Action 6 | Grad Studio I

This action started when I randomly decided to fix a floor lamp that I had in my room for years. A couple of years ago and during our house move, the lamp got slightly broken and cracked in its plastic material. Over time, new cracks were made into it, so I decided to take action and repair it! I had already written the term “making with natural materials” in my action6 declaration form, so I decided to make a replica of the material that was used in the lamp using only natural materials to substitute the current one.

Cornhusk was something I thought about randomly. Initially, I went to the park and gathered some materials I thought could be useful, but none of them seemed soft enough to create a flexible material. So I began thinking about the materials like orange peel and potato peel, materials that would otherwise go to waste. Suddenly I realized that every time we have corn for dinner, we throw away a large amount of corn husk that seems like a suitable material to work with for this project. So one night after dinner, I gathered all the cornhusk that was going to end up in the trash and set it aside.

Part I:

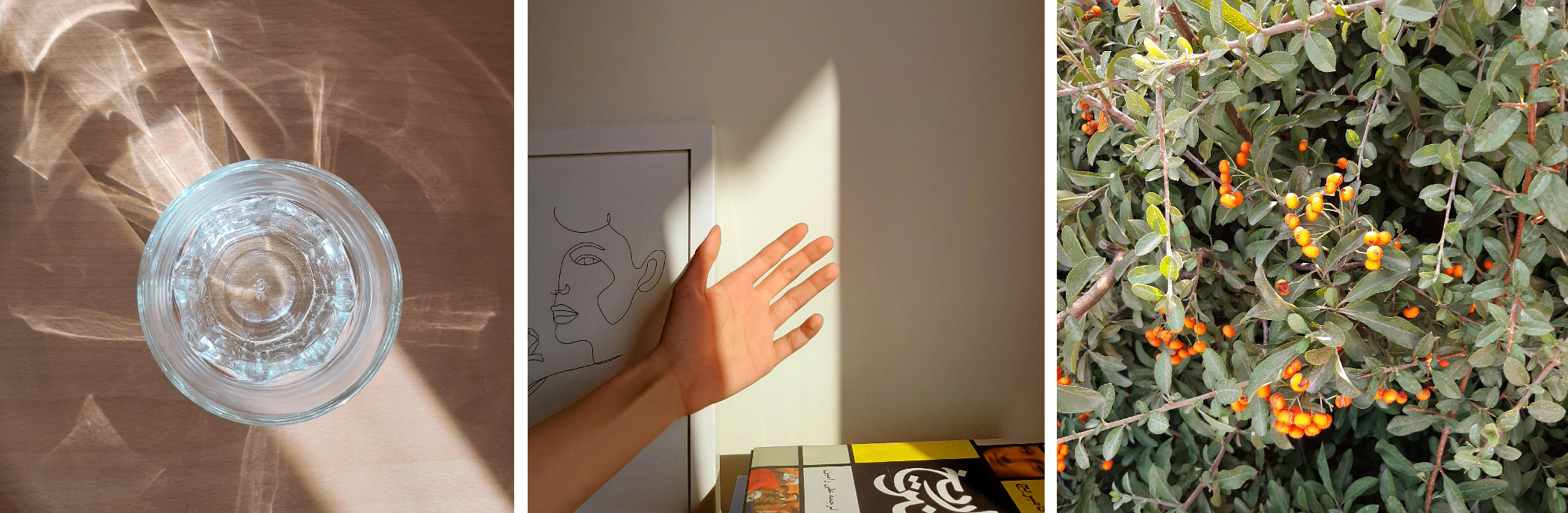

I started by carefully examining the material and analyzing its features. Its transparency seemed like something I was able to use to my advantage in this case since I needed a material that light would pass through. As I examined the pattern, I decided to experiment with some natural/organic colors and dye the pieces to create a more colorful palette for my end material.

I had started rummaging through the stuff we had in the cabinets to find natural dyes when I remembered this old tradition we do in Iran. When celebrating new years, we gather different items that each represent a symbol, and one of those items is colored eggs. Nowadays, everyone uses ready-made paint to color them, but I remember back when we were kids, we mainly used natural materials. One of those was red onion peel, which produced a coppery color. So I decided to start with that. After boiling the husks in a pot with onion peel, I found other natural materials like barberries for red, chard for purple, carrot for orange, and turmeric for yellow.

