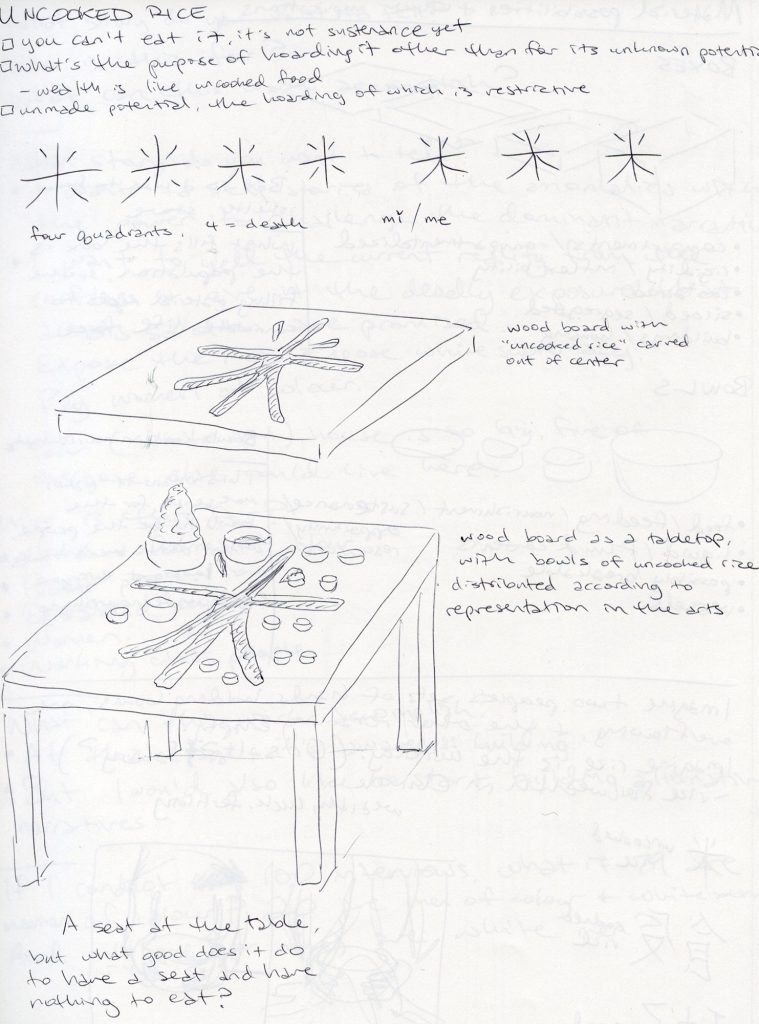

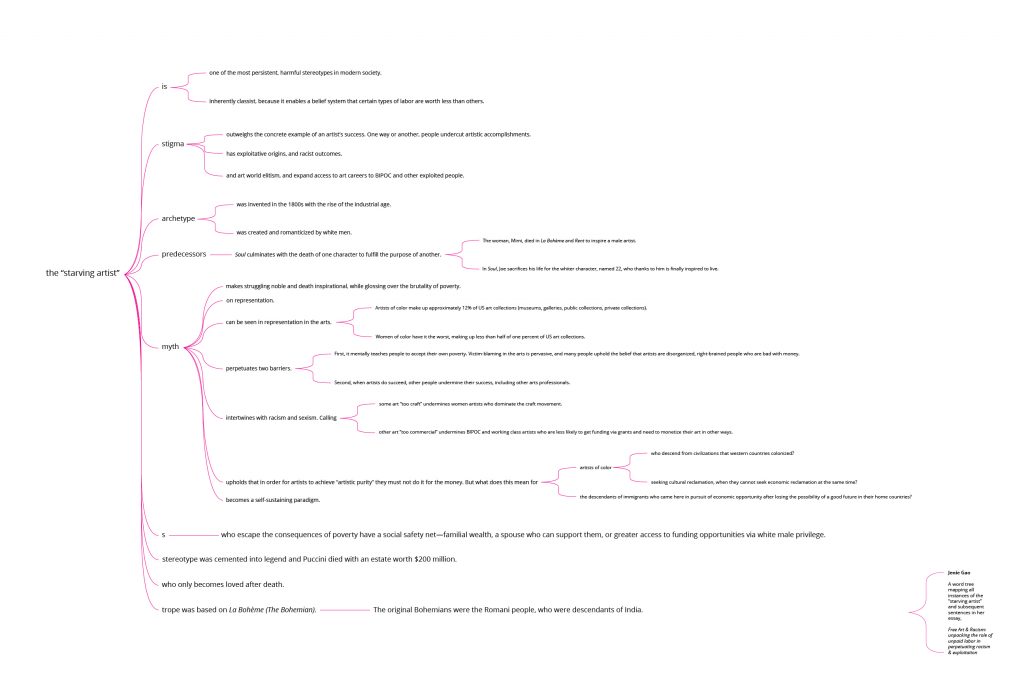

It Takes Three Generations is the second iteration of my 米 mǐ | uncooked rice series.

