Colloquies on Iquebi’s tembiasakué

The project is written partially in Guarani and English. The Guarani language brings in my own cultural identity. It takes me to a place of introspection. It speaks to me of a different way of seeing and naming. It also gives me a safe space where I can go and reflect on my diaspora, on the borderlands that still hurt me.

There is a Lexicon at the end of the Post.

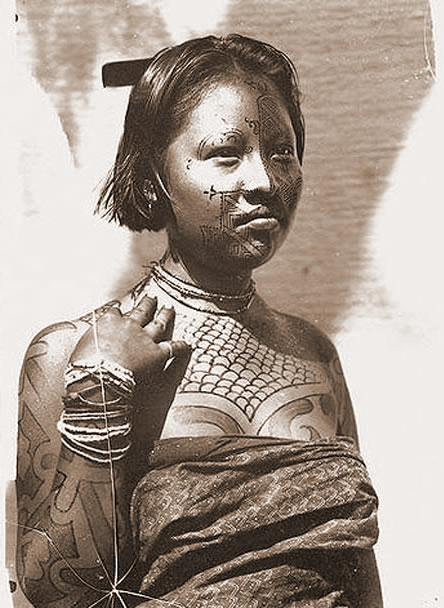

This is Iquebí’s tembiasakue (story), Ha’e (he is) an ayoreo-paraguayan indigenous kuimba’e (man) that on a long journey back home, went through different paths of colonization and decolonization, of learning, unlearning and relearning. Iquebi is a wayfinder, a designer of possibilities.

Iquebi’s voice can be heard Today as a claim on identity, with kunu’u (love) and pride for his culture. It is a voice that also brings urgency and due for action. His Tetã (nation/culture) is being destroyed. Ayoreo’s territory has a ka’aguy (forest) that cries from its deepest roots and asks for getting back its ways, its soil and its people.

When Kuarahy rises there is a rera for hope. It is a new ara rory jerovia. Ara is made out of histories. Time of tekovekue. For those who had the chance to live and for those who lost it all. Amombe’úta ndéve ko ava tembiasakue.

“I remember that my dad said to me: “Iquebi, don’t go very far from us, you are still very young, and in the forest something bad might happen to you” (far from the camp)…I looked at my dad and my mom, and I went with my friend whom I never should see again.

We were already a bit far from my dad and my mom, and suddenly we found some traces we never had seen before, which we did not know. My colleague said we should follow them, and so we did.

That day, I remember very well, there was bright sunshine and it was not very cold. My friend and I were playing and laughing a lot. We, the Ayoreo, always laugh a lot about anything. Soon we heard something terrible, a great noise, and we did not know what it was. We were frightened and started to run, but I was very small and could not run very fast. And then four guys showed up, mounted on some beasts I had never seen before; we ran as fast as we could, my friend to one side and I to the other, and I don’t know where he went, but the four guys followed me on their horses. And when they reached me, one of them tried to shoot me with a pistol, but another one clutched his hand, and so he did not kill me, but they caught me by lasso, with a piola (before, I did not know what a piola was, but today I know). When they caught me with the piola I tried to escape again, I thought: I am Ayoreo, I am stronger than them; but I tried in vain.

[…] When we reached the Bahía Negra, they finally took off the piola, but it was not to let me free, nothing alike, it was to put me into a cage. That moment I tried again to escape, I thought I would make it, but I couldn’t… the cage was locked. They threw me into the cage in Bahía Negra, and thus they took me till the port of Asunción. I did not know anybody; I had never seen the things I saw. That cage where they locked me was very small, like one meter, and I could not stand up, but sometimes they took me out a little bit to relieve myself. They did not want that I peed or shit inside the cage, therefore they took me out, but I could not shit because I did not eat anything. I could pee, because I was only drinking water, and they took me out to pee inside the boat, down there, peeing into the water; and I also fell ill, I had a lot of head ache, the flue and I was coughing; stuff I never had and never felt in the forest” (Iquebí, 2012)

This happened in Paraguay in 1956.

Amarilla, Deisy. Captura del Ayoreo José Iquebi (Capture of the Ayoreo José Iquebi), 2012

In a series of poteī (4) colloquies. I listened to Deisy tell me Iquebí’s story. Then, as a listener -messenger, I retell the story to poapy (3) other women from different backgrounds. .Amombe’uta (I’ll tell you) the reflections, perspectives that ha’ekuera (they) presented and also the ñomongueta (dialogue) that raised.