I boiled a few pieces of husk in different pots of each color and waited for the result.

At the end of the coloring process, I was quite surprised at how well most of the cornhusks had absorbed the color and how vibrant they looked.

I let the pieces dry completely, and then I ironed them and applied pressure. The result was quite interesting. The yellow ones had lost some of their vibrancy, the red ones(barberries) were not as sharp as I had hoped for, and the orange dye(carrot) barely gave off any color, but the chard (purple) and the red onion(copper) were the best outcomes.

Another interesting thing I noticed was how the colors I used on the cornhusks all had different effects on their texture. The copper made the cornhusks stiff and brittle, and the yellow made them darker and thinner. The red one ended up being the most flexible of all four.

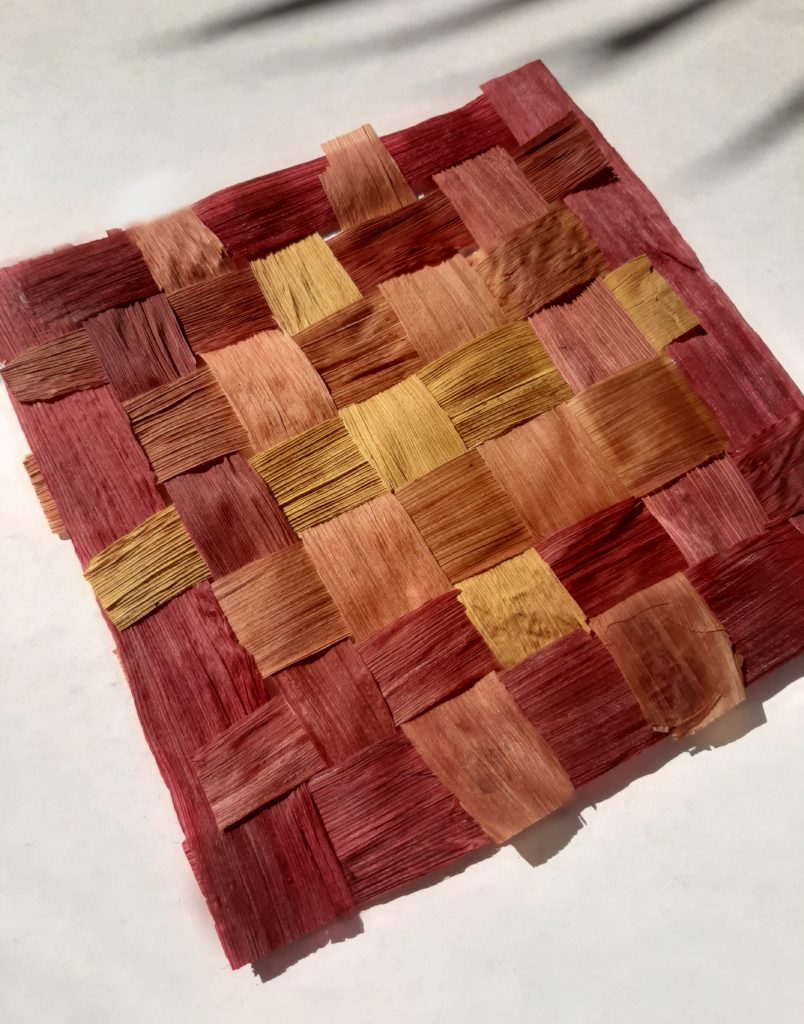

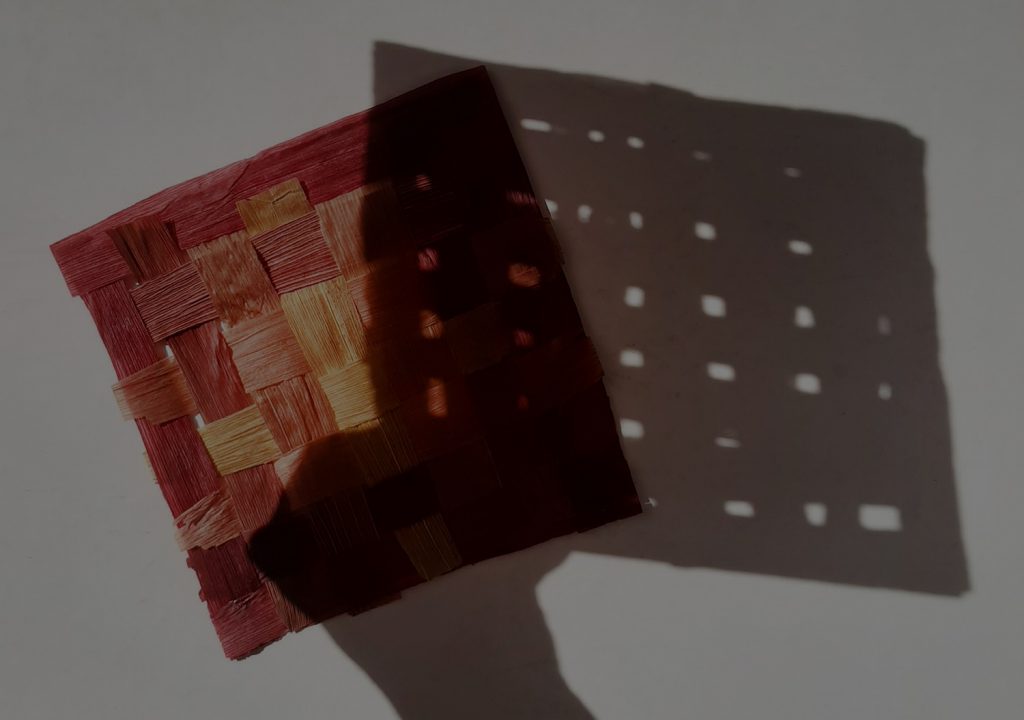

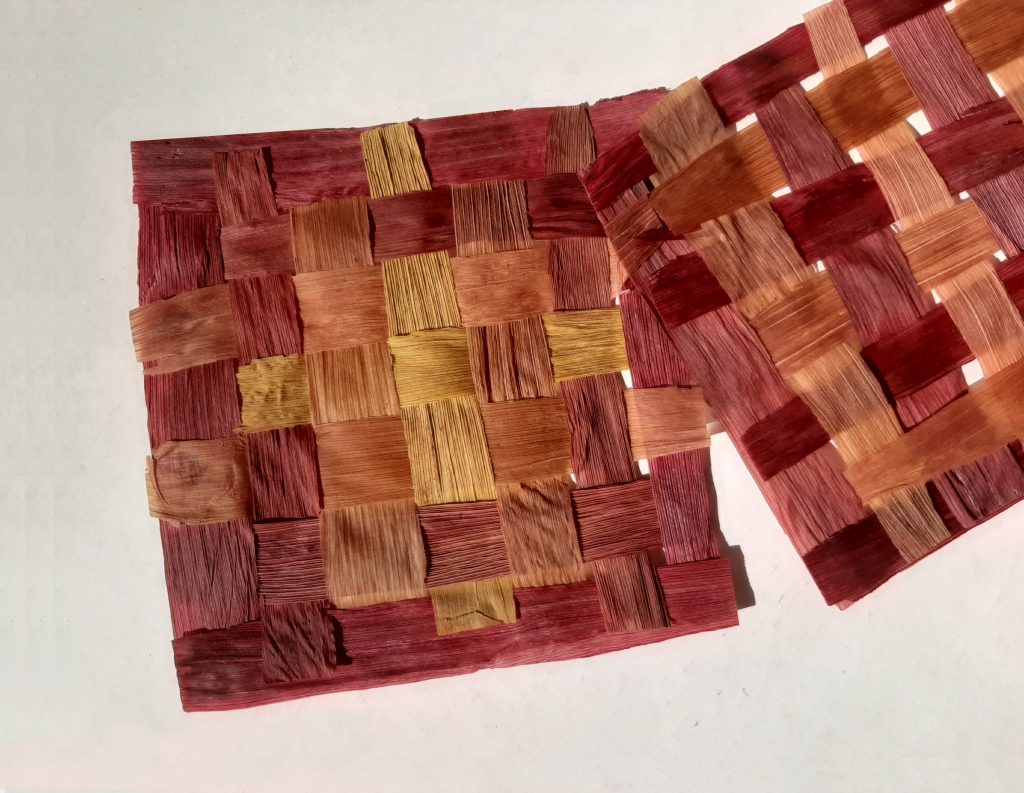

My initial thought was to weave something like a fabric out of these pieces using a gradient-like color pallette. I cut the husks into long threads and started weaving using the simplest technique. I immediately realized that I had made a mistake by letting the husks completely dry. The process would have been much easier if I had done this when the pieces still retained some moisture.