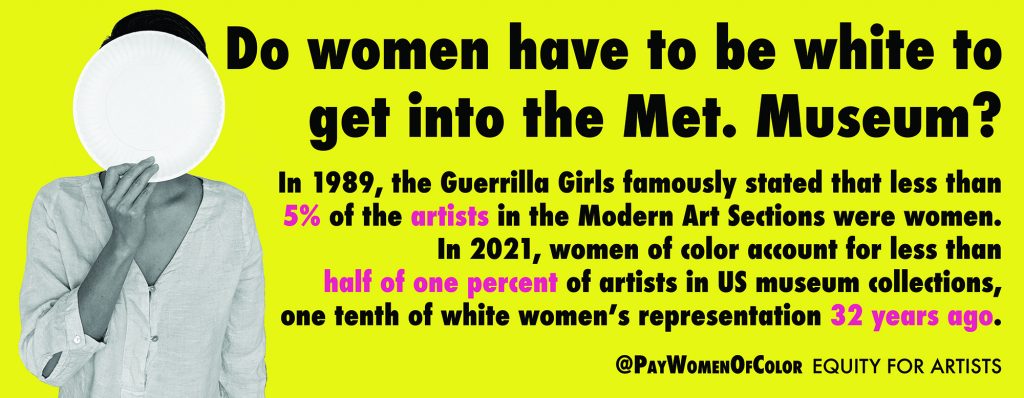

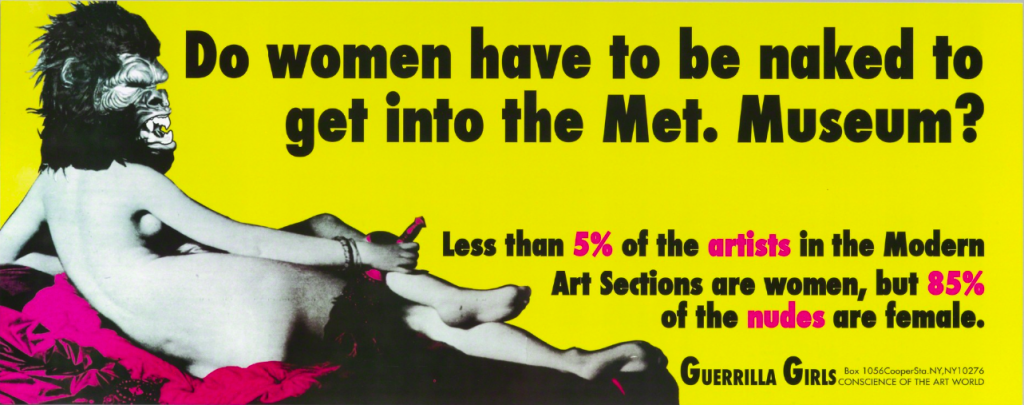

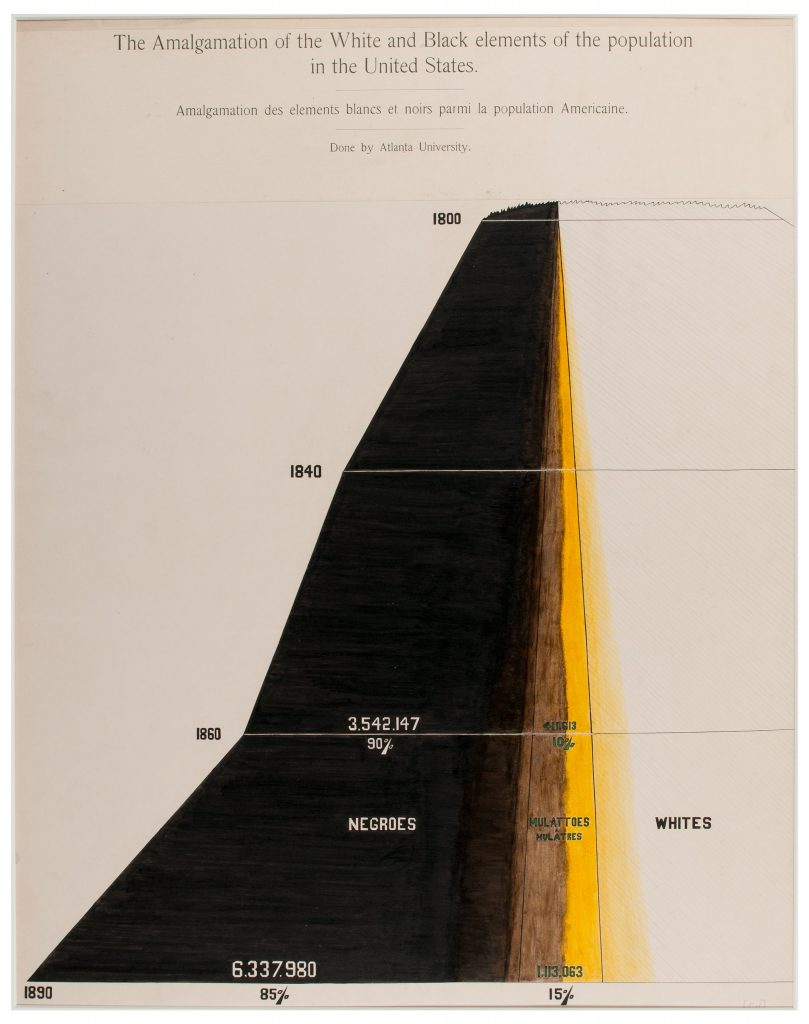

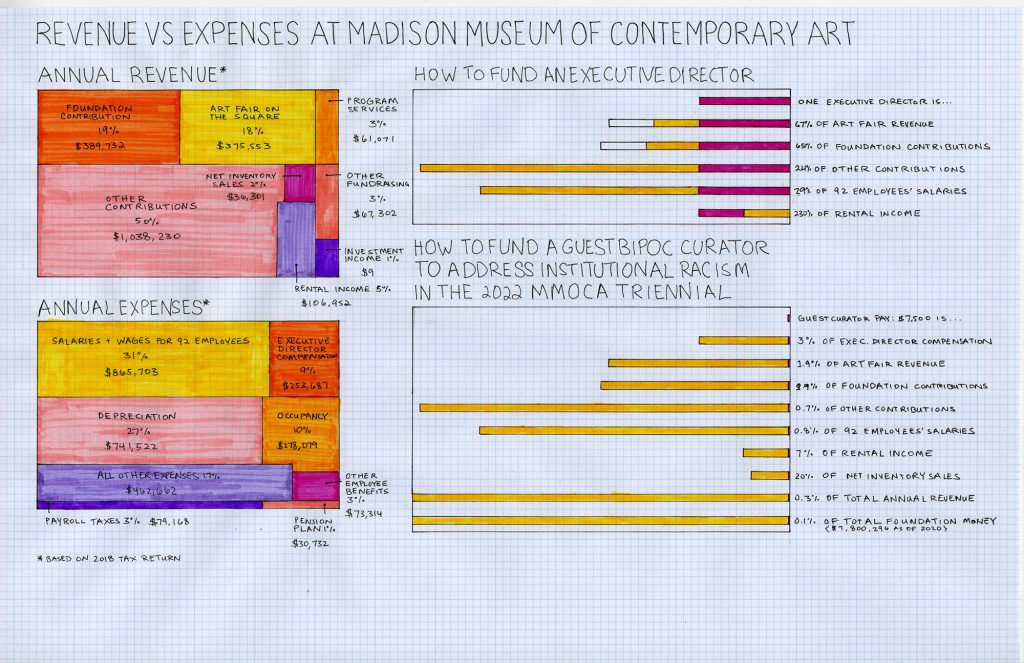

米 mǐ | uncooked rice is an installation based on representational disparities in the US arts industry. mǐ is about unfolding the emotional and personal core for why this data matters, to reveal that underneath the numbers are people’s lives.