Colloquy 1: Daisy and Iquebí

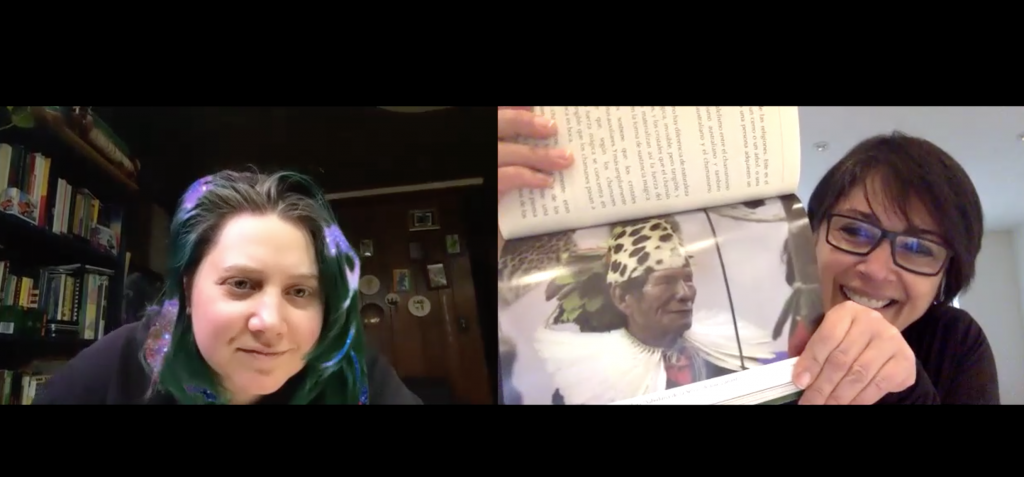

Dr. Daisy Amarilla is a Paraguayan anthropologist that for the past 25 years has been working with the Ayoreos. She is close friends with Iquebi and in 2012 she published a book about his life and the actual situation of the Ayoreos. She told me that there are only about 6,000 people now. That they still have a few families and groups that live in the forest without contact but that they don’t know for how much longer they will be able to do it so.

Most of them have to get out, because of deforestation and oil mining. Many live in settlements where they have been evangelized (by catholic and christian priests), alienated and subdued to the “modern” ways or colonization.

This is a story that unfortunately is not alien to most of indigenous cultures. We live similar stories of abuse, displacement, theft by governments and corporations in Canada and around the world. These stories need to be told. The only way to stop the abusers is to denounce and talk about the abuse. The only way that as designers we can decolonize is by creating space for decolonized places.

The decolonized design space is where we come to design with the world to let the world design us back (Anne Marie Willis, Ontological Designing, 2006). A space that confronts all our intersections and often transgresses our most intrinsic borderlands.

Ko ñombogueta Deisy ndive (this dialogue with Deisy) took us to reflect on the dire situation of the Ayoreos in their territory and in a need to change the way that education is being held. Today they have a generalized indigenous curriculum that in reality aims more to colonize and bring in the paraguayan government ways, neglecting indigenous history and culture. A sort of canadian residential schools replica, where the word “to modernize” is often repeated. Where capitalism prevails as the ruling in governments and institutions, compulsively displacing, racializing, discriminating in the name of progress or the public wellbeing.

Iquebi’s cage reminds me of how BIPOC people are seen in academic environments. How they are invited to “participate”, to talk about their realities, just to validate white privileged scholars, who hold tight to their positions of power. The rhetoric doesn’t change. It is like (for religious parishioners) going to mass to confess on Sundays, and then back to “sin” the next day. Inclusion is not giving equal space, It is not making room for having more diverse teachers and curriculum. “Moves to innocence” to keep white people upholding white people. (Tuck and Yang, Decolonization is not a metaphor, 2012).

“If we examine critically the traditional role of the university in the pursuit of truth and the sharing of knowledge and information, it is painfully clear that biases that uphold and maintain white supremacy, imperialism, sexism, and racism have distorted education so that it is no longer about the practice of freedom” (Bell Hooks, Teaching to transgress, 1994).

D. Amarilla just presented to the paraguayan senate a project to change the indigenous educational curriculum for the ayoreos, in order to include the teachings of their own history and culture by ayoreos teachers.

