Reflections on the Medicine Wheel Ceremony at VanDusen on the 2022 Summer solstice (June 21st)

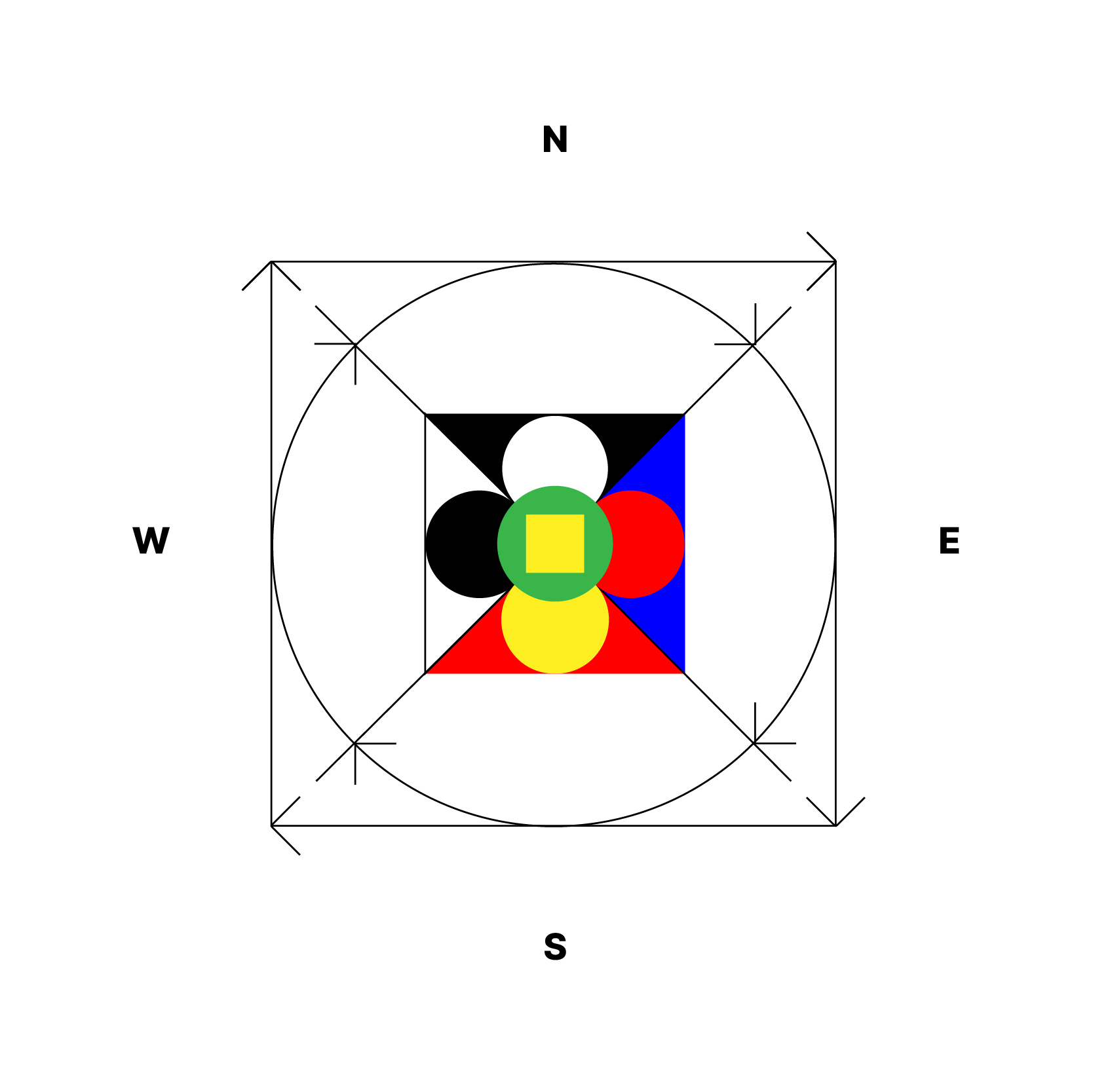

The medicine wheel (also called the Sun Dance Circle or Sacred Hoop) is an ancient and sacred symbol widely practised by first nations people in North America. It represents balanced and peaceful relationships between humans and non-humans, holding rich meanings in the four cardinal directions, stages of human life, seasons, animals and plants for healing and harmonious well-being. When I heard about this ceremony of celebrating solstice at VanDusen, I was excited to learn and experience such a rich spiritual ceremony and embedded teachings in person.

