On diaspora.

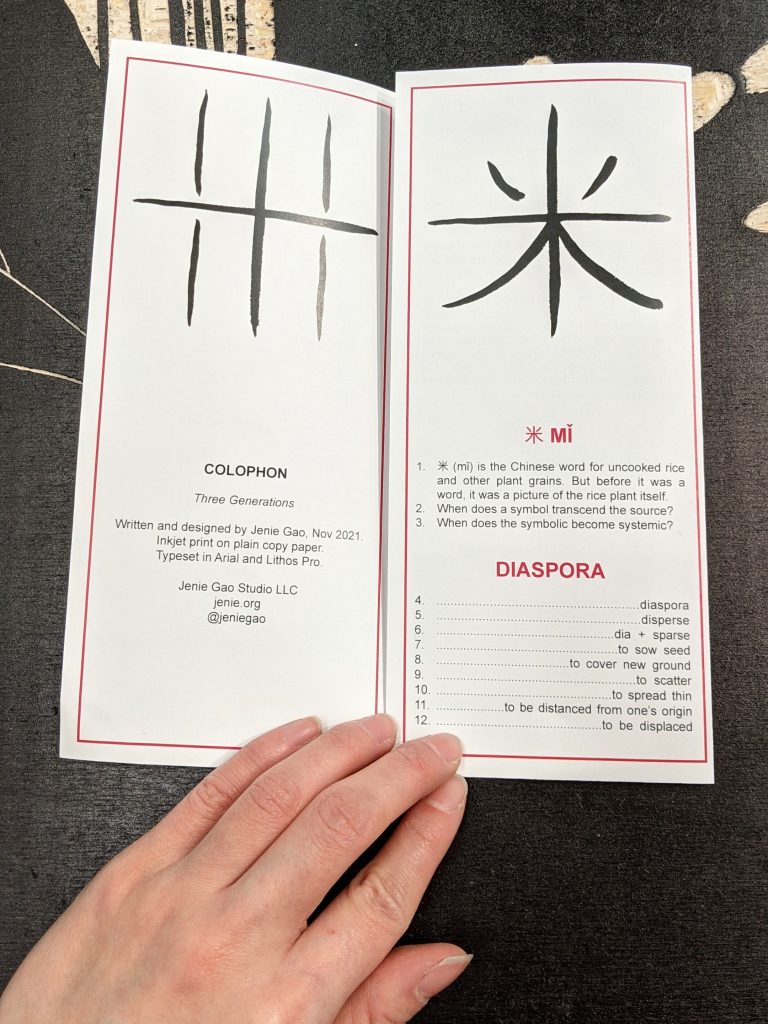

When my Ma saw this woodcut, she said, “I can tell you were raised in the US. No one taught you how to write Chinese.” This print is a metaphor for diaspora, but even so her comment stung. It hearkened to times in my childhood when over something seemingly small, my parents would say, “You’re not Chinese.”

My mother was commenting on the style of my writing. Too straight. Too even. Ignorant of the fact that we should write our words from the perspective of the heavens. I *am* ignorant of the heavens–between having a dad who survived the Cultural Revolution and my own American assimilation, I am far removed from tradition.

I’ve heard other comments in [white] academia. That using Chinese made it inaccessible and not “universal” because they couldn’t read it. That my perfect lines couldn’t possibly be drawn by hand (they are). That my precision somehow makes information less believable, less human. Except precision is the tool of those who grow up in chaos, to steady an unstable environment. Precision is the tool of women, who cannot get away with sloppy craft like men can. Precision is an extraordinarily human trauma response.

When I showed this work to other Chinese Americans and diasporic Asians, we shared an immediate, cathartic understanding. As for my Ma, for the first time, she said, “Your dad and I thought it was better for you to assimilate. I’m thinking now we created a barrier for you to know an important part of yourself, a part that you need as an artist.” My handwriting created a bridge for my Ma and me to relate to each other.

There’s something refreshing about being wrong, in a system that demands women of color to be better in order to be equal. To be illegible to western society. Impious to filial duty. And from this, as a daughter of the diaspora, the chance to create a cultural perspective of the world that is my own.