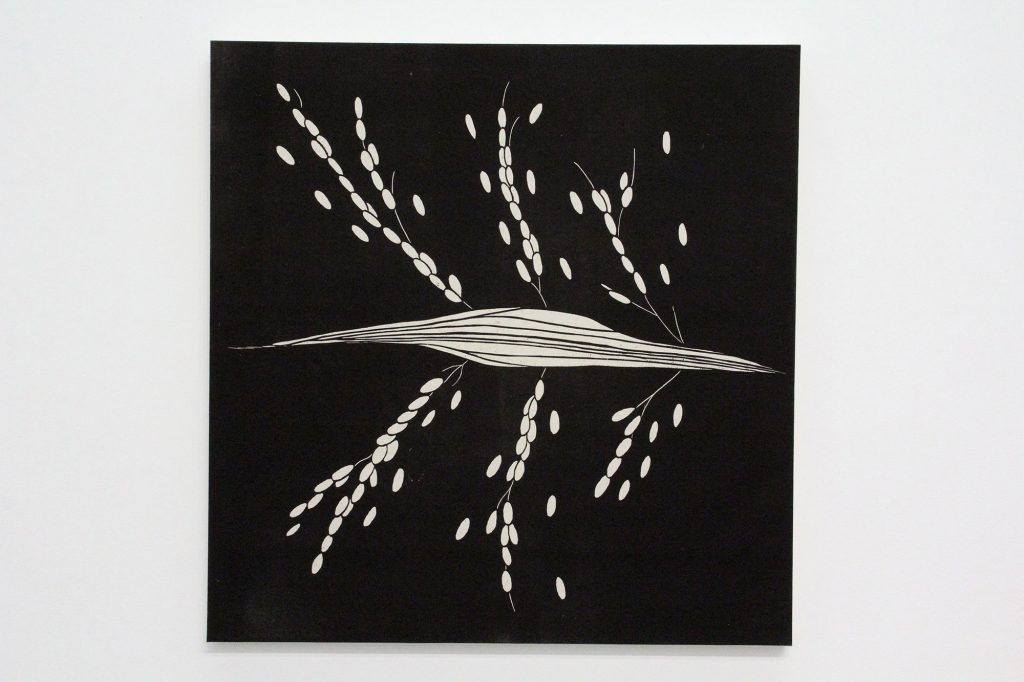

米 (mǐ) is the Chinese word for uncooked rice and other grains, a metaphor for that which could sustain us, but in its unprocessed form is indigestible.

I am a second generation Taiwanese and Chinese American and the benefactor of two generations of my family’s immigration to the United States. My family owned a takeout retaurant in Kansas City in the 1990s, and this restaurant became the economic vehicle by which we pulled ourselves out of poverty. The takeout table, specifically, was a space of formative learning for me: where I learned to draw, read, observe people, and engage with the public. My first job was counting change to empty the cash register at closing time. My first business was selling 50 cent tins of tiger balm to customers waiting for their orders.

