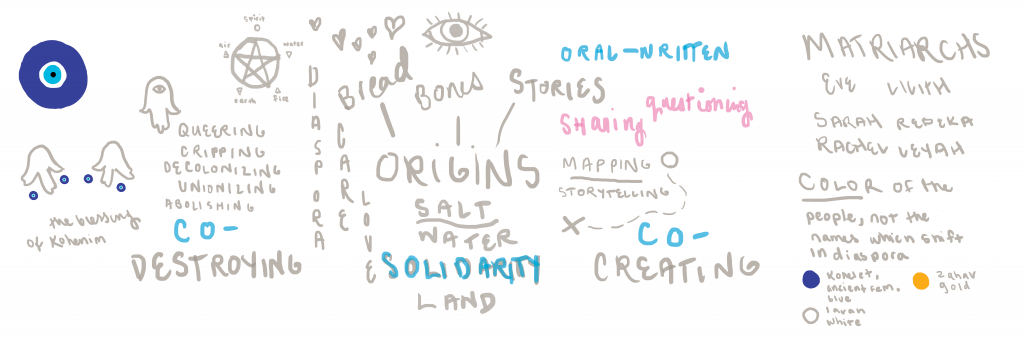

Being Jewish the nazar is super important and one of the few objects that in diaspora I still have connection to from my original/indigenous Homelands in SW Asia

for everyone’s reference, it is also the Goddex’s Eye (gender neutral term for God/Goddess) , which is what is being depicted in what is yes, the live long and prosper star trek gesture because Leonard Nemoy is a big ol’ Jew and is a Kohen like me. Kohenim are high priests from a tribe of priests (not like christian priests) and that oversee some of the big spiritual and ritual stuff including a yearly blessing for the new year where the idea is essentially this:

Everyone is in synagogue, or wherever they worship for the holiday

Kohenim go to another room with water and wash hands with a blessing

Kohenim come back into the room with all the people, and non-Kohenim close their eyes in preparation for the blessing of/by/through the kohenim

Then the Kohehim go in front of the people raise their hands in that gesture toward people and Goddex looks and blesses the people by just peeking through the fingers of the Kohenim, which makes 4 Goddex eyes/nazarim per person. All this is meshugas is because if people look directly at Them or vice versa they may turn to ash or a pillar of salt or something

Then boom! the people are blessed

S- I recently made Ramen from scratch (except the noodles) and I followed this recipe! Except I made a kara-miso tare instead of the shio.

https://www.forevernomday.com/recipe/tonkotsu-shio-ramen-and-chashu-pork/

So good! It takes a lot of prep, especially if you cut and clean your own pigs feet instead of going to buy bones. But it’s so so worth it, and the bones last a few rounds. I froze them, and am using them for the second time around right now, and the tonkotsu broth is soo good. The Ajitama (marinated/pickled eggs) recipe here is good too.

M- HOME IS SOUP- (a poem)

coming together to make with whatever you can bring,

something that is made for sharing

provides sustenance

a way to put warmth into your centre

and that feeling when it spreads from your heart/stomach out to your fingertips??

Fuck!! it’s something ancient and visceral

HOME IS SOUP

WE MAKE SOUP

WE MAKE HOME

Carving Space

Carving Space

An important aspect of this workshop and a significant point of inquiry in my work is the notion of place-making and carving space. Soderback uses Arendt and Butler’s theories around space to describe space and location as a product not necessarily in physical or geographic location created through plural action, but through acting and speaking together. In this way, the cartography exercise became a semiotic representation of home and collectivity as well as an act of public place-making by way of acting and speaking together.

