Action 5: Video Sketch 1

In a group with Kimia Gholami

In Action 3, Kimia and I worked on decolonial design and had many conversations about it afterward. Around the same time we’d came across this article by chance in The New York Times “To Protest Colonialism, He Takes Artifacts From Museums” and it got us to think even more about the displaced artifacts all over the world. We both had our personal experiences around this issue so this encounter in the context of colonialism made us curious to go back and analyse once more.

The NYT article really got me thinking as I too have visited the Quai Branly Museum at the age of 18 in 2015. I was a young art student who had been reading the “art history” for a year and was over the moon to be able to see prominent art pieces in the Louvre. We didn’t plan to visit Quai Branly but just ran into it as we were walking around the city center. I was mesmerized by the interior as they were done in a way to enhance the mood with dark walls and partial lightings. In each section, you could hear the local music playing in the background which made me fall in love with an African tune and ended up purchasing the audio from the museum gift shop later. I had questions of course. Why are they here? How did they get here? I wanted more information, to know the stories behind each piece. They all looked so magical and each worthy of a lengthy description. But I couldn’t find my answers in the displayed information. The displayed descriptions and tags were minimal and some only in French. After all, I felt that I was lucky to be able to see them at least.

In the Louvre, I was in utter joy. Walked over ten Kilometers in it for hours and I couldn’t get enough of it. However, joy was one of the many emotions I was experiencing:

- Lucky and blessed to be there. Inspired by the rich collection.

- Proud to see a whole section dedicated to Persian Art. Proud to see my cultural heritage, the golden age of the Persian empire, being honored in a world-renowned museum that has numerous visitors from all over the globe.

- Disappointed. It was the first time that I could see the colorful tiles of Takhte-Jamshid in those great details. The ones in Iran, the origin, are very limited and have poor quality. I couldn’t put my camera down as I was scared to forget them later. Traveling to Paris was not something easy to achieve and I knew that I wouldn’t be back there in years.

- Angry & Jealous. There were many students in the Louvre. Sketching or even having a class right in front of a masterpiece. I thought to myself that these kids will have a much different/better perception of art than me. I’ll never have the chance to have daily access to an institution submerged in Art from all over the world.

- Offended and frustrated. I’m not sure about now, but back in 2015, all the museum information and descriptions of the pieces were in French! I was looking at an Egyptian ancient figure and I couldn’t even comprehend the history behind it. Information distribution in the Louvre was political, discriminatory, and racist, especially towards the objects with a non-French origin many of which brought here through colonial acts. It still baffles me to this day that how bizarre it is to move an artifact from miles away, perhaps by force and unauthorized, and while displaying it make restrictions on who can have access to the information.

Through this reflection, I was merely remembering my personal experience but I immediately realized my change of perspective over the past 5 years. I now can begin to understand the anger of Mwazulu Diyabanza when he saw his stolen heritage up on the wall. Looking back at the moody interior of Quai Branly Museum, although atmospheric, it was trying to exhibit these artifacts as decorative objects, while they were and still are part of some people’s identities and cultures. They had eliminated the voices behind those artifacts (literally and figuratively) and took over the power of storytelling while ignoring the real stories and the real people involved in them. They displayed them with a certain ambiguity that turned those objects into strange crafts, alienating their creators.

What is clear to me is that institutions such as The British Museum, Louvre, and Quai Branly that hold onto objects from other nations, should seriously reconsider their policies and politics. Open conversations should happen and the right voices should be heard. I talked about my personal feelings, not for generalization, but to point out that this is perhaps a subjective matter, and this is definitely about people. Some countries have asked for cultural property repatriation. However, western museums initiated zero to little action. The British Museum justifies holding to the looted objects by considering itself “a true library of the world”. In the meantime, I, as an Iranian citizen, can’t even get a visitor visa from England, especially now with Brexit in place. The museum is kind enough to lend the items, still ignoring the matter of displacement, claiming ownership, and even making a profit through lending objects. This is perhaps just a polished form of coloniality.

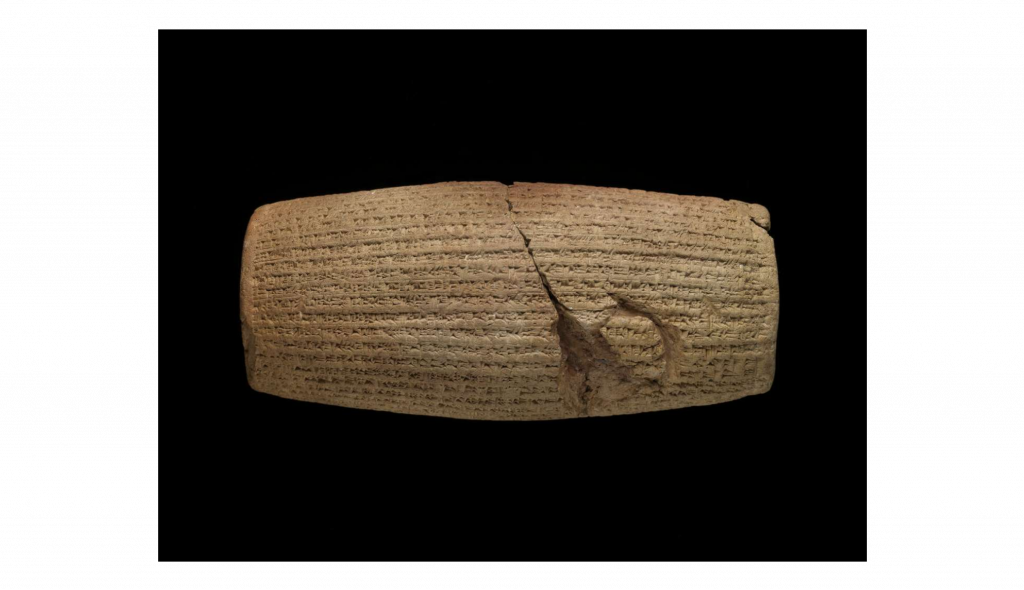

The Cyrus cylinder is one of the most prominent artifacts from the Achaemenid Dynasty (Hakhamaneshian – هخامنشیان) and amongst the many objects displayed in the Ancient Iran section of the British Museum. Clearly, I won’t have a chance to see it, and even if I will, it would cost me fortunes, and it would be a temporary visit. This makes us revisit the statement of “a true library of the world” because from where I stand, this library serves the interest of a privileged few.

no comment.

What makes this argument and some similar instances controversial is the fact that this object was found in an expedition funded by the British Museum. So in a way, one could argue that if they hadn’t excavated, maybe we wouldn’t have found it in the first place and that’s why they can claim ownership. But this hypothesis can never be truly assessed. What we know is that people are the most important component of cultural and historical heritage. Without people, these crafts wouldn’t even exist. Furthermore, many of the looted artifacts of the First Nations hold invaluable knowledge and values for indigenous people which they’ve been deprived of. This displacement has faded histories and disregarded people.

How can we right the wrong? Can we even compensate for the cultural loss in many nations? Who can claim ownership? The only answer I have in mind is to amplify the voices that need to be heard and start conversations. People are at the center of this issue, not the governments nor the prestigious institutions.