Observing other-than-humans in Vancouver #1. Daddy longlegs spiders

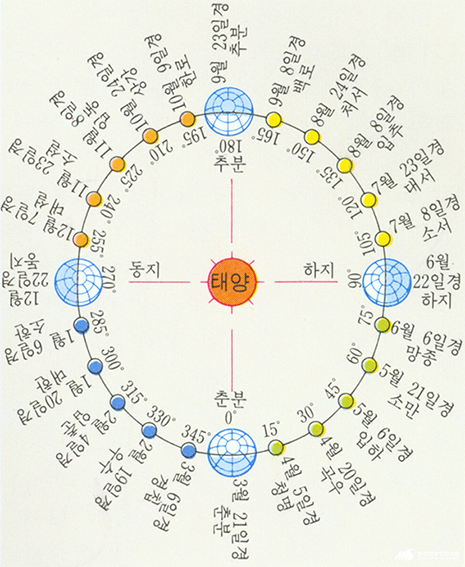

This project started from my curiosity about other-than-human rhythms and cycles of time that are no longer being paid attention to and don’t matter in this modern world. I grew up in Korea speaking the language which has numerous idioms and proverbs of ecological wisdom, especially to guess the climate and weather for farming; “if swallows fly low, it rains.”, “If nests of magpies are built low, typhoons will occur frequently.”, “When the starlight shakes, it’s a sign of a strong wind.” When thinking about my mother tongue, I sense a piece of strong evidence that my ancestors read complicated cycles of nature to thrive within nature. My ancestors believed we can communicate with and learn from nature if we know how to listen. And I think it’s similar in a lot of other cultures too.

My dad has an enormous amount of ecological knowledge that I’m envious of. But I shouldn’t use the word envy since it wasn’t really his choice to learn. He was born in 1961, 8 years after the Korean war. He was raised in a rural mountainous town in Korea, and it was his obligation to be responsible for what to bring to the table each day. Thanks to the ecological knowledge that shaped my dad’s childhood, I also grew up eating fresh herbs and roots he foraged from his treasure house, mountains. Pondering my projects around plural perceptions of time, I started thinking about what will happen once my dad passes away. When my dad’s generation time ends, what will happen to their knowledge that was only could be learned during the era they lived, which can’t be mimicked anymore? In Vancouver, 2022, can we still practice living the way my dad once lived, having rich conversations with nature? Can I still speak the language my ancestors used to listen to what nature has to say?

Observation and record as a method

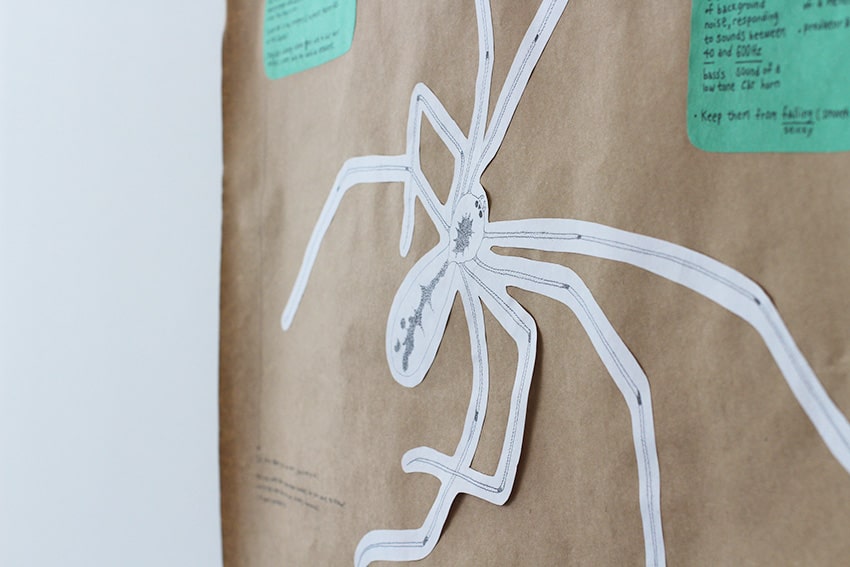

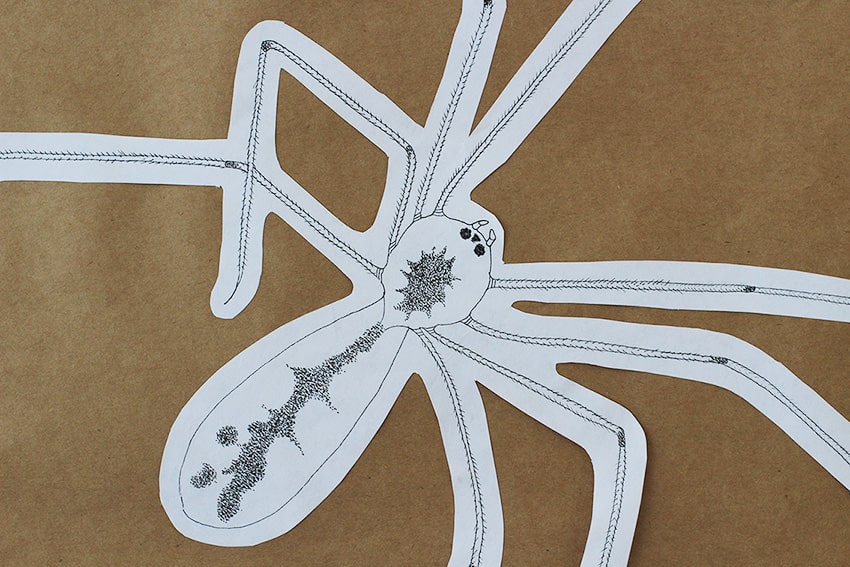

I wanted to go to a specific park or lake frequently to observe what is happening in the non-human world every day, to be able to have a peek at their perceptions of time through my limited human sense of time. However, due to a recent swamp of deliverables, I spent a lot of time in my room, and therefore, the spiders in the corner of my ceiling became my first non-human to observe.

