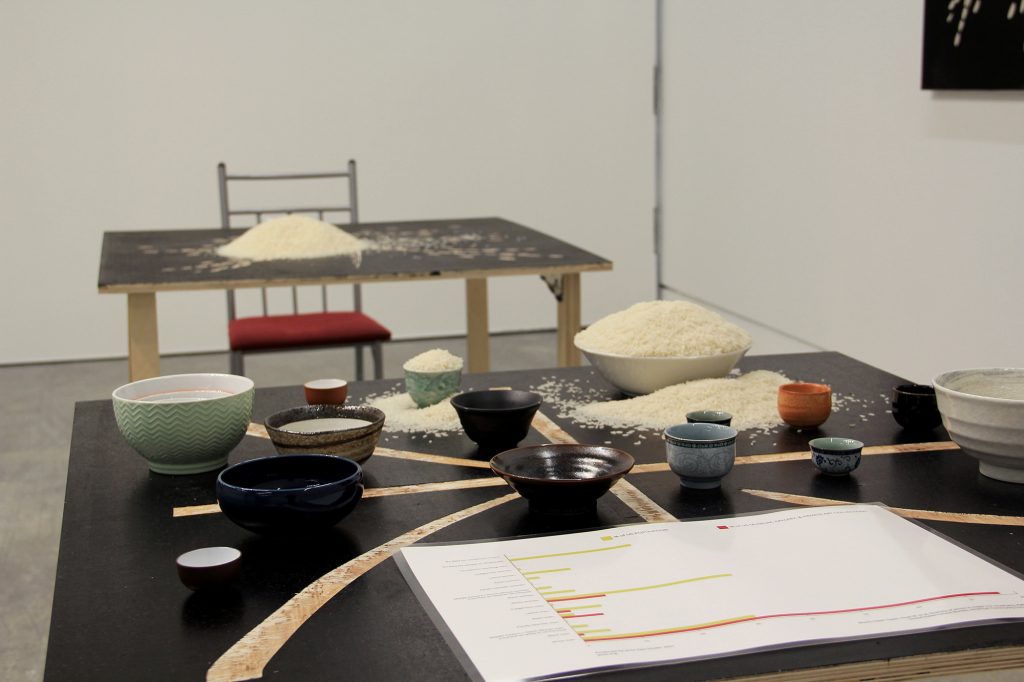

The Negotiation Table is the culminating body of work I have created during my time in the MFA. The following notes will walk you through the latest negotiation table I have created, which ruminates on cultural reclamation and transitions of power.