In the end, I created two sets of color patterns through weaving.

For the first try, I took out the broken surface and replaced it with the new woven “fabric”!

Part II:

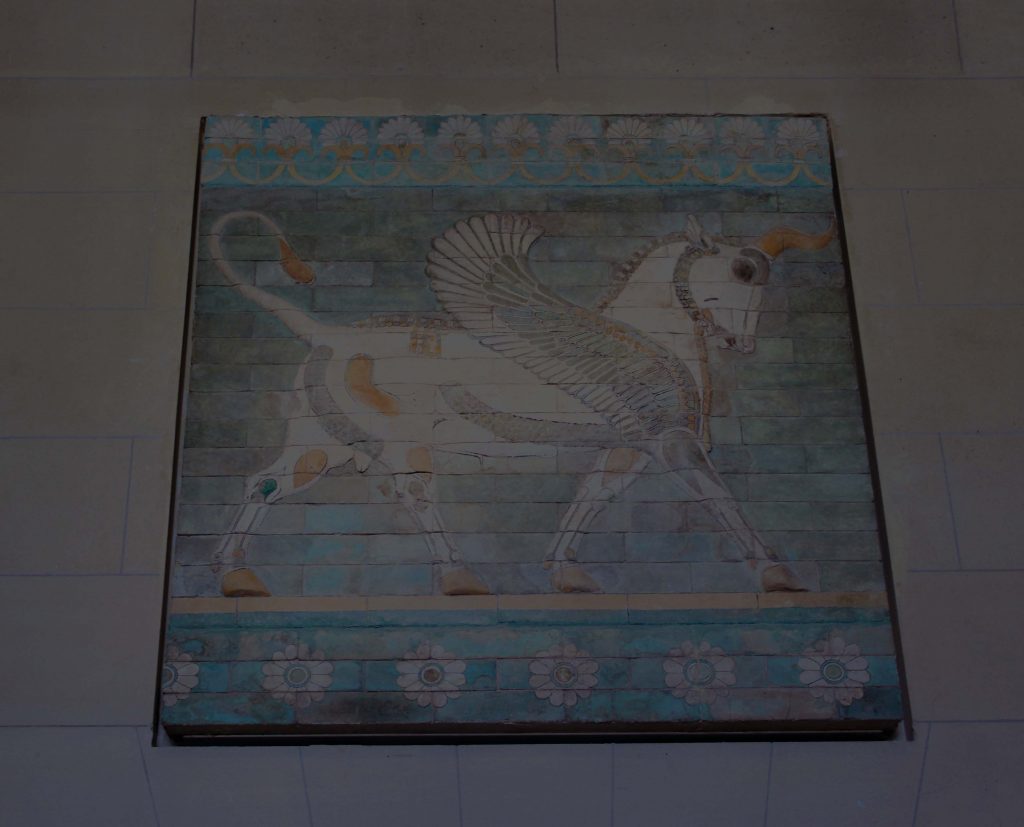

After replacing the old cracked material with the new woven one, I was going to put the broken surface in the recyclable trash can when I thought to myself: wait, did I just produce more trash by doing this? Should I have left the cracks live their life in my lamp? In the end, it wasn’t that big of a deal! Was what I did even repair? While thinking, I suddenly remembered a chapter of Daniela Rosener’s book critical fabulations. In one of her projects called the broken probes, Rosner had explored the legacies of repair through the Japanese art of kintsugi, a practice that uses visible gold lacquer to highlight cracks in earthenware. This project was all about embracing beauty in the flawed since our modern perception of aesthetics has been formed based on clean, flawless, and smooth objects. Rosener attempted to challenge this thought by creating an alternative to our mass-produced goods.

So, I started thinking about embracing the cracks in my old lamp as its history rather than flaws. Replacing this broken material altogether and adding to our already large amounts of trash was erasing the stories behind each crack. I decided to put the old material back and create a material that would just fill the spaces of the brokenness and not the whole thing.