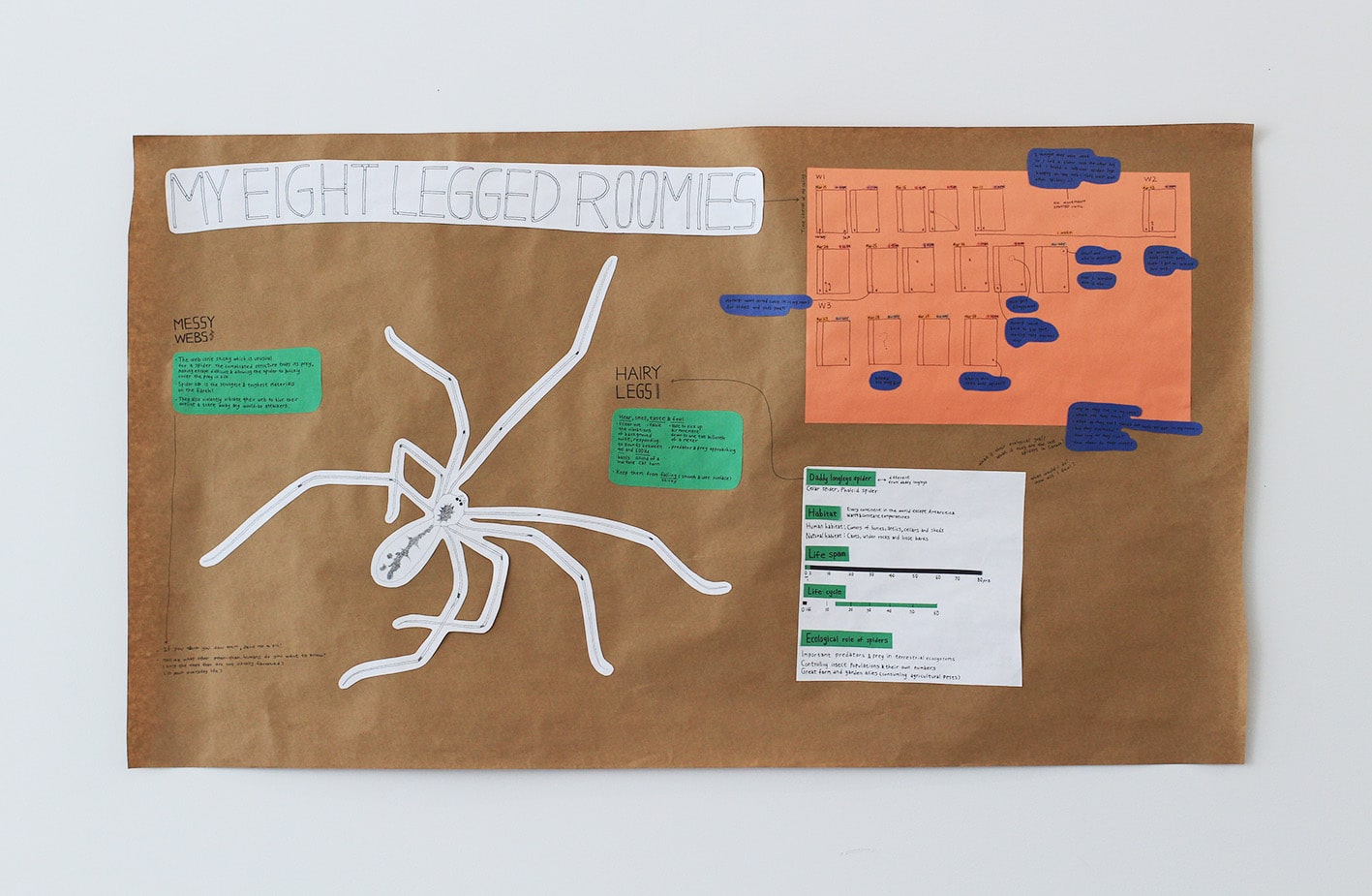

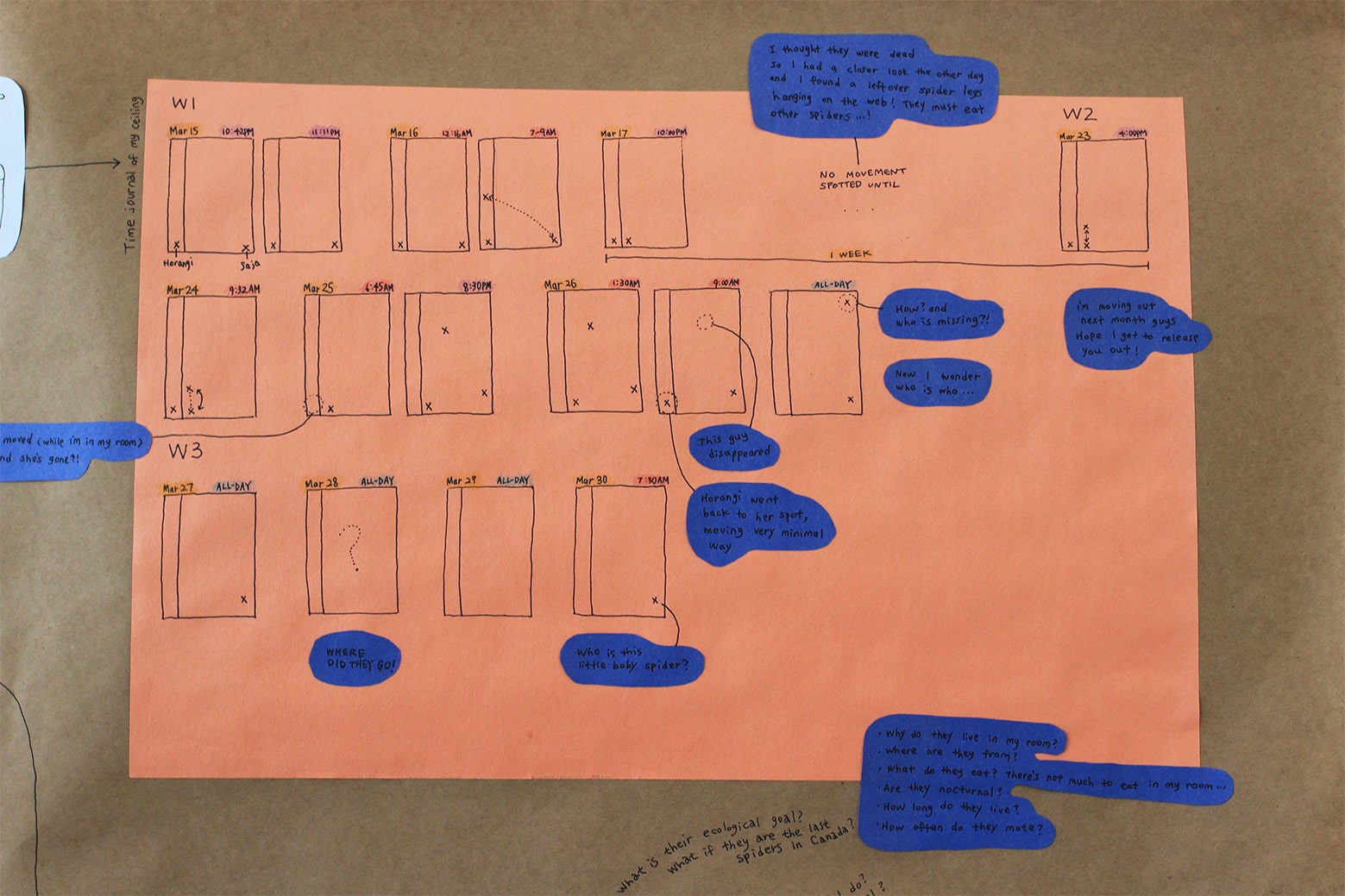

1. 2 Weeks time journal of the spiders on my ceiling