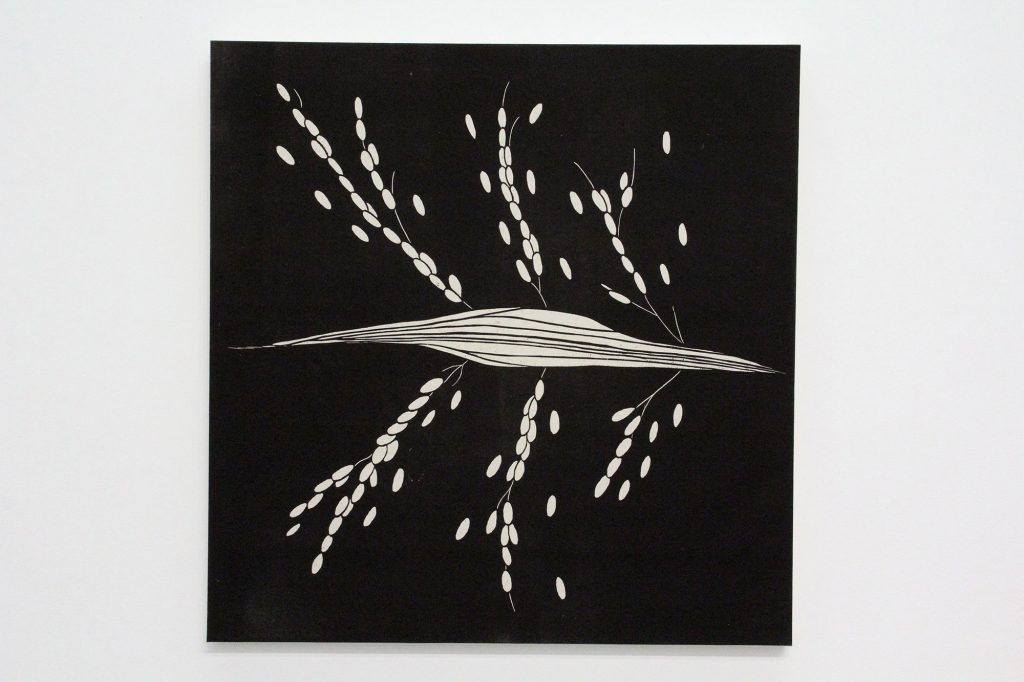

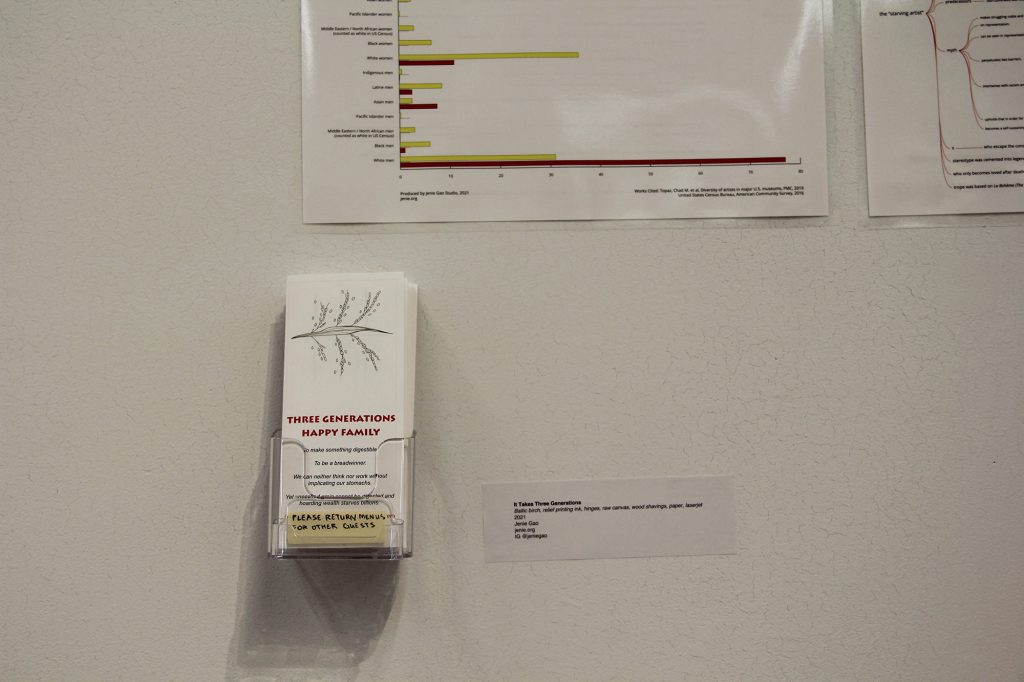

Printmaking and Diaspora: the Power of Repetition

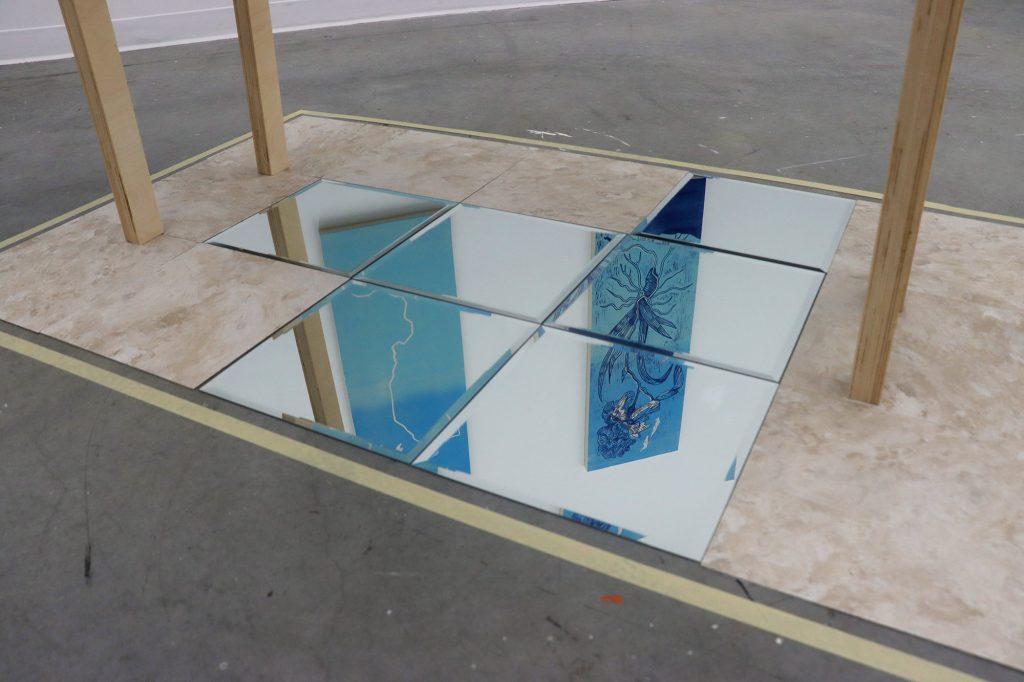

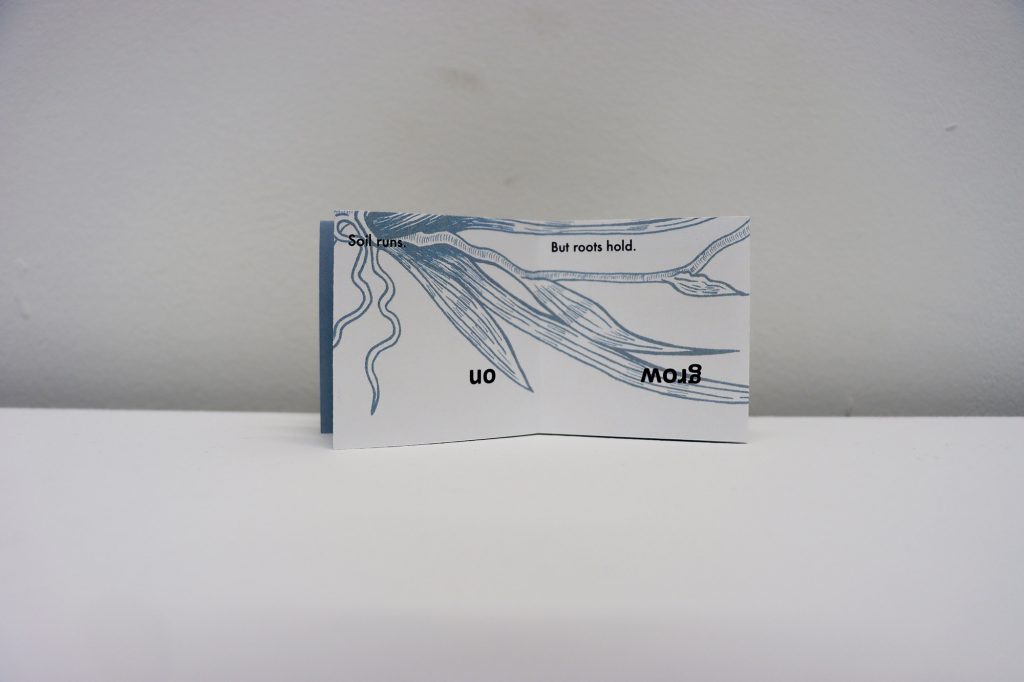

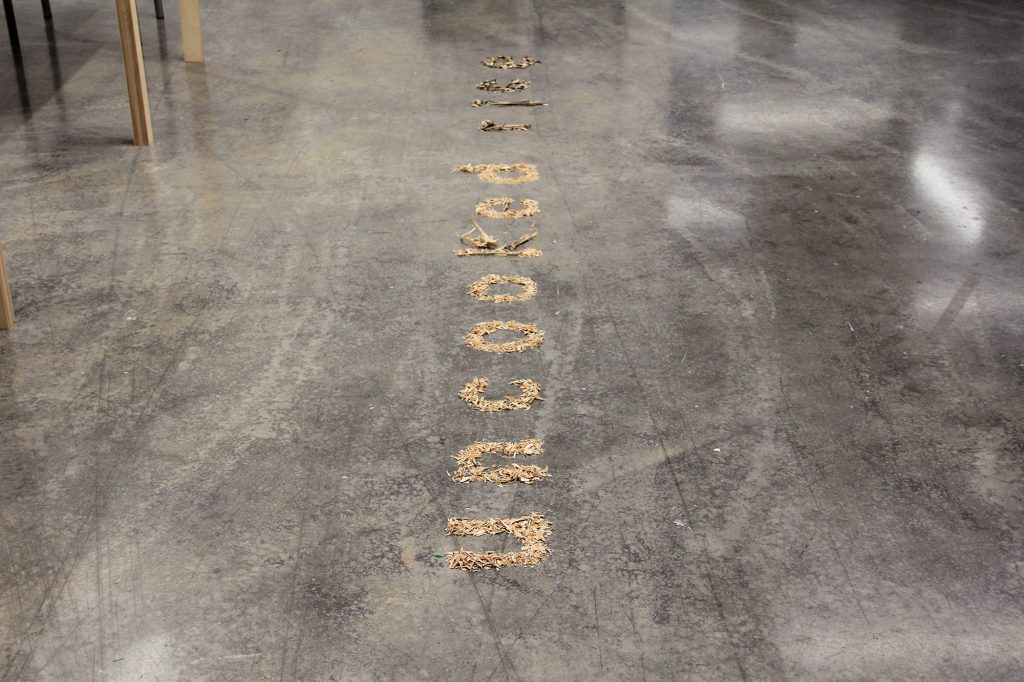