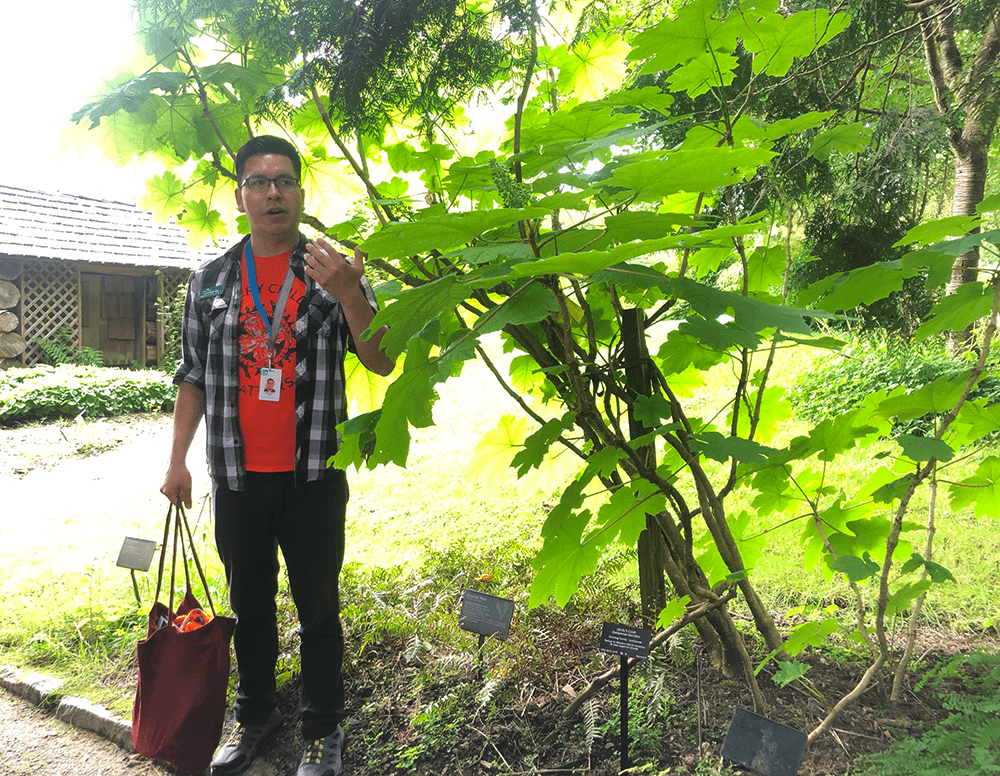

After taking time to cleanse our bodies and minds with the smoke of burning sage, the ceremony began with singing and drumming. Elder Phil L’Hirondelle, who led the ceremony, invited us to close our eyes and think for a moment about the creatures, four-legged, two-legged, plants, food and rocks that surround us.