From March 15 to 30

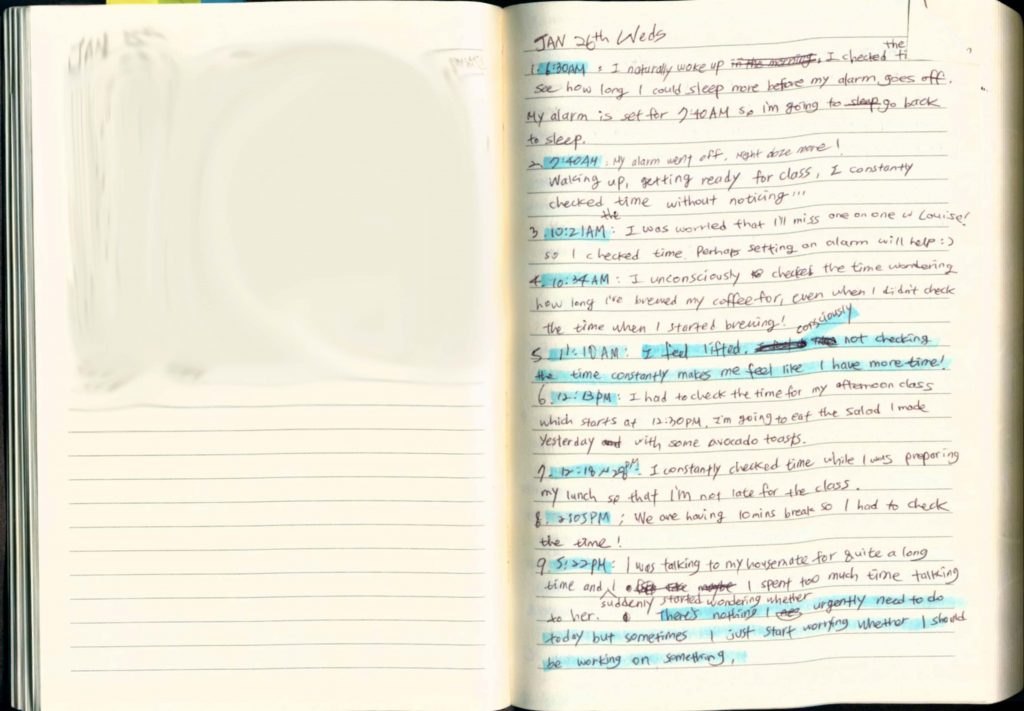

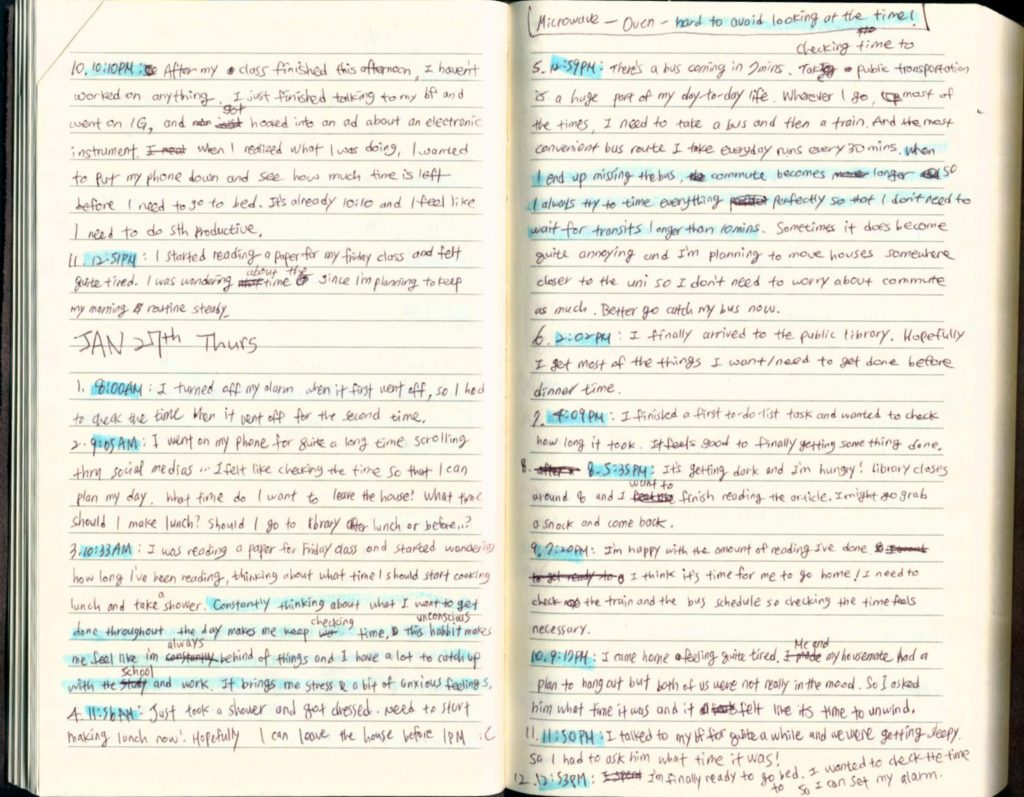

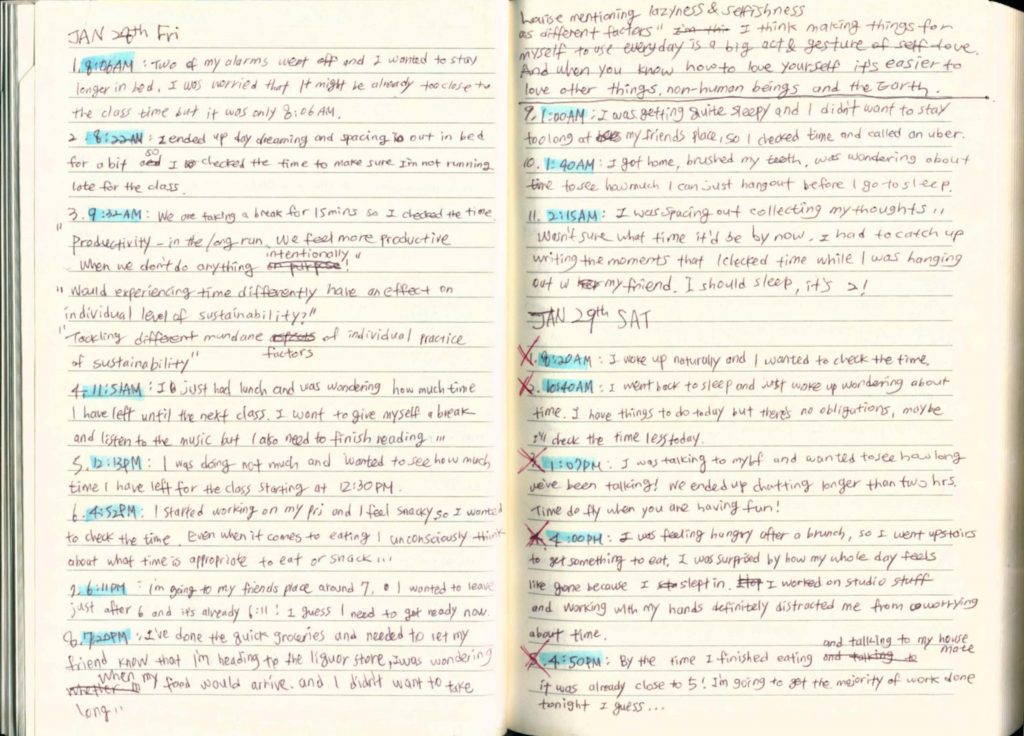