Colloquy 2 : Amombe’úta Marcia

Marcia Higuchi is a MDES in Interdisciplinary Design candidate at Emily Carr University. Marcia will soon become an immigrant in Canada. Marcia and I share a lot of similarities in the way our countries evolved. We lived dictatorships, recurrent corrupt governments and a modus vivendi that makes both our countries very much alike as “modern”colonial states. (we also share extended geographic borderlines).

For Marcia, Iquebi’s story took her to her own grandfather’s history who immigrated from Japan when he was 14 years old and that, as Marcia tells, had with him all of his life in Brazil, his love and yearn for his culture. We also reflected on language. How for both Iquebi and Marcia’s grandfather,knowing their language was a strong force that kept them connected to their cultures.

Language for me is a place of reflection, a refuge, a way back to my memories, my identity. It is also a breakpoint, to shift, to acknowledge my own self and all my intersections. I am a latinX, mestiza, immigrant in Canada, a “naturalized” citizen, a mother of Canadian children, a wife, a queer brown woman. Guarani, Spanish and English languages convert and divert, bounce and hold the words that shape me.

Colloquy 3 : Amombeu’ta Melanie

Melanie Camman is also one of my peers. She is a MDES in Interdisciplinary Design candidate at Emily Carr University. Melanie, as she says, is a white settler in Canada. Melanie’s research explores her privilege as a white person and Iquebi’s story took us through the analysis of white privilege and decolonization. How the position of white people affects indigenous and racial minorities in Canada. We analyzed the similarities in how indigenous peoples in Paraguay and Canada are marginalized and their land is usurped. I told Melanie about the Ayoreos cosmology that says that humans come to the world to “be happy” and how they hold to that belief.

We also talk about how we recognize our ancestors and how to look back into the past, when difficult relations can deter us to do it. Can we select and skip generations?

Colloquy 4: Amombe’uta Bonne

Dr. Bonne Zabolotney is an associate professor at Emily Carr. She has a PHD in Design Studies. Bonne talks about the importance of context in design. When I told her Iquebi’s story, we reflected on how the design space sometimes needs to be “undesigned” to be able to work on it. How the voice of Iquebi got stronger because he preserved his language and his culture as his most precious values. I explained to Bonne how I define “Land-bordering”. It is the transmission of memories and lived experiences in the context of land and the different intersections that influenced that experience. Looking in this particular case into the indigenous way of being and doing of Iquebi and how his values and deep love for his land and his culture made him overcome the adversities. Through the role of “listener-messenger” I witness and bring up his voice to others. I share his story in order to build a dialogue that opens up other possibilities in the way that we as designers look at the place where we are situated.

Bonne told me that my project reminded her of a theory/concept developed a while ago by Allyson Lindberg, called Prosthetic Memory, where collective memory is shared and passed to others. With Bonne we also talked about Allyship and how white people can position themselves as such to build spaces of dialogue and hopefully of understanding and reconciliation.

We also discussed that indigenous knowledge is not a shared knowledge that a white settler or any person can just take to replicate or use (appropiate). Indigenous knowledge comes from Indigenous peoples and they are the ones to carry ownership of that knowledge.