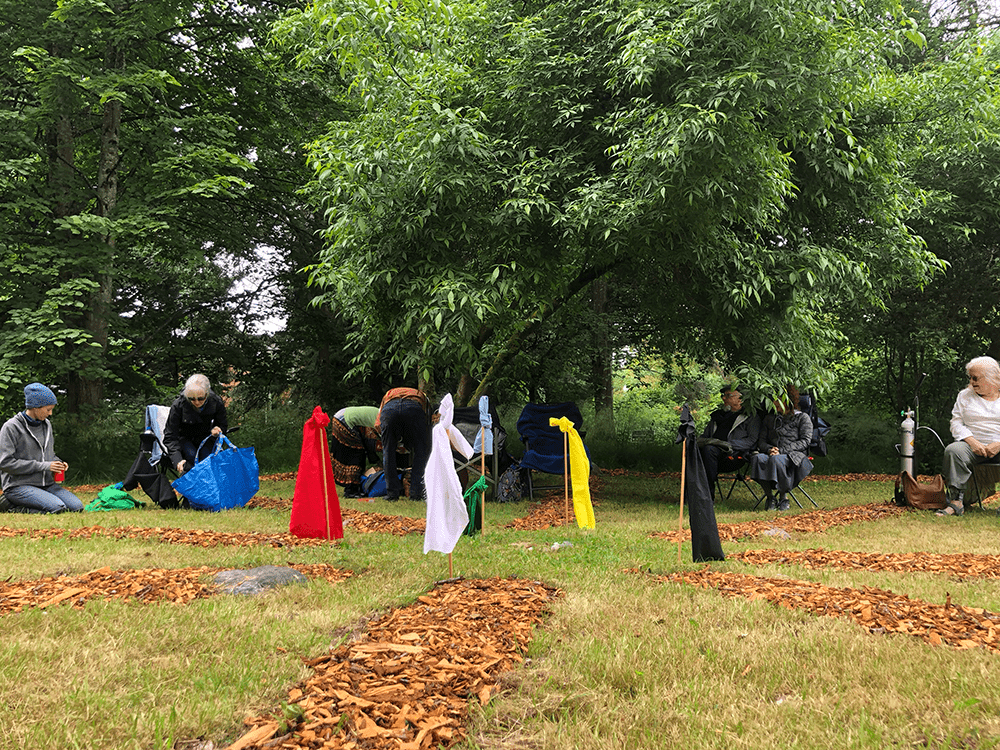

Sitting around the circle side by side with whom I had just met along the big rim of the medicine wheel, we together listened to prayers and oral teachings of the medicine wheel.