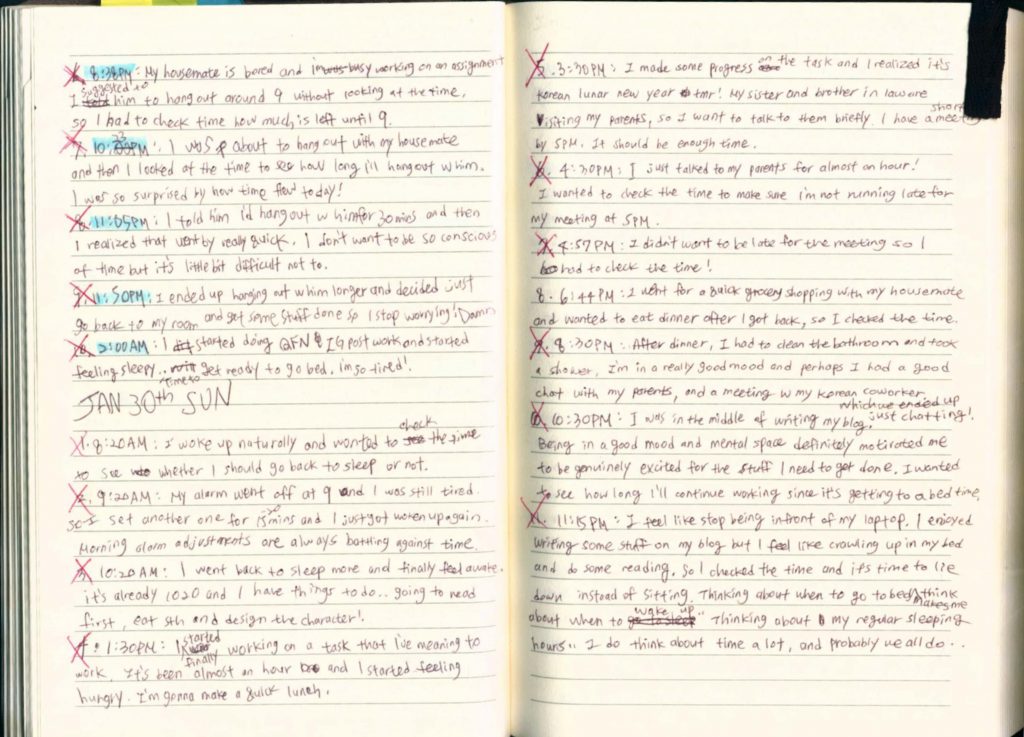

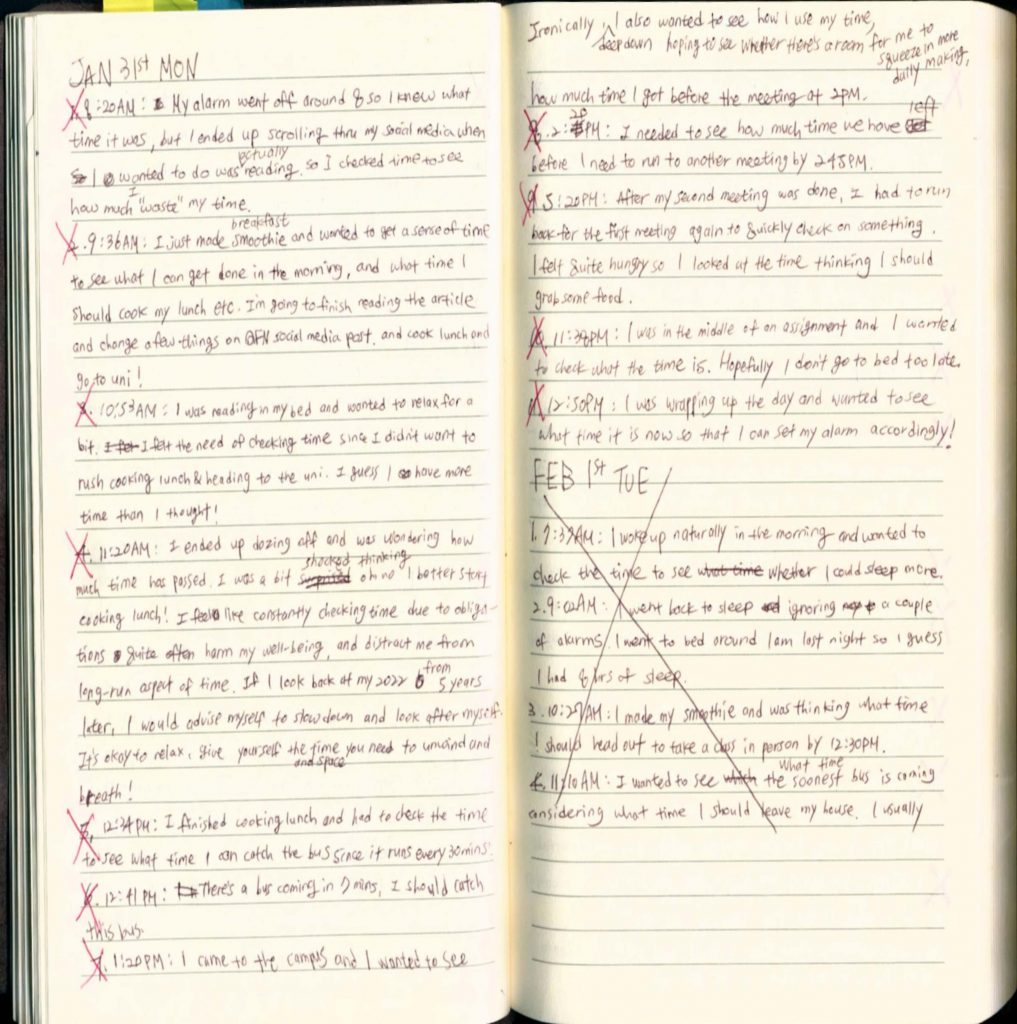

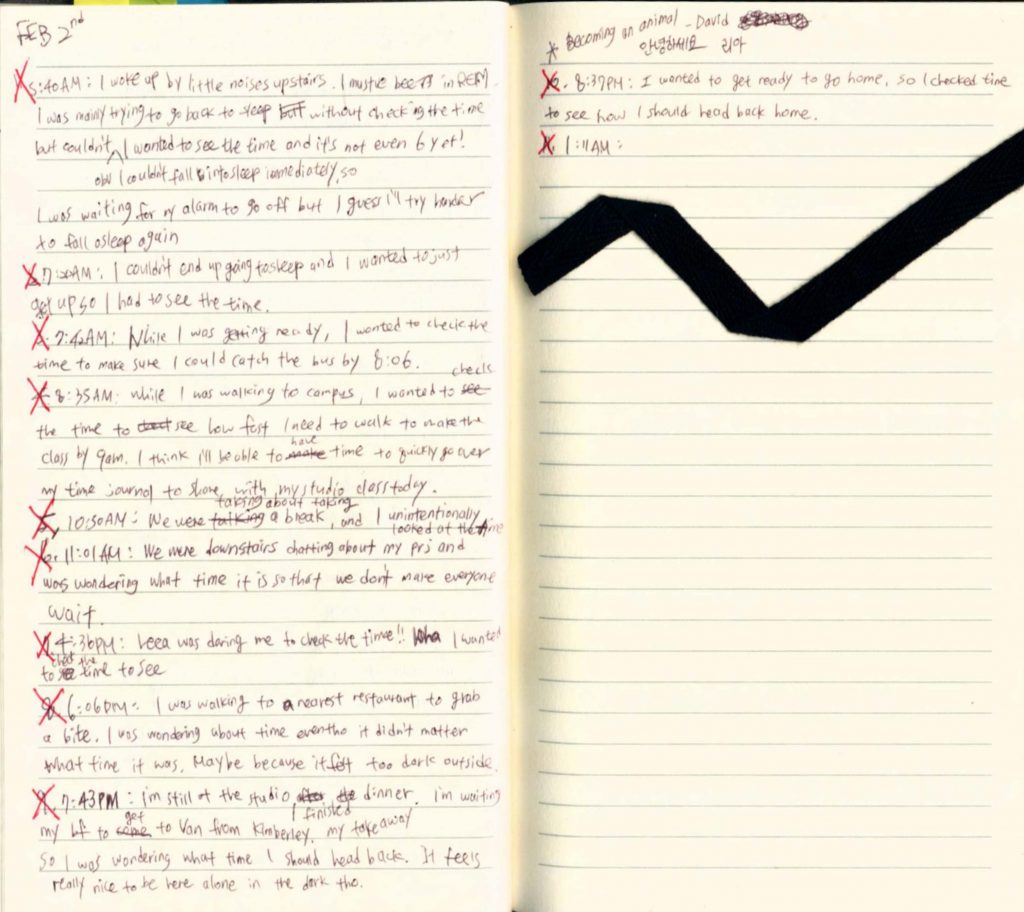