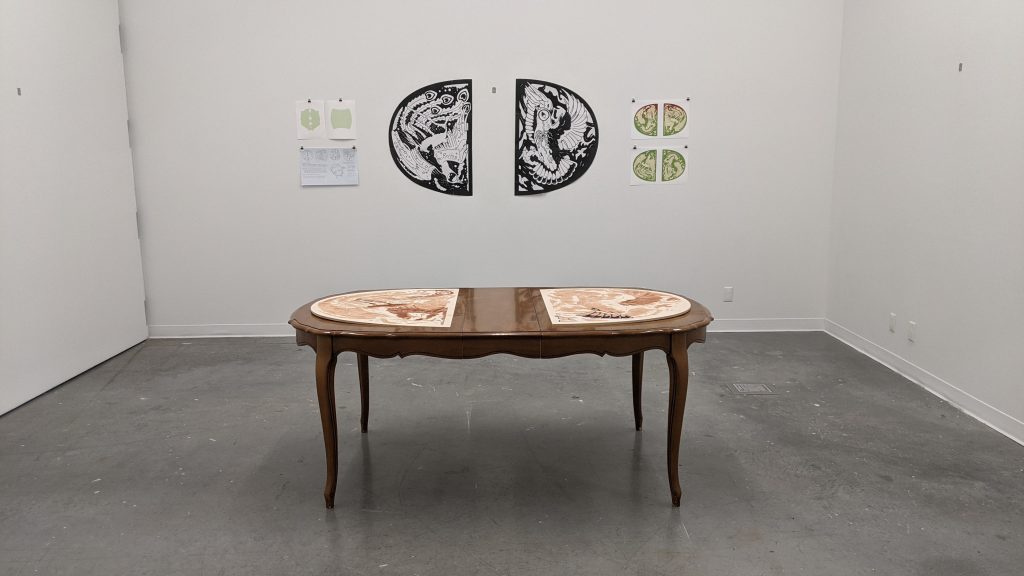

There are layers of removal, diaspora, and displacement in my printmaking methodology. From the woodblocks, I create prints and residual wood shavings. After finishing the prints, I transform the woodblocks into tables.