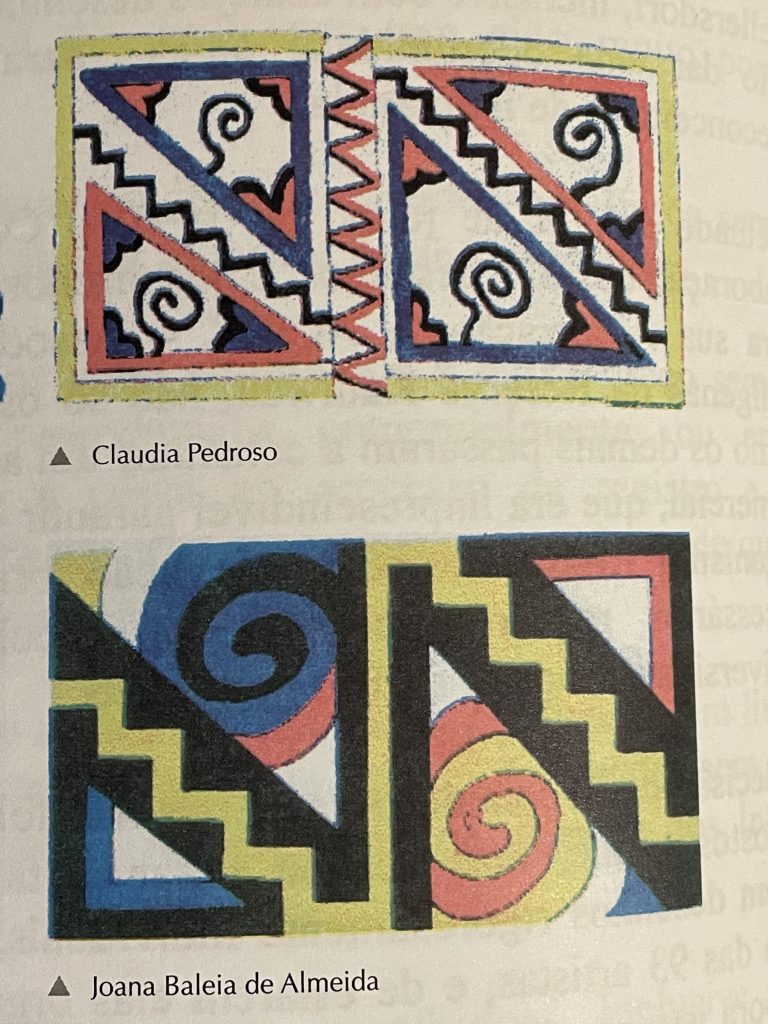

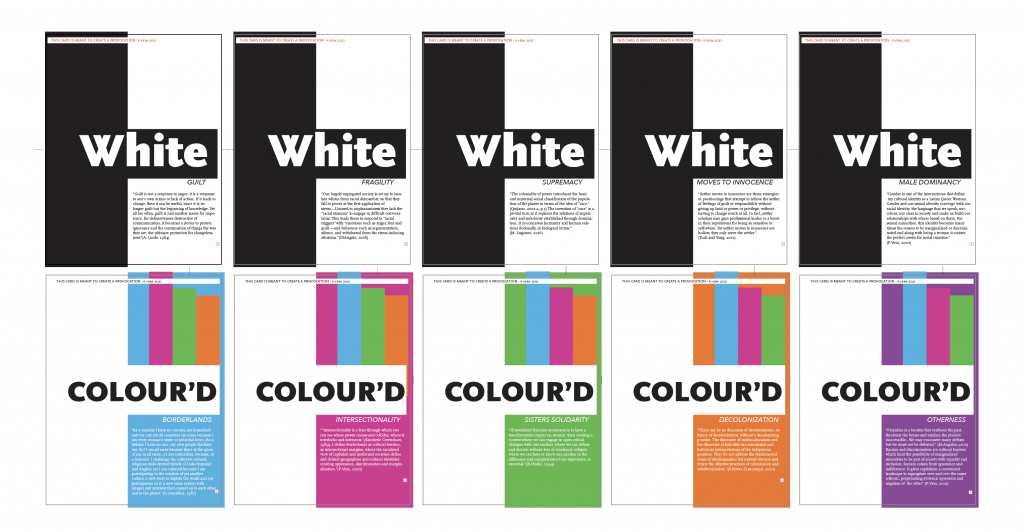

PROVOCATIONS

I put together a series called: Transgressing the Binary: White and Colour’d “tool” cards. They are a series of Provocations touching the key words that I take out from these colloquies. These “provocations” can be used in dialogues and workshops to bring these topics into consideration ,reflection and action.

Individual Images of each card are posted on page 2 of this blog.

KEYWORDS: White guilt, white privilege, white supremacy, white male dominancy, white fragility. Intersections, Borderlands, Intersectionality, Sisters solidarity, Decolonization, Otherness.

LEXICON

Eíra: honey

Ára: day, time

Marandeko (kue) tembiasakue: history, story

Tekovekue: ancient/past times.

Che: I/my

Nde, ne: You/ your

Ha’e: He/She

Ñande: We/us/our

Ore: We

Peê: You

Ha’ekuéra: They/them

Retâ/Tetâ: home ground

Yvy: land, soil

Queer: meña joja

Gender: meña

Kuña: woman

Kuimba’e: man

Pytu, yvytu: air/ wind

Tata, ata : fire

Ka’aguy: forest

Ama, Amangy: rain

Kuarahy: Sun

Kunu’u: love

Jasy: luna

Rera: name

Ara Rory jerovia: a day to be happy/hopeful

Amombe’úta ndéve ko ava tembiasakue: I’ll tell you his story.