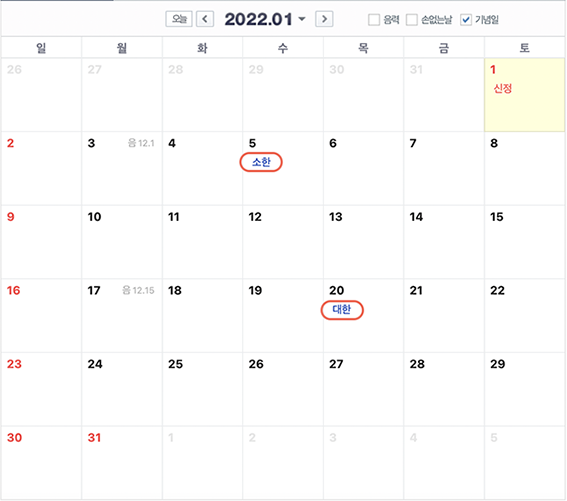

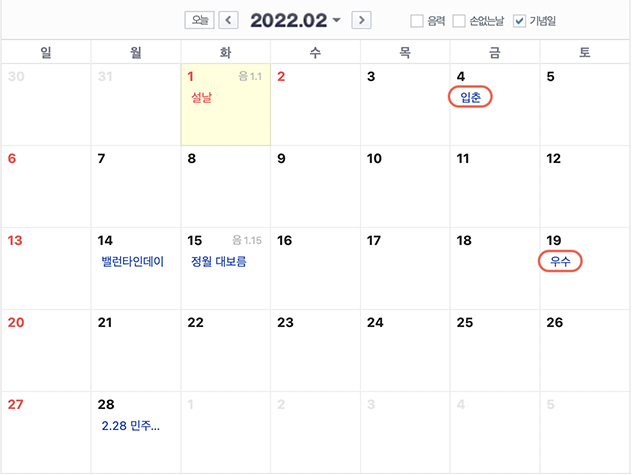

Whenever I observed them from March 15th to 30th, I recorded where they were and how they moved. Squares are the sketch of my ceiling, X is the mark for the spiders, and blue messages are my comments.