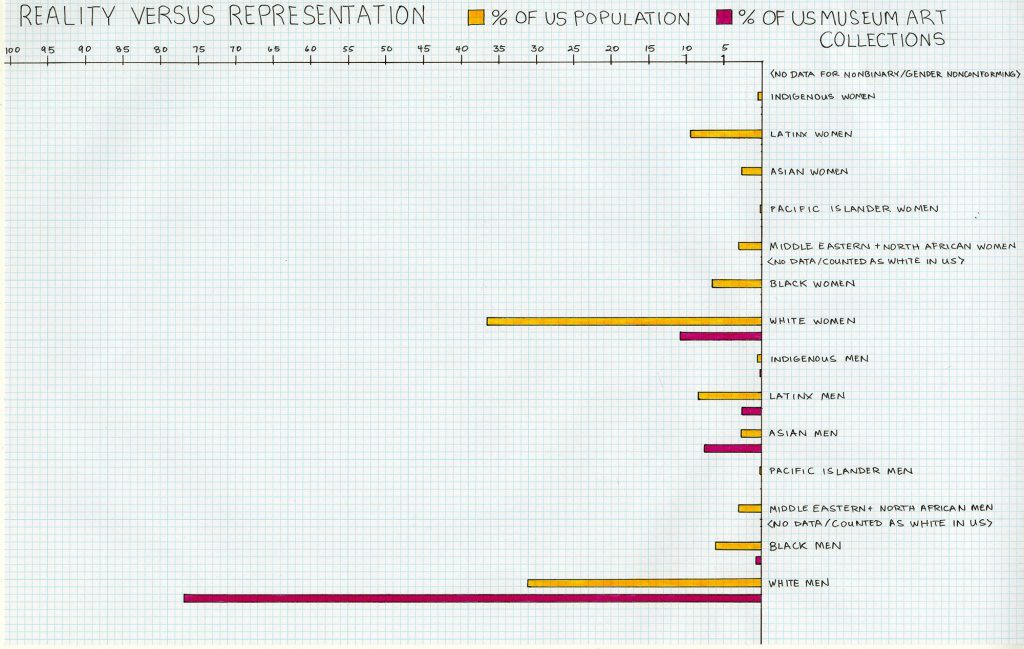

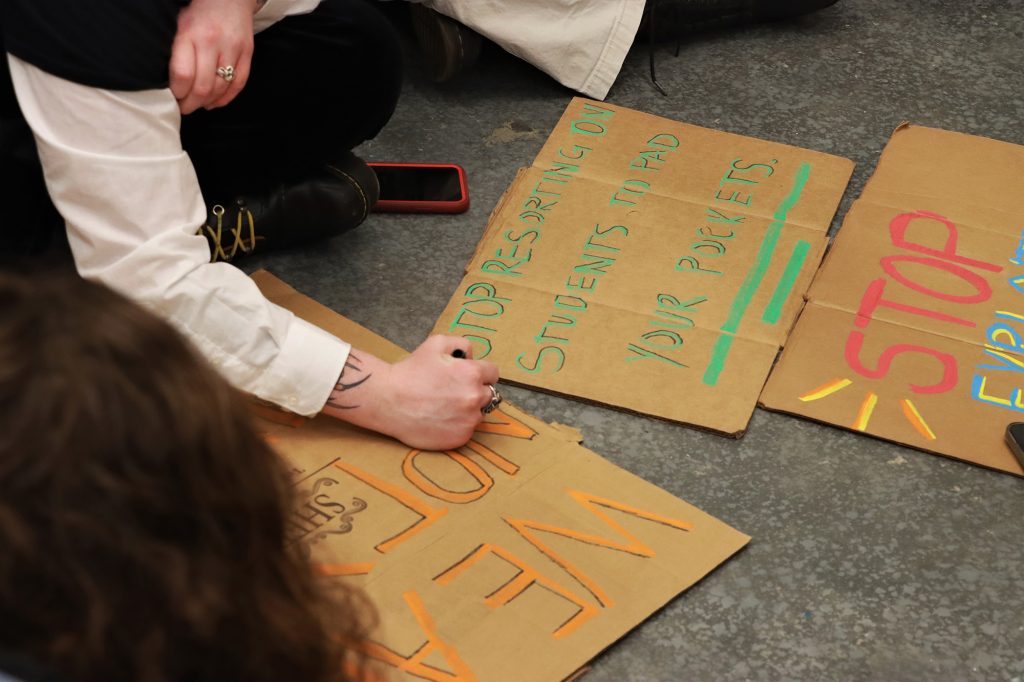

This transformation is in response to the history of how print became indoctrinated in the fine arts, in contrast to its use in political campaigning, protest, and community activation. Historically, print as an invention made it possible to democratize information and communicate with the masses. But to compete with painting, print needed to become artificially rare. It is best practice in printmaking to destroy one’s printing plates to limit the edition. I have always been uncomfortable with this practice of destroying one’s printing plates, or destroying any evidence of the actual labor that went into creating the prints. Working through this new methodology, I am reflecting on what it means for me to challenge print in this way, as an Asian American and woman of color who has been made artificially rare in white dominant spaces.

The strength of printmaking is in its power to reproduce the same message. There is power in the multiple and in the creation of new frameworks of comprehension.

I don’t number the prints pulled from these blocks, not because I wish to endlessly mass-produce them, but rather to give them agency from a predefined limit. So the limiting factor on the population of prints isn’t an artificially set quota, but rather the metamorphosis of the woodblock into the table and a new purpose.

