INQUIRY

Understanding My Rituals

After my previous prompt that focused on my daily rituals, I was left to think about why I practice these rituals. This is something I have not looked into with depth before, I just accepted what I do, not realizing the source. Many of the rituals I perform are mimicked from what I have seen my family and others do. How I pay respect to my late uncle is a reflection of how I saw my grandparents and my parents pay their respects to relatives. There are so many customs and activities that I have inherited and share with others raised in Japan. The way we admire Mount Fuji, the sunrise, and the full moon, how we visit the graves of my relatives who have passed away, to how we tilt our umbrella as we pass others, and how my grandmother always had a fresh flower arrangement in our bathrooms… these are a few examples of our unique customs. While they are part of me, I find it challenging to explain my customs and beliefs to others, particularly those raised in a western culture. Part of the issue is that many of my customs are embedded in my being. I am not sure I can explain them in a way that those who were not raised in the same culture can understand. I am not sure I even understand my customs and beliefs.

How Westerners View Japanese Culture

Mari Kondo has made the Kon-Mari method of mindfulness and cleanliness famous to western culture. However, I am a little surprised at how she is synonymous with what she is teaching. To most Japanese, she teaches something that we all grew up with and know inherently. Ensuring that we appreciate what we use-books, dishes, etc.- is part of our culture. Kondo has just been able to articulate it in a way that makes sense to other cultures.

I was also surprised when I saw how a movement around “Wabi-Sabi” had become popular over the past few decades. In a book written originally in 1994, Lenoard Koren explained that “Wabi Sabi” is “a beauty of things, imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.” When British author Beth Kempton learned about Wabi Sabi and wrote about it in 2018 she explained how “Wabi” finds beauty in simplicity and is “spiritual richness detached from the physical world”. She said that “Sabi” is concerned with the passage of time and how all things “gown and decay and how nature alters the visual nature of things” (01:45 – 02:02). I understand what these authors are saying, but how they explain our beliefs and customs is insufficient.

There is something more about Wabi and Sabi and valuing things, but exactly what is hard to explain and comes from deep within me. I realized this might be due to how we learn about things. I find it interesting that after a few decades of living in Canada I am beginning to understand that I am influenced by both my Japanese culture and my experience with western culture. But to really understand myself and my values, I need to start by connecting with my origins to see how this influences everything I think and do.

Observation, Mindfulness, and Appreciation

Kempton stated that Westerners need to have things written down because that is how they have learned to acquire knowledge. Japanese still, after many millennia, learn by observing and doing (01:12 – 01:30). This ability to observe is more than just looking at something. It is the contemplation of things. And through mindful contemplation, appreciation comes- at least to me and others in my culture. Author Steve John Powell stated that while mindfulness is now popular around the world that it has existed for many centuries in Japan (2017). The origination of mindfulness and appreciation seems older than that to me.

Connections with More than Me

Yoko Akama was one of the first authors that really helped me make sense of my worldview. Because she has lived in Australia for decades, she, like me, has been influenced by western thinking. From her writing, her cultural upbringing factors into her personal worldview. Her research in Expanding Participation to Design with More-Than-Human Concerns related to how the Japan’s historical spirituality affects how Japanese view and act in the world, and was eye-opening for me. Concepts such as “yoriai”, “an unhurried system of collective decision-making” (p. 6) started long ago in towns and villages across Japan. People in committees would gather in their local shrines to discuss all matters that influenced their communities. This concept of community continues to flourish today in Japan.

While I was growing up, I remember my grandparents being active in our neighbourhood. The yearly community festival at local shrines has been going on for hundreds of years in each community-even in the middle of Tokyo. I remember a volunteer going through the neighbourhood every night at nine o’clock hitting two wooden sticks together, calling out “Hi-no-yojin”, which direct translated means “precaution to fire!” In traditional Japanese communities, houses were constructed of wood and clustered closely together. Even if the construction materials have changed, the clustering remains consistent today. The danger of a fire spreading from one house to another is much higher. So, “hi no yojin” reflects the understanding that the entire community relies on each person’s attention.

A “more than me” concept is imbedded within Japanese culture. Akama gave an example of how a Japanese shrine is not just a shrine with functional purposes where you go to practice rituals, although none of this would be false. “Shrines are not mere buildings…[Shrines] are sentient beings with a living presence that is (and has always been) interrelated with cycles of creation and destruction” (Akama, 2020, p. 6). We Japanese have a consciousness that there is spirit and living in everything and therefore the purpose of everything comes from its own source interrelated with us.

Cleaning and More-Than-Me

Learning about how my views, customs, and rituals are quite spiritual and originate from my culture thousands of years ago, I started to think of all the ritualistic activities or actions I have done that on the surface seem quite mundane but bear deep meaning. Cleaning objects is an interaction with things that every child in Japan experiences. Japanese children from kindergarten to the completion of high school learn to appreciate the items they use in school. John Powell and Angeles Cabello attempted to explain that the desire to keep their belongings clean comes from Buddhist and Shinto beliefs that things that are dirty or stained can harm us. I feel that this may be partially true, but this view makes the cleaning of objects more about the humans versus the objects and does not include the more-than-human view that Akama explained.

I suspect that the moral lessons I received as part of my Japanese learning in school, accompanied by me viewing and observing my family and people around me treat things with appreciation and value, accompanied by the honour I saw my family place in all our inanimate objects became embedded in me and slowly infiltrated my core allowing me to develop a deep appreciation of all things living and non-living. If my feelings towards other things are a result of my upbringing and my culture, I wondered if those same feelings could be developed in others that do not share my cultural development.