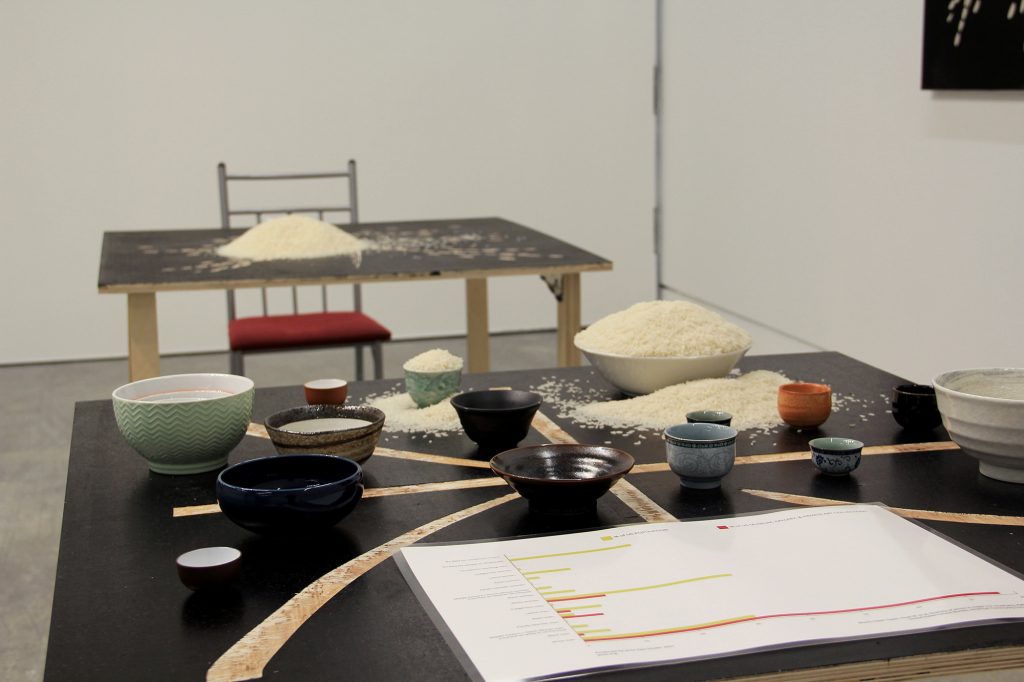

There are layers of removal, of diaspora, that take place within 米 mǐ.

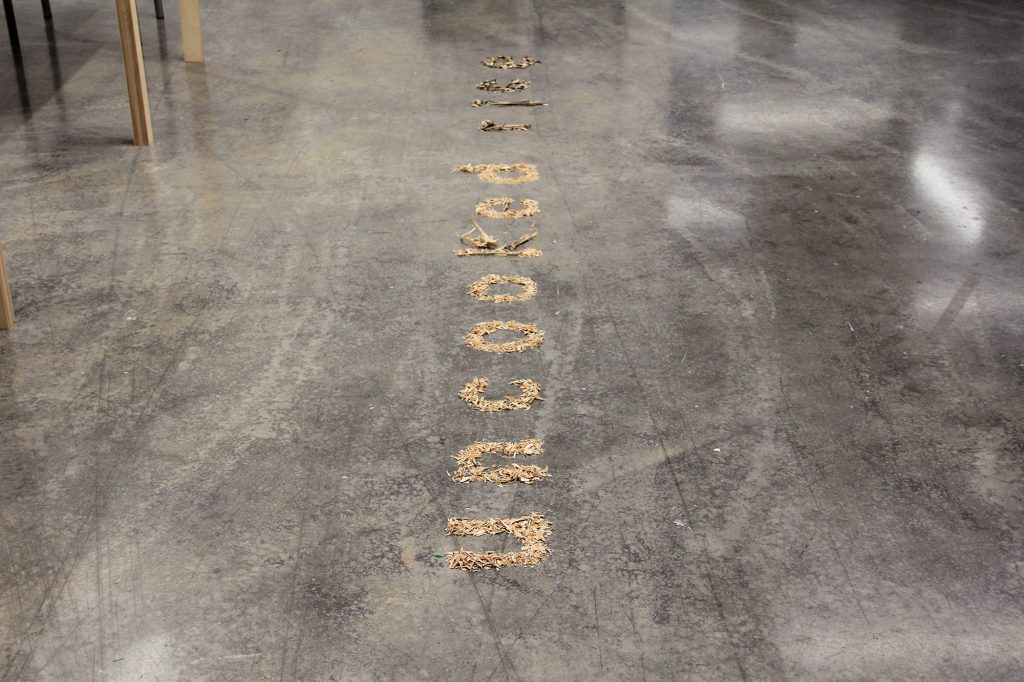

A drawing of a rice plant evolves into a pictograph before it becomes the modern Chinese character 米. Prints fade and language changes as we move farther from the source. Wood shavings form the English words, uncooked rice, the residue leftover from the carving and printing process.