About Negotiation

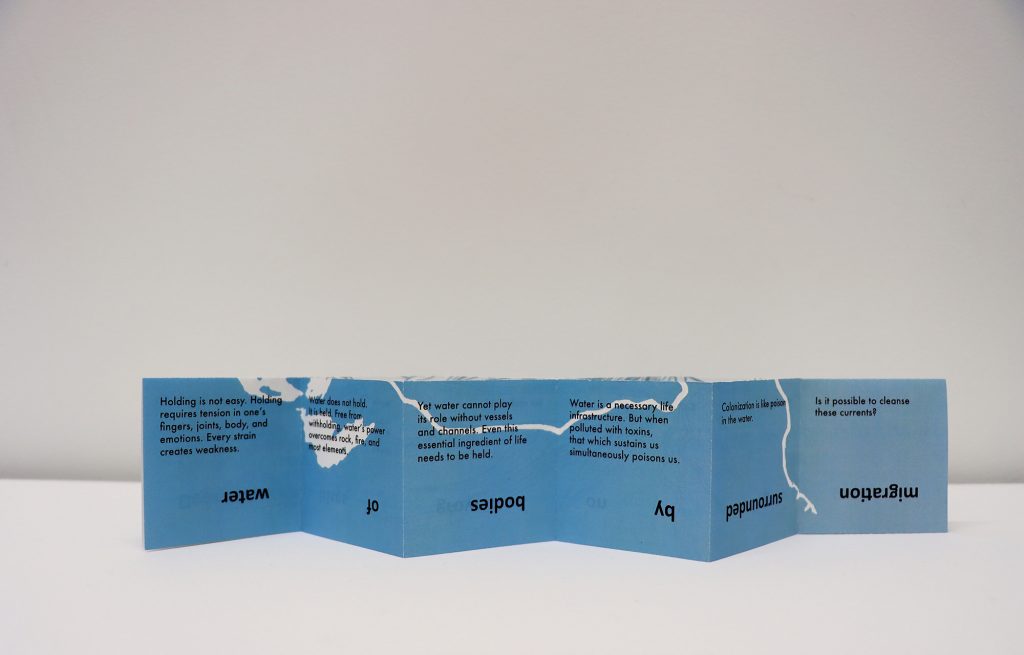

On the topic of negotiation, all good negotiations have a walkaway point. Without a walkaway point, one party will inevitably get taken advantage of. A negotiation, in essence, is between what you can and cannot accept.

Negotiations only work when the different parties each have something to gain. For the powerful, this can be as simple as a feeling of being appreciated. However, a problem arises when those with significant power must give something up, with nothing to gain in return, in order for the negotiation to be considered fair. Sometimes, the only corrective measure is to exit the negotiation.

For myself, I’ve had a public facing career for several years. Creating the negotiation tables has become a way to unfold the political to engage with the personal. It is an act of self-maintenance in the context of the institution.