Akama stated that we don’t even realize spiritual connections we have to things around us – spirituality is inside us. I thought if this is the case, then perhaps we just need to uncover our inner spiritual connections. If Japanese children are able to develop a connection with inanimate objects through taking care of them and being more mindful about them, I wanted to explore if these same feelings of appreciation, and eventual empathy towards “more than humans”, could be developed by those who did not grow up in Japan by utilizing similar techniques used in Japan.

Exploration

Micro Action Exercise

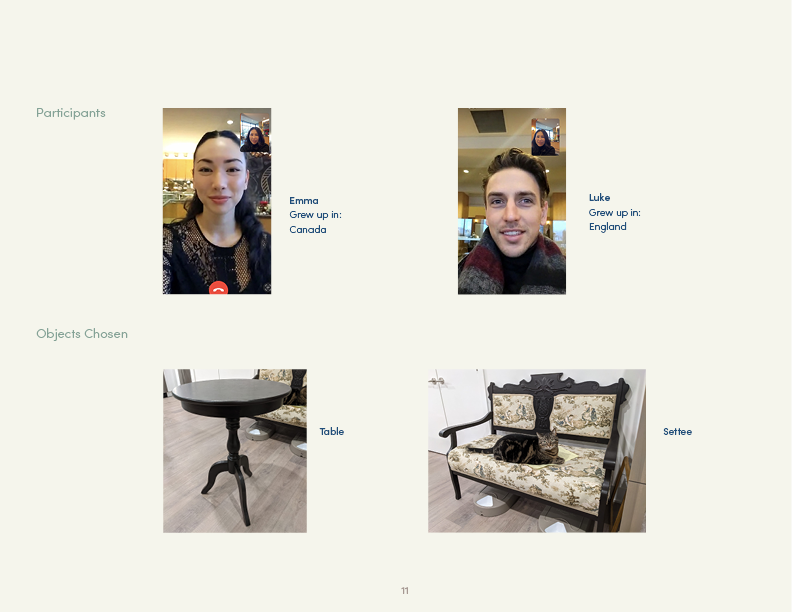

I decided to conduct a micro action exercise to try to see if taking care of inanimate objects could develop some type of spiritual connections for those not raised in Japan through practicing a cleaning ritual.

Length of exercise: 6 days

Object: Choice of the participants

Prompt given: Daily

Action: Following daily prompt to dust/ clean the object of their choice.

Results: After each prompt is performed the participants will record their thoughts/feelings and share them with me.

Thoughts and Conclusion

This micro exercise gave me some insight and hope that it may be possible for others to develop empathy towards inanimate objects through taking care of them, and a number of additional questions came to me that helped me realize additional aspects to consider in the future when researching this subject.

I noticed that the mere action of cleaning or taking care of something did not seem to alter or influence their feelings. Luke’s comments of feeling the exercise was mundane and mechanical told me that he was not uncovering a connection with it. The object was still quite separate from him and existed to serve a purpose that was functional to him. When I gave additional information and instructions both were able to identify its usefulness, but I am unsure if this understanding (of its usefulness) impacted how they felt about it.

I was interested to see that Emma, after six days, said that she will notice the table more every day and that she “likes it”. I wondered if this was a spark of feelings towards the table. Because I know the participants and know that one has Japanese roots (my daughter) and the other European roots, I wonder if and how this influenced their perspectives as they moved through the prompts.

I also wonder how time plays a factor. This exercise was six days only and each prompt was concluded in a matter of minutes. If the participants interacted for lengthier periods of time and over a longer duration how would that influence their feelings towards their objects?

Certainly instruction seemed key. Without instructions to specifically contemplate how the objects helped them, it appeared that the participants may not have developed an appreciation for their objects. This leads me to want to find out more about how specific instructions and teachings influences our feelings towards inanimate objects.

Finally, I wondered how an individual’s personal spirituality affects their views towards more-than-human philosophy. For example, if they are a spiritual person who believes that humans are connected on a spiritual level, is it easier for them to make the jump to developing empathy to inanimate objects than those who do not think humans are connected spiritually?

All of these questions have opened up numerous additional research possibilities for me, and this is both exciting and daunting as there are so many directions I can go. However, as the individual constructing the exercises, I started to understand how important planning all aspects of my research is. ■

References

Akama, Y., Light, A. & Kamihira, T. (2020, June 15-20). Expanding Participation to Design with More-Than-Human Concerns [Conference Presentation]. 16th Participatory Design Con ference, Manizales, Colombia.

Crossley-Baxter, L. (2020, April 27). Japan’s unusual way to view the world. BBC Travel. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20181021-japans-unusual- way-to-view-the-world.

John Powell, S. & Marin Cabello, A. (2019, October 7). What Japan can teach us about cleanliness. BBC Travel. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/travel/ article/20191006-what-japan-can-teach-us-about-cleanliness.

John Powell, S. (2017, May 9). The Japanese skill copied by the world. BBC Travel. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20170504-the-japa nese-skill-copied-by-the-world.

Kempton, B. (2018). Wabi Sabi, Japanese Wisdom for Perfectly Imperfect Life (B. Kempton, Narr.) [Audiobook]. Harper Design & Audio.