From observation day three till day 10, they didn’t move for a week; more accurately, I didn’t see them moving for a week. When I finally saw them moving slightly, I was excited and somehow relieved because I started making assumptions about why they weren’t moving; Are they dead? Are they dormant? Maybe they are nocturnal?

Observing becomes caring

Going into this explorative project, I hoped to understand their day-to-day lives and may be able to get a sense of time patterns. However, now I realize in-door spiders probably don’t need to be as active as the ones in nature and instead, I developed a personal (even tho it is very one directional) relationship with them. One week of unexpected inactiveness of spiders generated questions and created a space of curiosity and care due to the lack of intellectual knowledge that arachnologists would have; why do they live in my room? what do they eat? (I don’t think there’s much to eat here) How long do they live? And my questions started becoming a little more serious; what is their ecological role? what if they are the last spiders in Canada? How would it make me feel?

Spider time

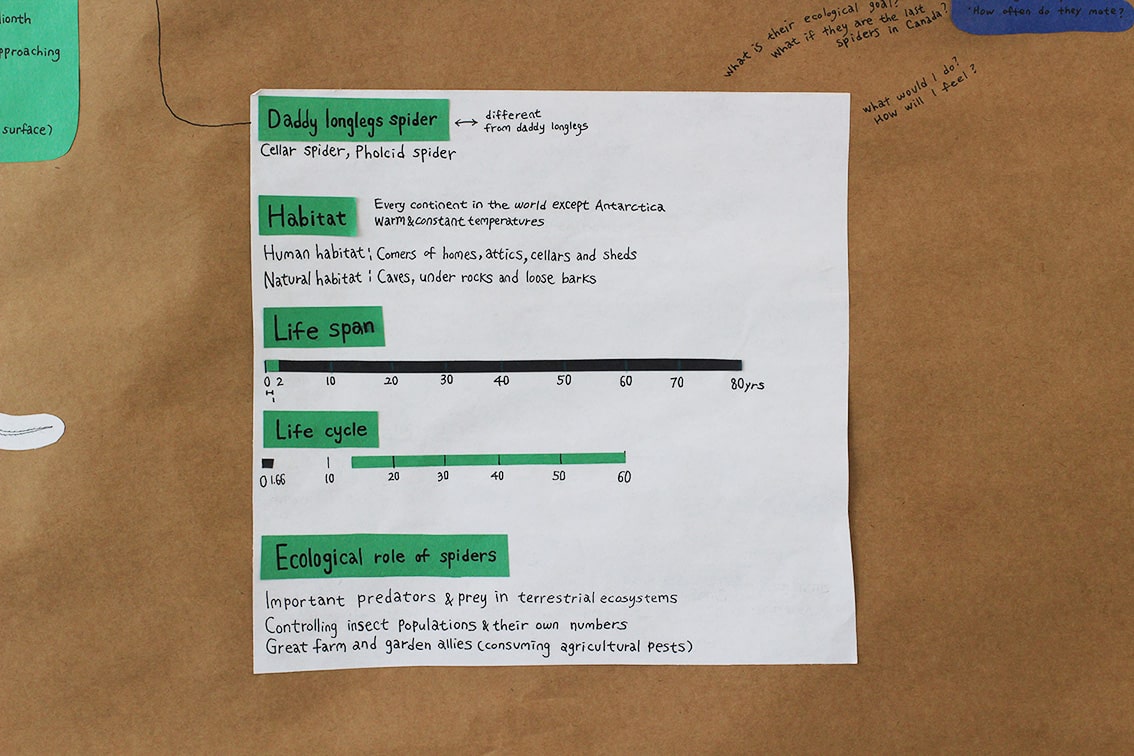

With the series of questions I developed in mind, I started researching cellar spiders and spiders in general to understand who they really are and whether some of my assumptions are true. (Ex. when I thought they were dead because they didn’t move for a week, I took a closer look and saw leftover spider legs on the web. Do they also eat other spiders and even the same species?-and the research answer is yes.)

Cellar spiders can live for about two years, and it takes one full year to reach their full maturity. And female cellar spiders produce about three eggs sacs over a lifetime, and each egg sac contains approximately 10-60 eggs.

According to The Conference Board of Canada, the average human life expectancy is 82 years in Canada. How many generations would cellar spiders repeat while we live 82 years on this planet? If I were born on the same date with a spiderling, I would die with the 41st one. What if our life expectancy was as short as theirs? Would it affect the way we live now? How would they experience time while we live the linear Euro-centric perception of time, past, present, future? Over 41 generations during 82 sun cycles around the Earth, would they be adapting to upcoming climate change and the plastic planet? Can I understand what nature is telling us as my ancestors could in the past?

Reflection

1. Avoid observing indoor non-humans.

“I want to observe urban non-humans I bump into everyday in Vancouver. Through observation, I hope to understand their day-to-day lives, life spans, and interesting features in a relationship with modern human time to bring their ecological roles visibly and hope to discover their hidden wisdom for us to learn.”

This was my intention for this project other-than-humans time in Vancouver trying to grasp their perceptions of time. From the spider time project, I learned I should avoid indoor non-humans since they live in artificial human habitats. If I were observing outdoor cellar spiders, I would’ve been able to pick up more patterns and rhythms.