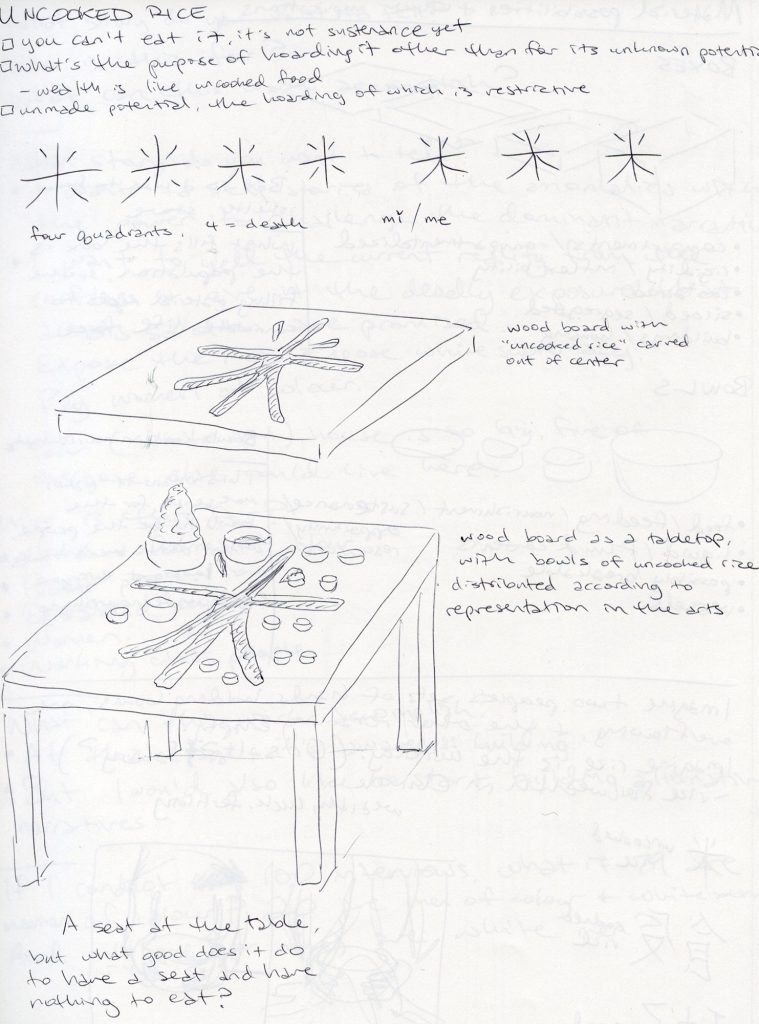

Preview of the newest Negotiation Table

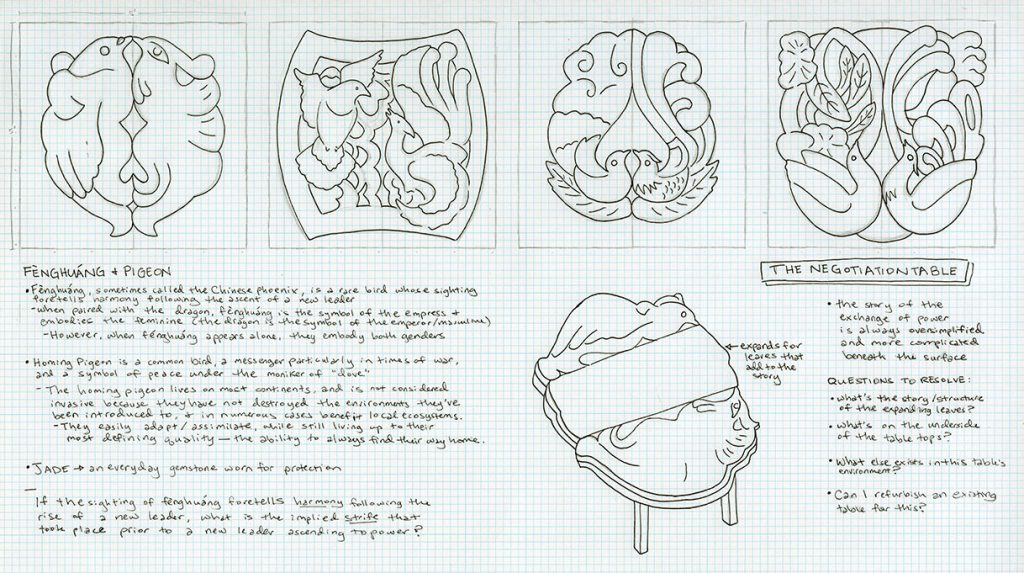

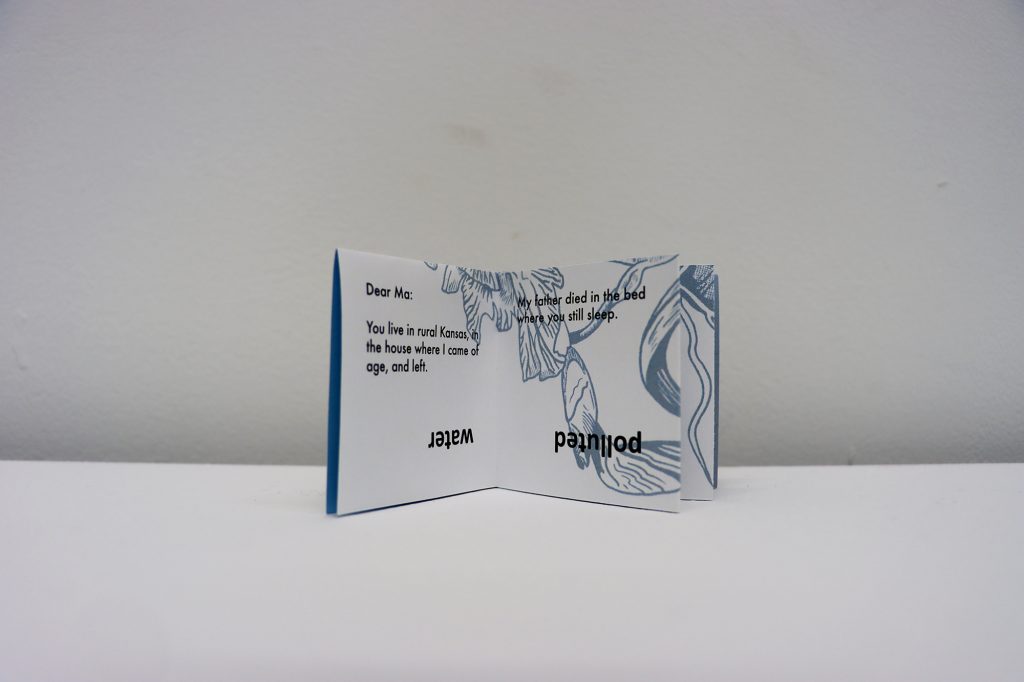

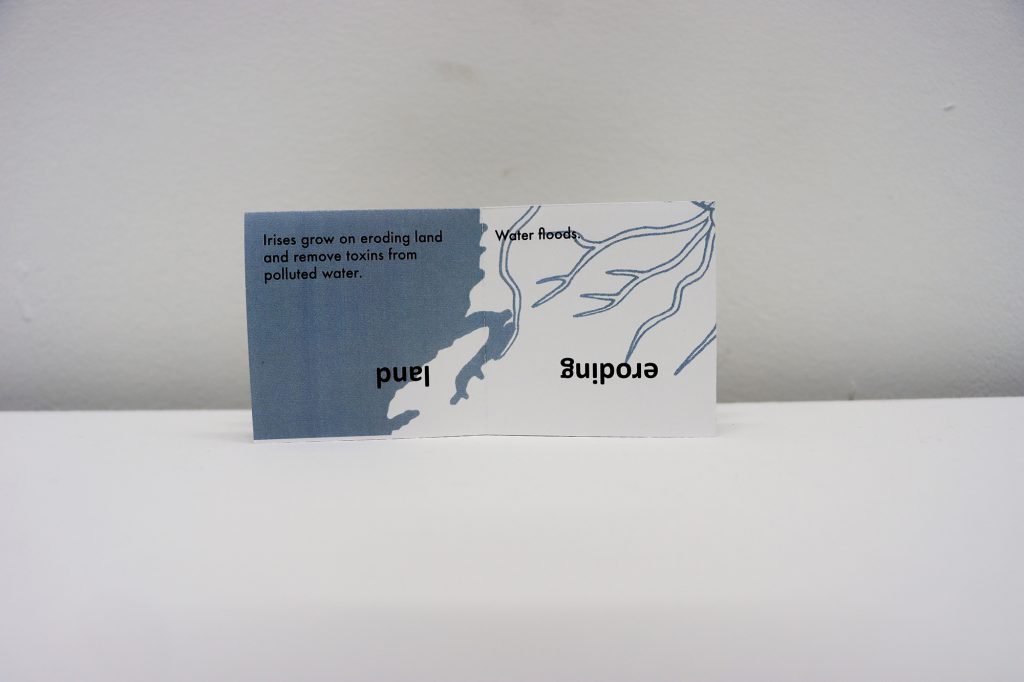

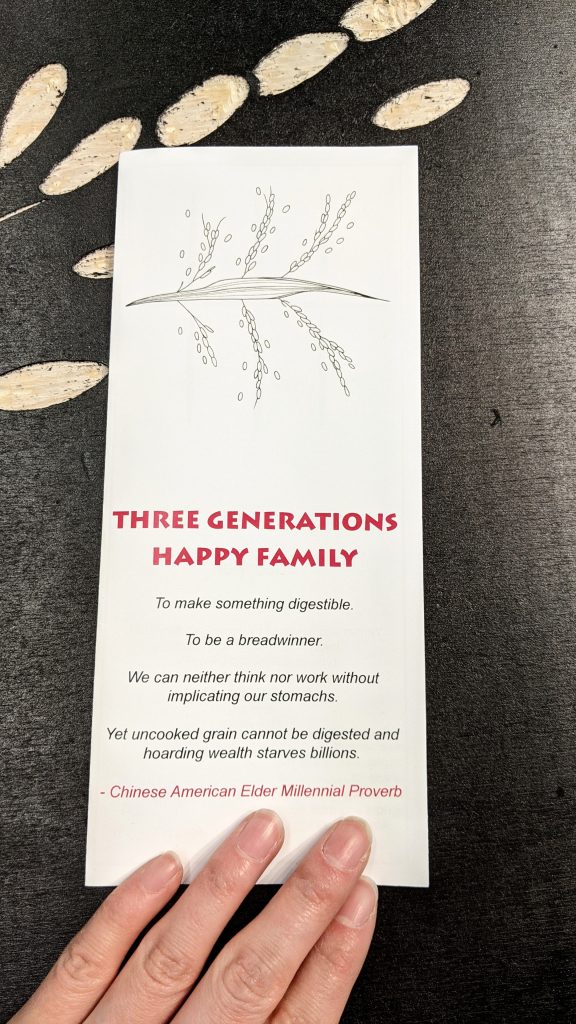

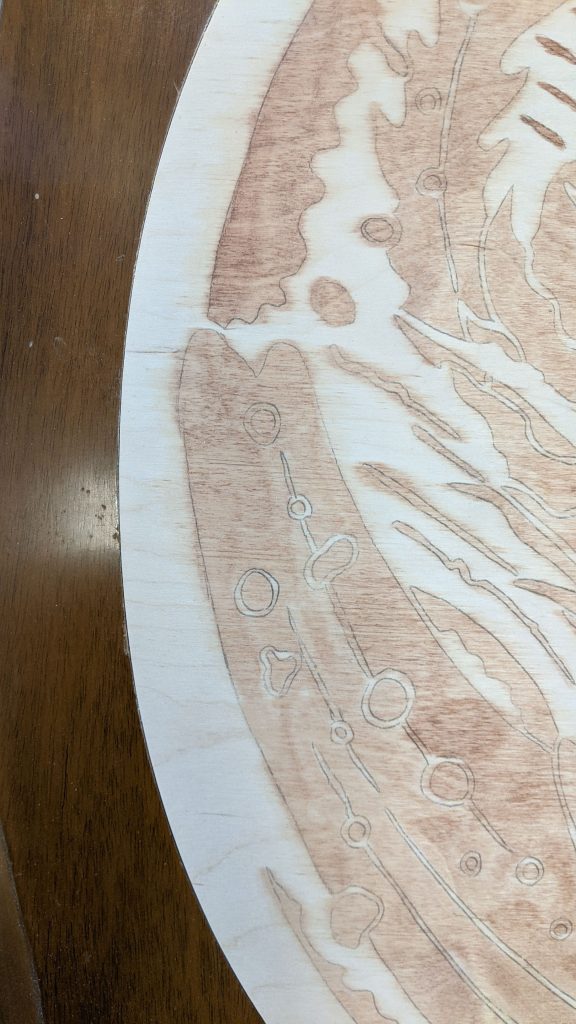

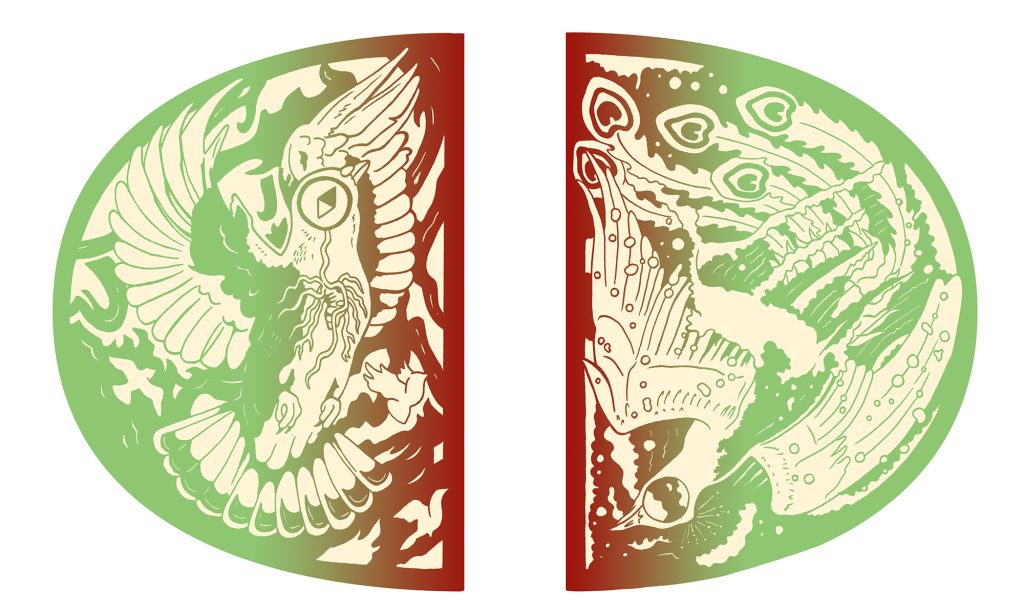

Similar to my previous works, there are two woodblocks. The images on these blocks are of two birds, a Homing Pigeon and Fènghuáng, also sometimes known as the Chinese Phoenix. The Fènghuáng is a mythological bird that sometimes represents the empress and the feminine, and at other times embodies both masculine and feminine power. The sighting of Fènghuáng foretells harmony following the rise of new leadership. The Homing Pigeon is a bird that I grew up raising a child, alongside my dad who first started raising them during the Cultural