Rituals

“Slow knowledge” has been formed through long periods of time where individuals or communities tried something that felt right and worked right. Practiced over time, these can become traditions.

I believe that traditions and rituals are interwoven. I habitually practice my own traditions enough to call them rituals, or do my rituals form my traditions? Which way does it work?

My morning ritual:

Each morning, I like to wake up before anyone else while it is still dark out.

I open the blinds and in summer, windows as well.

I start our electric kettle.

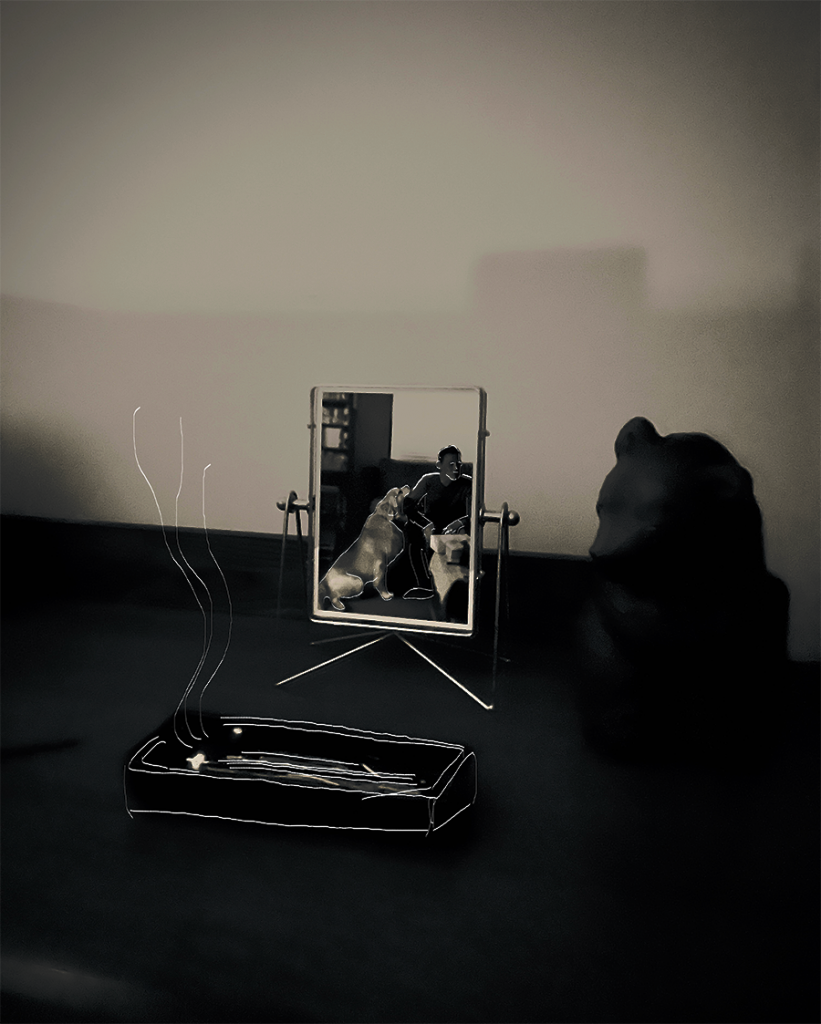

I light Japanese incense by my uncle’s photograph who passed away and say good morning to him just like we used to say to each other.

I water the houseplants.

I let the dogs out to the backyard. And then feed them.

I make tea or coffee for myself.

I then turn on my computer and check news as I settle in for the day.

Why light incense? I am like most Japanese. Sometimes we do things out of inherited habit. Growing up seeing my grandparents pay respect to their ancestors by lighting incense in front of our Buddhist altar (even though they were not Buddhist), was what I was accustomed to seeing daily. Me doing it now just seems like the right thing to do. It ties me to my ancestors and to my uncle who I was very close to; he passed away last year.