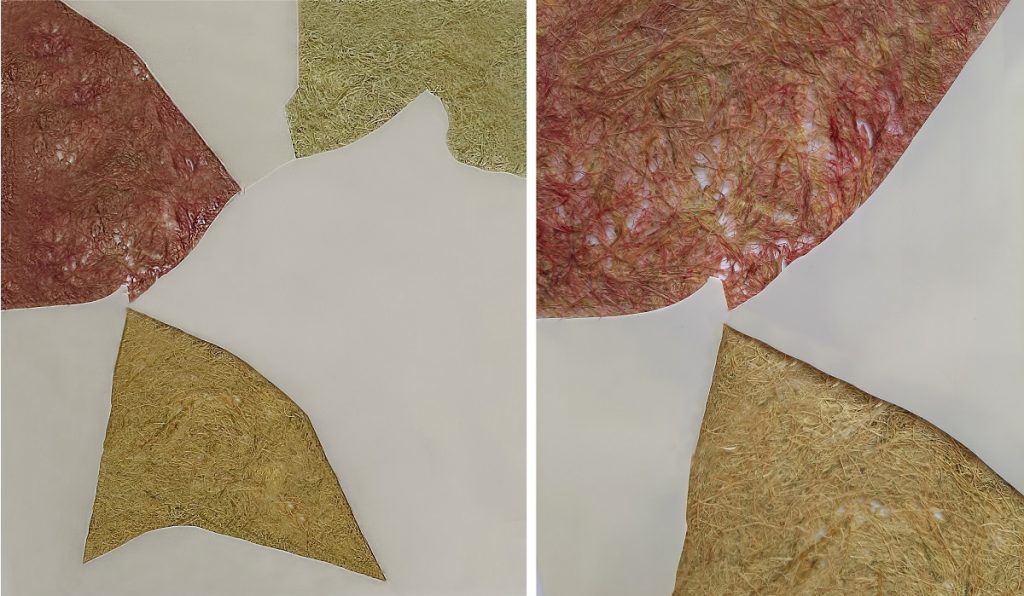

For my second attempt, I wanted to create another material just to further explore working with natural things. For this part, I went through a process similar to hand-made papermaking using the rest of the cornhusks that were left. I also used some of the leftover colors from my first attempt. I decided to create three different papers, each one representing one cracked piece. The process of making this was so therapeutic that I completely forgot to document it with pictures!

I put these three prices together in the shape of the cracks and replaces the first material with this one.

Reflection:

1.Not just vision:

After reflecting on this action as a whole, I started thinking about the aspects of it that I massively enjoyed. Working with my hands and working with tangible materials that had smells and textures was definitely one of them. I feel like our modern perception of understanding things has been heavily based on vision and nothing else. So we have lost touch with our other senses. This especially matters since we live in the era of technology and dematerialization. How can we bring back our other senses to design?

2. Materializing time:

Time is a tricky and amorphous concept. We don’t see it, but we see its impact: especially on ourselves as we grow up and grow old, and on our environment. Nature is the perfect embodiment of time; The colors, weather, and growth. Even the inner rings of a tree represent time. It doesn’t hide it, but it celebrates it. Objects, however, are not the same. The truth is, we don’t want them to be the same. We want our objects to be in perfect shape. We have good reasons for it though. In a fast-paced world, no one has the time or the energy to deal with a less than perfect product! But maybe just for some objects we can let them age and embrace the unique history behind it.

3. The art of repair:

In this action, I also explored the art of repair. By looking at objects beyond their functional layer, we can appreciate their values. Objects are living entities that go through different stages of life; They change and sometimes break. Kintsugi celebrates the breakage by seeing it as an event in the life cycle of the object. Instead of throwing things out and creating more waste than we already do, could we look for better means of repair?

4. Going back to the basics:

Starting this action, I hadn’t thought about the old tradition of egg coloring when I was a kid. As I grew up, we all somehow forgot about this. No one bothers to use natural colors anymore, we all use paint. But perhaps we should start reframing our approach? Again, this is a very small example but maybe going back and revisiting some of our old habits is worthwhile. In a world that is focused on consumption and waste, how can we meet our needs within the ecological boundary of the planet? Is going back to some of our old routines a part of the answer?