Revolution in China. For me, the pigeon has become a symbol of diaspora and class warfare. They are a messenger of peace in a warzone. They are highly adaptive, and yet no matter how far they go, they always know how to find their way home.

The woodblocks will be printed in a light jade green with a gradient to red towards the center where the images meet.

After I finish printing the blocks, they will rest in the surface of a reclaimed table. The blocks will sit flush inside the table and resemble inlaid jade.

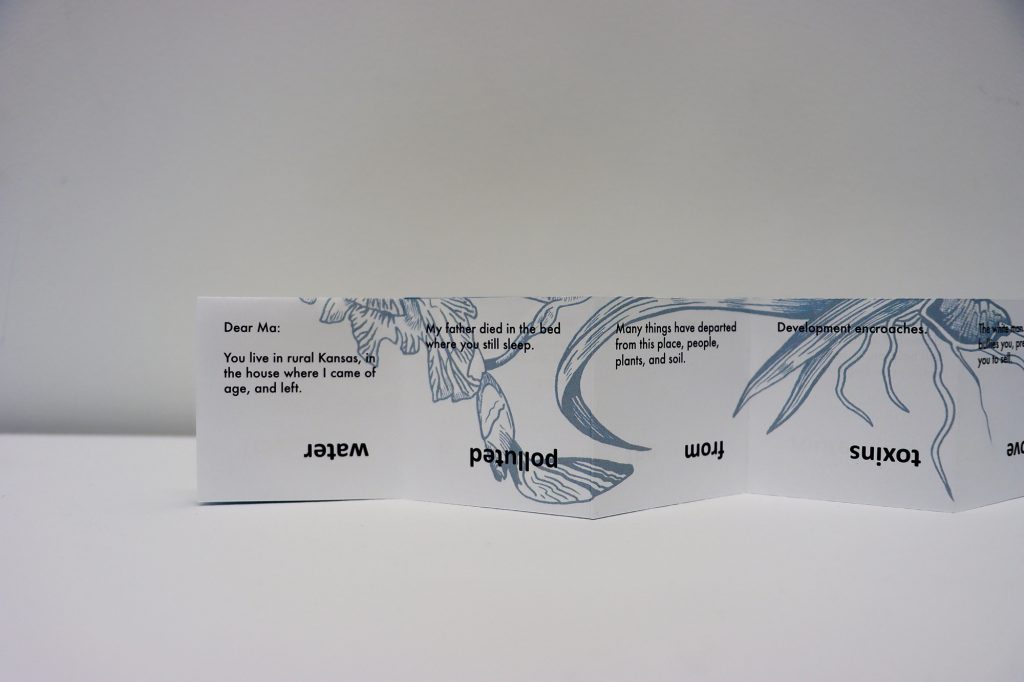

Cultural Reclamation

The table I’m reclaiming was made some time between 1953 and the early 1960s, so about a decade before quotas limiting Chinese immigration to the US and Canada were lifted. It is a Canadian made table, and has parts that were produced in the US, specifically Wisconsin, in a town halfway between Madison and Milwaukee, two cities where I used to live.

The design of the table is a knock-off of Rococo and Chippendale furniture styles, which gained popularity in Europe and the US colonies starting in the 1700s with the rise of Orientalism and British occupation in China. The Rococo and Chippendale styles appropriated heavily from Ming and Tang-dynasty furniture that Europeans looted during China’s Century of Humiliation.

In essence, I am cutting into this knock-off of a knock-off table as an act of reclamation and resistance to assimilation. I am making an indelible mark to keep the history of diaspora in the public’s living memory. Accountability takes a long time to achieve. The function of oppression is to wear people down and make them forget so they cannot fight anymore. But by creating a record, remembering becomes a key function in long-term justice.