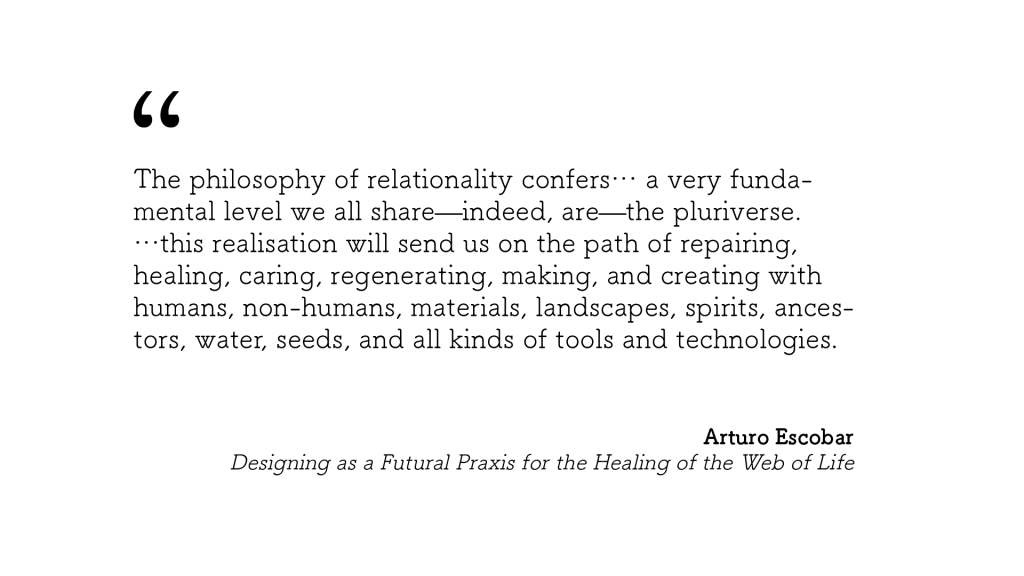

These rituals that are part of me – they connect me with my world. And even though I am not religious (as most Japanese), my culture is deeply spiritual. We believe in interconnectivity and we are all connected to everything around us.

Yoko Akama is an Associate Professor in the School of at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia. She studied and researched how “Japanese practices live between worlds” (p. 5, 2020). Akama explained that Japanese practice everyday spirituality based on Koshinto.

“Koshinto” is inter-relatedness with rocks, mountains, trees, animals, lands, waters, wind and people, imbued with spirituality…Koshinto [is] a view that the natural world is made of a community of spirits of which humans are just one part.”

There are many curious customs in Japanese culture. These customs and rituals are part of me. Perhaps this is a way that I am connecting to my ancestors and heritage; perhaps this is slow knowledge being practiced by me. I realize that slow knowledge does not just have to be mechanically or physically oriented. It can be spiritual too.

My intention going forward is to continue to explore my connection with nature and the interrelatedness of all things through the combined lens of my Japanese heritage and my life as a Canadian.

Reference:

Akama, Y., Light, A., & Kamihira, T. (2020). Expanding Participation to Design with More-Than-Human Concerns. ms, New York, NY.

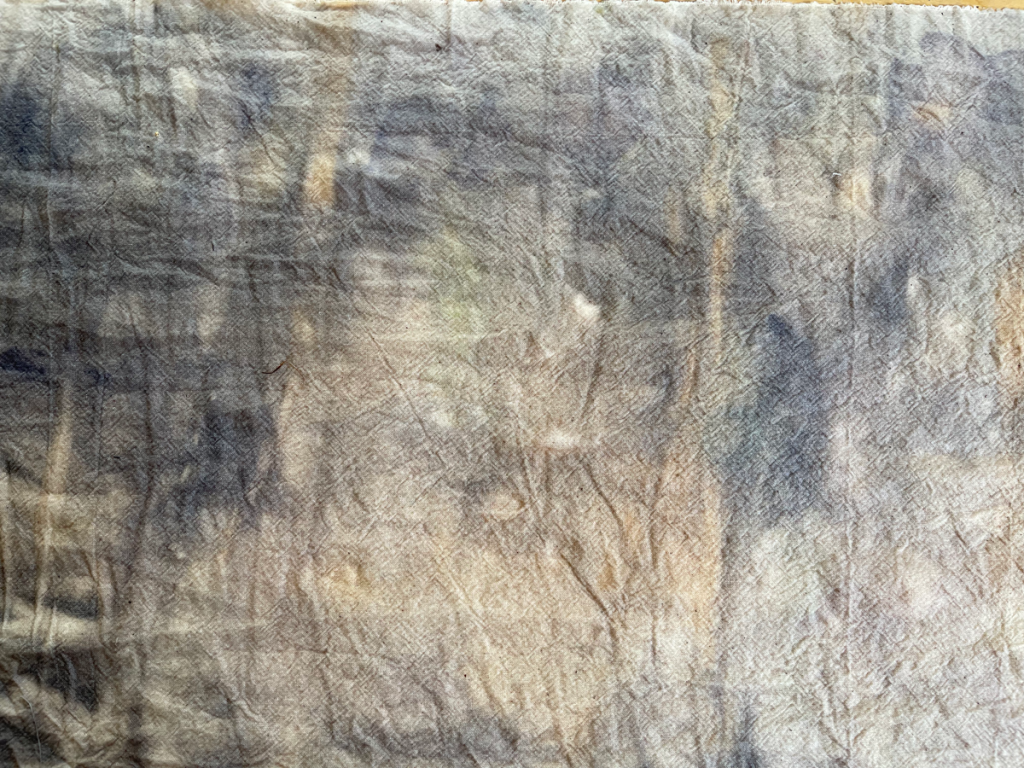

Yamanouchi, D., (08/2021)Yasaka Shrine Shinboku, Chiba, Japan