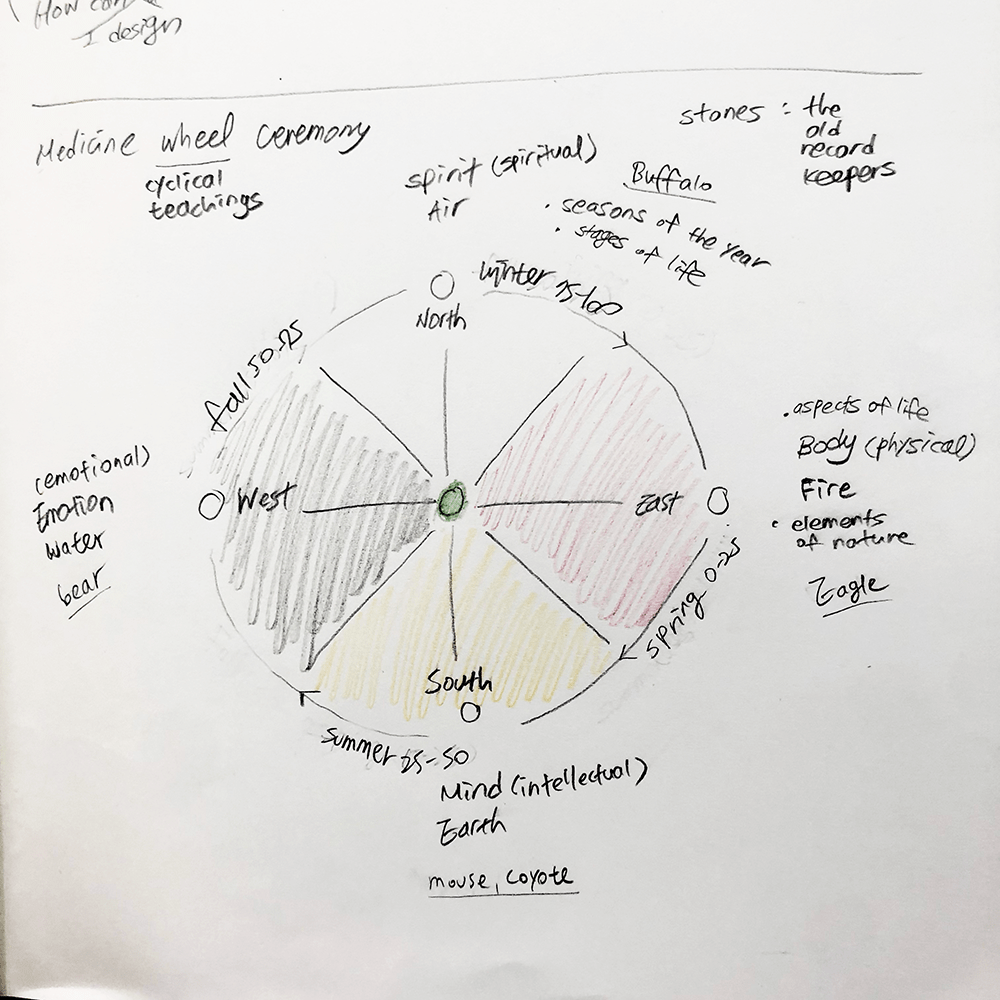

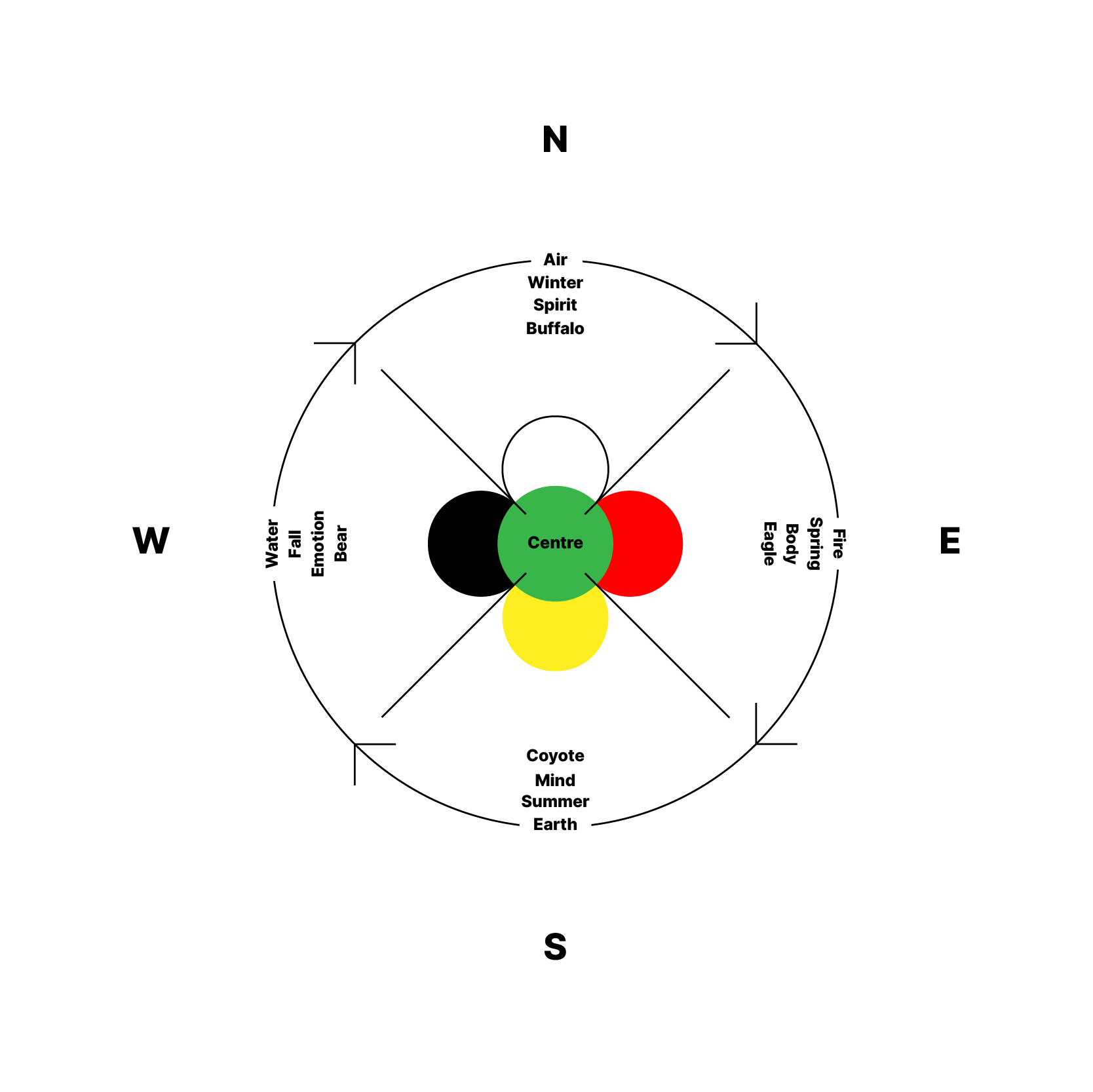

Each colourful flag represents the cardinal directions, seasons in nature, stages and aspects of human life. Although there is a difference between region and tribe, medicine wheels correspond to such meanings below.

- Yellow South / Mind / Spring / Age of 0-25 / Mouse

- Black West / Emotion / Summer / Age of 25-50 / Bear

- White North / Spirit / Fall / Age of 50-75 / Buffalo

- Red East / Body / Winter / Age of 75-100 / Eagle

Seasons of the year and stages of life

Listening to the rich meanings of each quadrant of the wheel, I was able to learn the cyclical perspective of our lived experience, our time experience as humans. Based on one of the elders’ teaching, thinking through the seasons of human life gives us a sense of perspective that what you will get by fall and winter time depends on what you planted in spring, in the earlier stage of your life.

I came to understand what this wheel asks us to do is the connection with our past, present, and future selves, the spiritual world and the earth concerning holistic health. Co-relationships of body, mind, emotion and strengths of other beings taught me the importance of harmony and cycles of living that are removed in quantified, measured, instant scales of time.

Participation

As the important part of the medicine wheel ceremony, participants were asked to bring a stone to infuse their prayers and leave it in the centre of the wheel, on the earth. At each turn, a group of four people stood in each of the four directions and introduced themselves with their ancestry roots. Hearing precious and sometimes heartbreaking stories and prayers from different ages, life experiences, and ethnic groups was a powerful and intimate gathering I had never experienced.