2. Observing became caring-building a relationship.

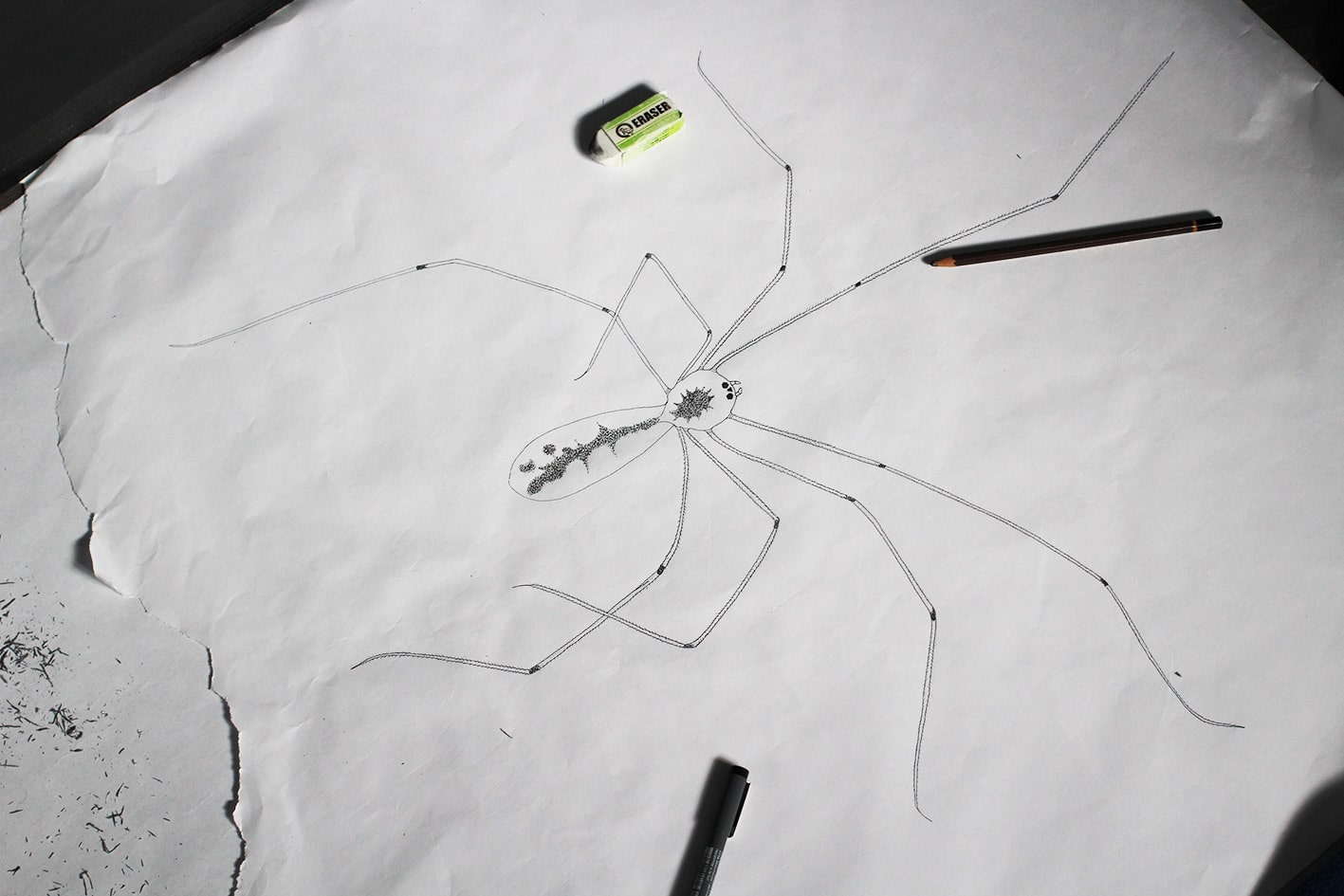

I started feeling attached to the spiders in my room that I only left alone because I couldn’t be bothered dealing with them. However, observing the same spiders for 15 days with the intention to understand their daily lives & patterns changed my attitude. Learning and discovering fascinating facts about them I now understand and respect their ecological role on Earth and feel very attached to spiders.

Spiders used to be one of the creepy insects I’d scream to my mom or dad to ask to catch. Now I see what they have that humans don’t have, how temporary they live compared to ourselves and how they are essential and complicated beings as a predator and prey to a lot of territorial ecosystems. Embodying this experience and seeing other peoples’ perceptions change, I also see a value in learning and sharing the knowledge about unfavoured, not appreciated non-humans that are commonly seen in urban environments, such as rats and silverfish.

3. plural versions of time

I visited Mon’s apartment the other day to watch crows commuting in her building. Organizing what time to meet was a hilarious experience since none of us didn’t know what time they would head back to their nests. Mon told me that as the sunset gets later, their commuting time has been getting later as well. (Aren’t these already fascinating factors to continue this project?) As she recommended, I arrived at her place around 530pm and we stayed on the rooftop until 730pm. Our attempt to watch crows commute didn’t work out that day, but it was an eye-opening experience imagining the speculative space of measuring time through different perspectives.

I want to continue observing other non-humans in Vancouver, but I’m wondering if there is a way to do it together with others. As my next observation, my candidates are crows, bees, geese and maybe cedar trees…