An Ethic is A Root is an exhibition that summarizes my spring semester work and first year of the MFA. It navigates the question of how we arrive at our ethics. What are the potential costs of our ethics? What are the gains of upholding them?

An Ethic is A Root explores questions of ethics and equity. I use personal, lived experience as an entry point to engaging with systemic and socio-political issues. From my hand-carved woodblocks, I build tables and installations that become negotiation spaces for cultural authorship.

The central image in this series is a map of my migration route, from where I was born in Kansas City to each of my homes in the Midwest of the United States to my current home in Vancouver, British Columbia. This map becomes an infrastructure for a greater story of removal, diaspora, and rootedness.

My mother still resides in my last childhood home in rural Kansas. It is an older house attached to a few acres of land. This land was once lush and green, full of fruit trees and a vibrant ecosystem. This same land now sits mostly barren. The trees are gone. The ponds are gone. Agricultural runoff and nearby development have made the soil poor. The land around my mother’s house regularly erodes and floods when it rains. Yet the iris flower continues to consistently grow here. Irises are known for growing in places with polluted water, effectively removing toxins and holding soil.

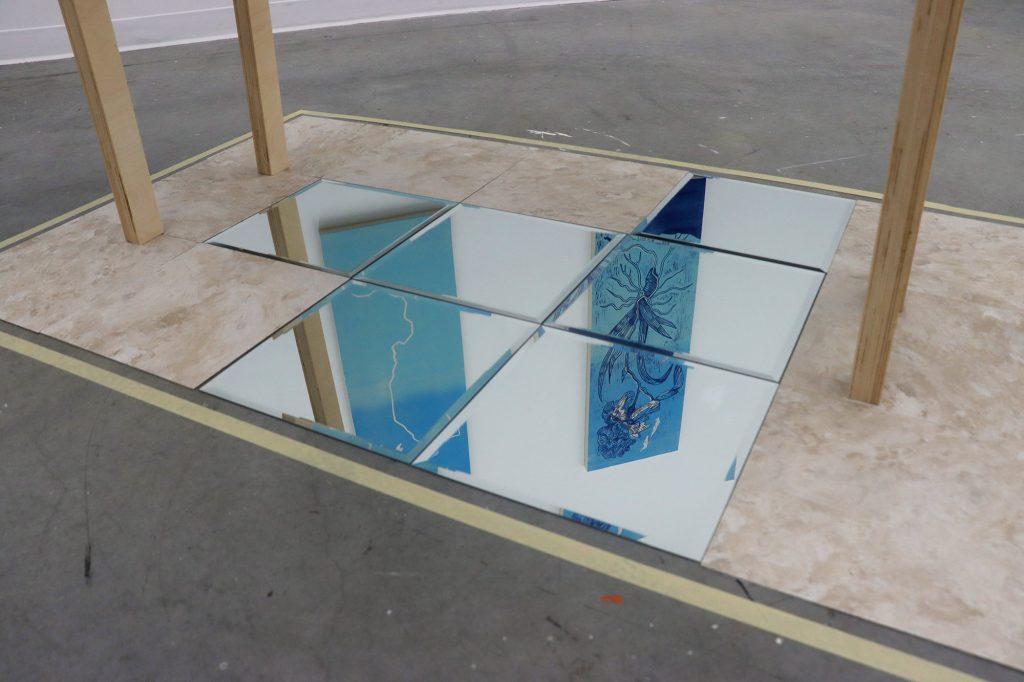

Two elongated tables stand at the center of this installation, framed on one side by an altar to my deceased father and on the other by a table of artist’s books addressed to my mother. Each table is its own structure, yet bears a cut edge that matches the other. One table is made from the two-sided woodblock that produced the prints. The other table bears no image of its own, but provides a surface for the residual wood shavings forming the characters of my name in Chinese. Repetition, reflection, and rumination are prominent in this work.

Working through this methodology, I reflect on what it means to challenge cultural assimilation, in print, and as an Asian American and woman of colour who has also been made artificially rare in white dominant spaces. In printmaking, the strength of the technology is in its power to reproduce the same message. Yet this is seen as a weakness in the fine arts, a redundancy that makes prints lose value and exclusivity. How often are marginalized people made to feel like broken records, asking for the same, basic rights? How often are we made to feel that we have to compete against the few other BIPOC and femmes in institutions, as if we can’t be valuable if there’s more than one of us? Is what we are saying it truly redundant if we are still waiting for action and reconciliation?

There is power in the multiple and in the creation of new frameworks of comprehension. There is strength in our reflections and in pursuing legibility of lived experience. This work is for anyone who has ever doubted their strength against the odds that they face, yet has held on anyway, and found their conviction in the process.