We ended the ceremony, again standing closely in cardinal directions representing each of our age groups who I had just shared intimate two hours with. There was so much value and depth in these native teachings that left me feeling of gratitude and appreciation. The gifts that were given were; the harmony that comes from connectedness, healing from deep listening and seeing a full circle of life stages among each other. If this framework of worldview was practiced at schools and workplaces, what would happen?

+ The medicine wheel graphic

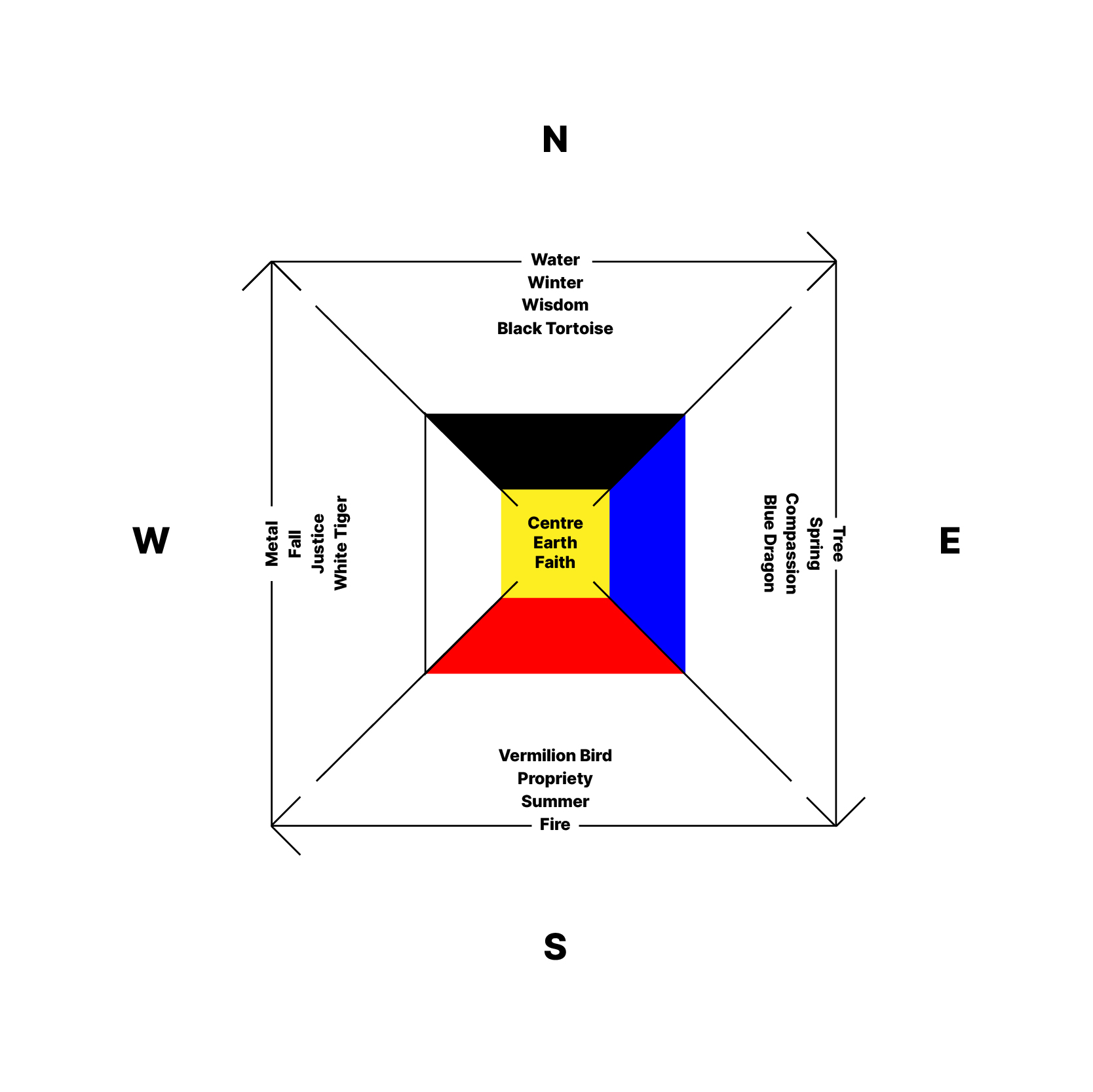

+ 오방색 O-bang-saek (Five elements of colours) graphic: The traditional Korean colour spectrum

+ Combined graphic (because they are way too similar)