Drawing from Arendt’s notion of the public space of appearance as the scene of political action,15 Butler writes that “space and location are created through plural action.”16 In The Human Condition (1958), Arendt asserts that the true space of the Greek polis is not “its physical location”—it rather “arises out of acting and speaking together.” (Soderback, 2018)

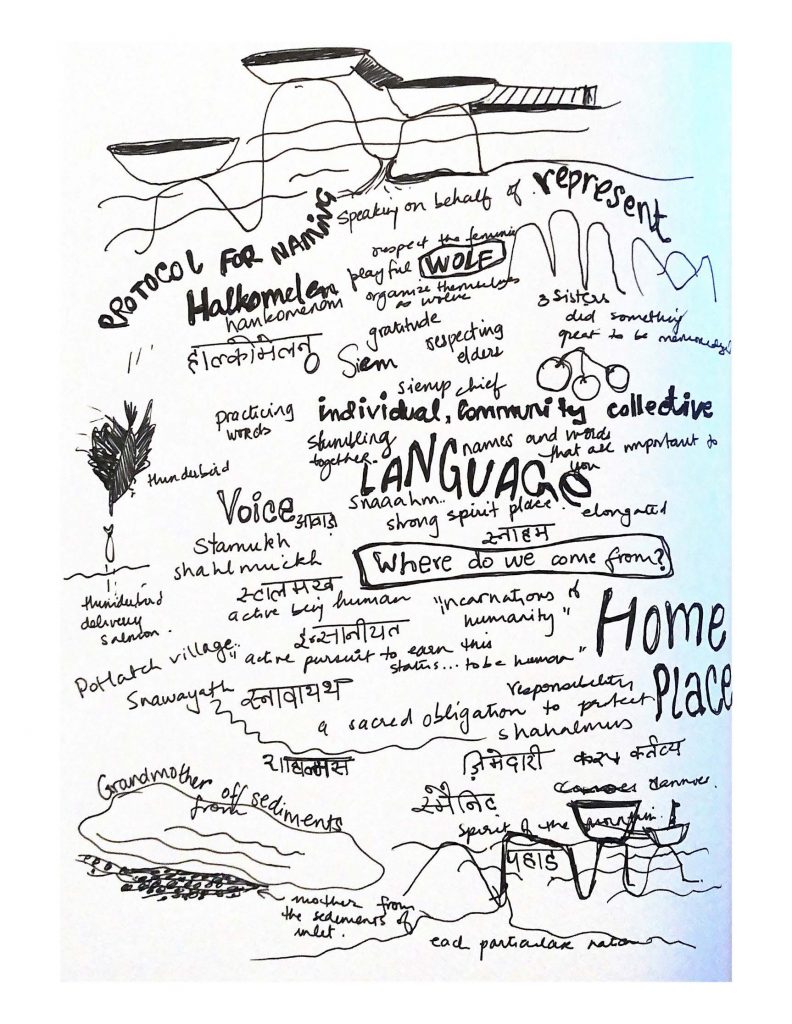

Indigenous ways of connecting to home- Home as responsibility

Notion of responsibility permeated throughout the workshop . I started the joy workshop with Audre Lorde’s definition of the erotic as joy. This definition speaks of joy as a form of responsibility which is also important to indigenous notions of self- identity and place. Keeping in mind all these incredible interpretation of joy, identity, home and place that are all grounded in responsibility I attended the first Place-Based Responsibility Roundtable discussion organized by the DESIS Lab.

The event, Language of Place took place a week after the home ground activity that I had facilitated. I attempted to use the same techniques of actively listening to another’s notion of home and place and connecting it to my own. Language and origin stories were two significant ways in which the guests connected to their home, identities and ancestral lineage. While listening, I had an intuitive urge to write the words spoken in Halkomelen in Hindi. It was a strained attempt at remembering how to write in Hindi- first a practice in phonetic translation. I then tried to think of words in Hindi that best represented the words. This was also hard- my Hindi isnt great! Example, Shahalmus (Halkomelen), sacred obligation to protect is Zimedari (Hindi)- an obligatory responsibility or Kartavya (Hindi)- a sense of duty maybe?

What stood out was the importance of being connected to home- one’s own sense of groundedness, an origin story perhaps, or a place where one is always welcome whether a chimera or a geospatial space that holds up the feet. This longing for home is best described by Wilson and Nelson-Moody:

“For as far back as we can remember, whenever we travelled the ocean or the bush, our teachers would often instruct us to ‘look back’. The way finding technique struck the dual function of maintaining forward navigational progress, as well as remembering our way back home, where home is more than just a place, but a responsibility to bring forth our love, joy and abundance.”