A woodblock creates the print on canvas and the refuse on the floor, and is itself destroyed in its original purpose as a printing tool when transformed into a functional table.

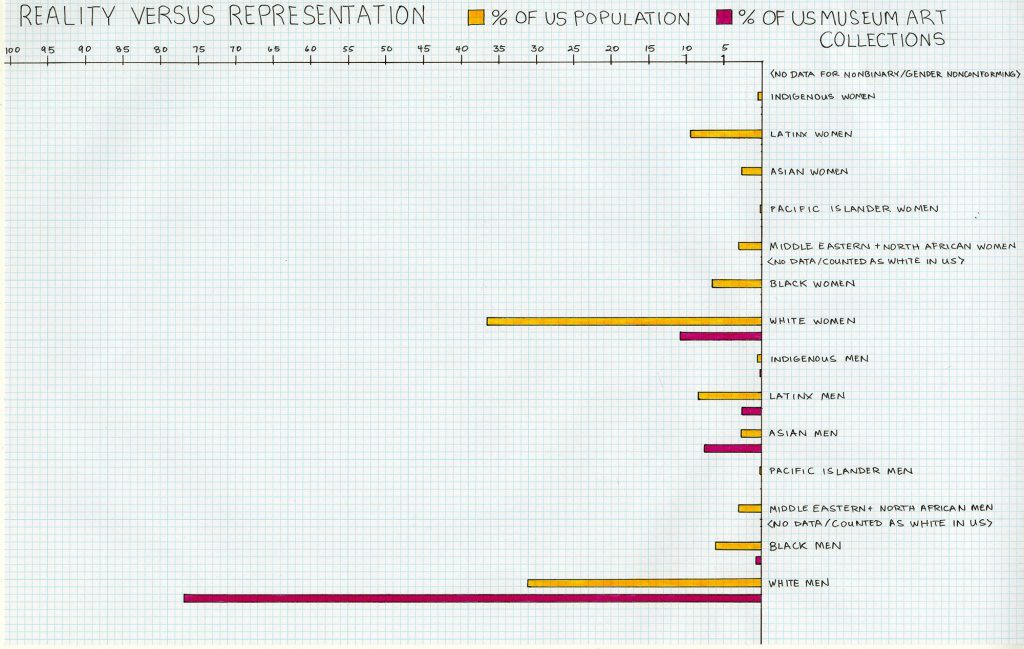

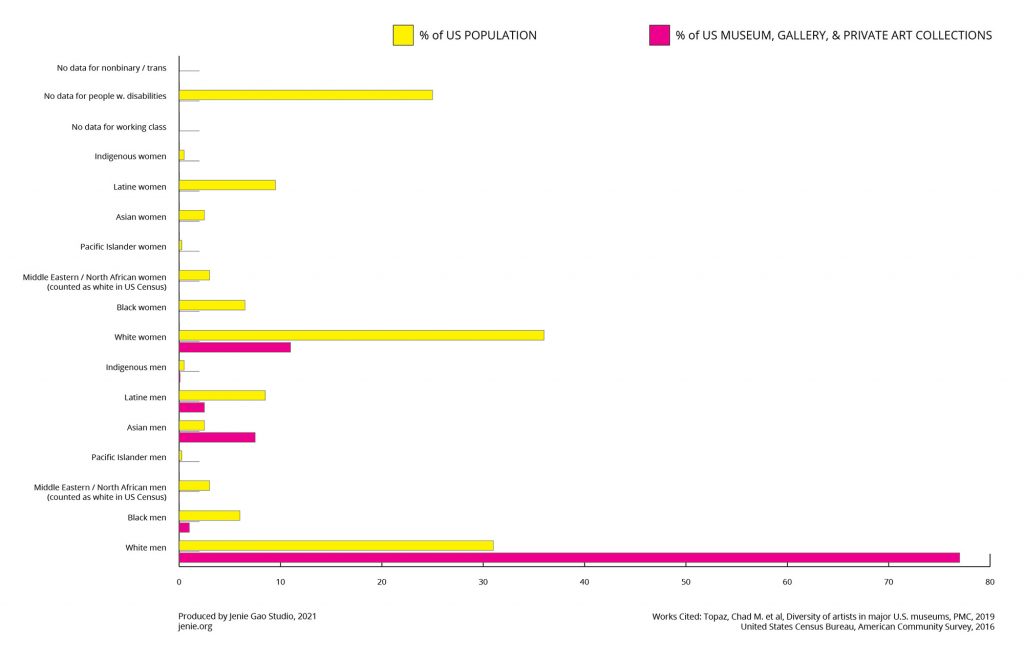

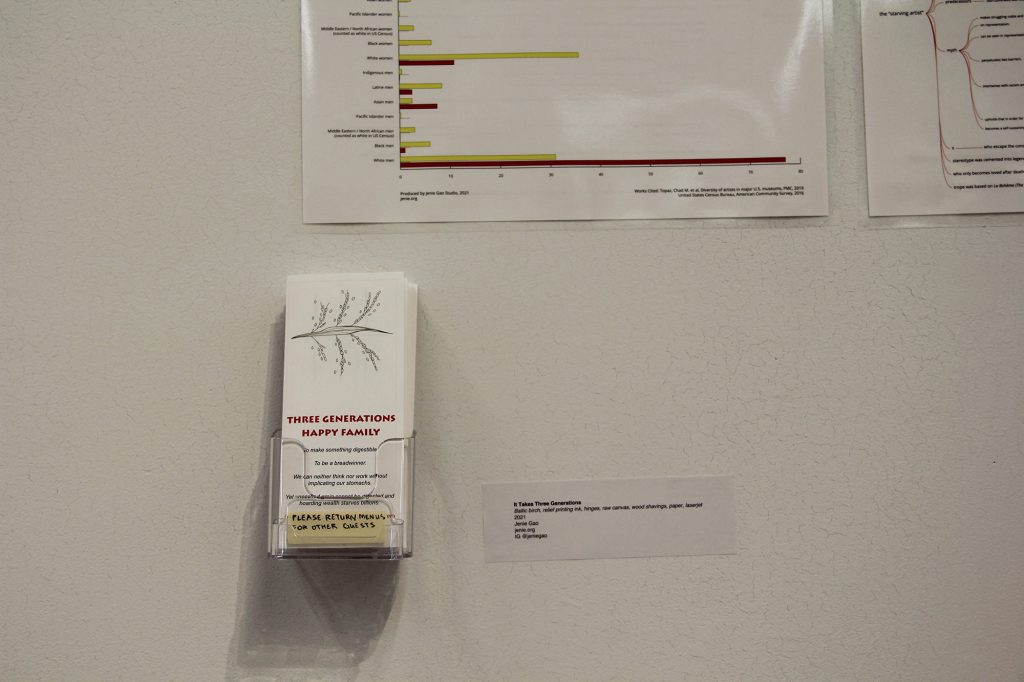

Data about who has representation in the art world unfolds to reveal personal stories that constitute the whole. A laminated placemat / menu displays US population percentages side-by-side with representation in US museums, galleries, and private art collections. Bowls on on table are either overflowing or under-filled, based on each population’s representation in the arts. For instance, while white men are 31% of the US (as represented by a 31 ounce bowl), their bowl overflows with 77% of the rice served on the table. Meanwhile, women of color collectively are less than half of one percent of US arts representation; their bowls contain only a couple grains of rice each.

A final, tri-fold menu unfolds to reveal a personal timeline, my family story told via food as a political and socioeconomic indicator.

The table is a place for gathering, and is also an altar to memory and grief. It feels necessary to have made space to remember and grieve what’s lost. For it is only after reckoning with how we got here that we can ask, what’s next for our future selves?

Photo credit Stefan Gibson